TIFF 2025: Day Eleven

Traveling on the TTC

I learned a lot about Toronto's subway system this year that I hadn't known. I've only been using the TTC for a handful of years as our hotels got further away from St. John and King (although I wish I used it back in the day when needing to travel between Scotiabank and Ryerson), so it's nice to discover its capabilities.

An almost disaster: Sunday trains don't start until 8:00am. If not for my travel companion still being in the hotel to snag an Uber ride with him, I probably would have missed my first screening. As it was I sat front row.

Trial and error: This was the first time I ever needed to switch trains. We stayed on Bloor Street last year too, but right near St. John to simply go north/south. This time we were so far down Bloor past Jarvis that I needed to also go east/west. I was surprised it was all included on the same ticket and tried two of the potential switches to find the best one. Piece of cake.

Unfortunate luck: And then there was me running onto a train assuming the doors were just about to close before finding out it was permanently stopped for a police matter (presumably above ground). I felt okay laughing as others did the same thing since I fell prey to that adrenaline rush of perfect timing too. So, I waited ten minutes to finally get going since I definitely wasn't walking instead.

Today's schedule:

• Aki, d. Darlene Naponse | TIFF Docs | Canada | Anishinaabemowin

• A Poet, d. Simón Mesa Soto | Special Presentations | Colombia, Germany, Sweden | Spanish

• Mama, d. Or Sinai | Centrepiece | Israel, Poland, Italy | Hebrew, Polish

Flana

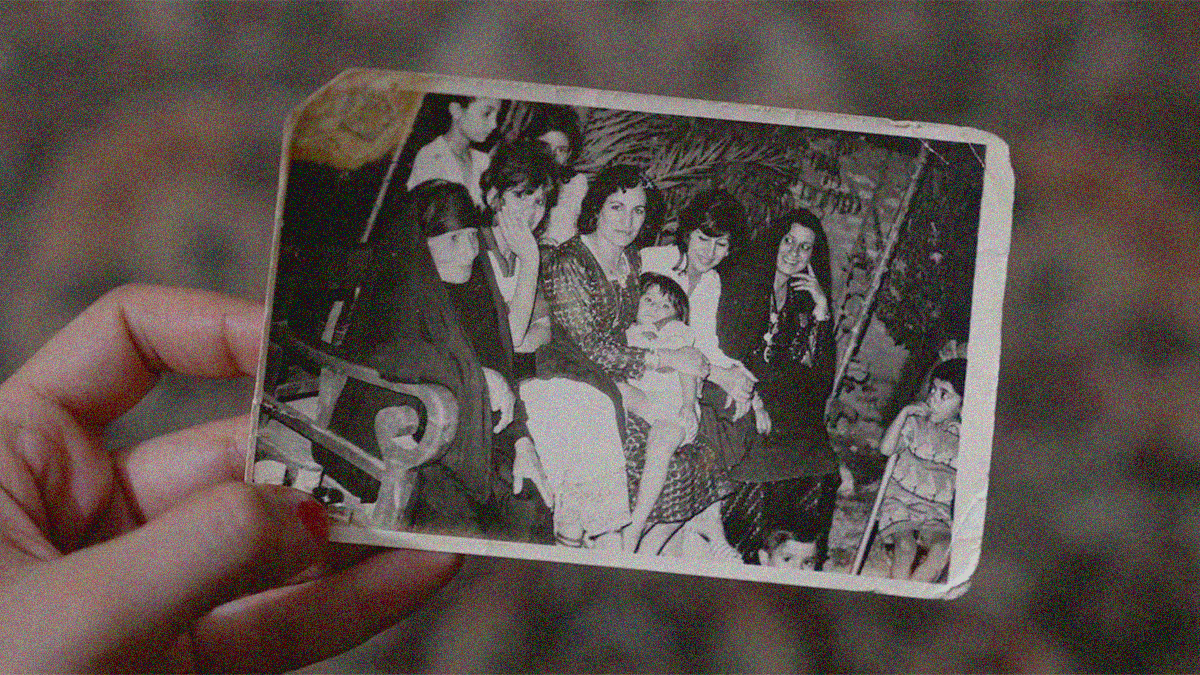

It begins as a search for a missing friend. Zahraa Ghandour remembers the day Nour was taken from her aunt Hayat Mohsen's home, but never fully understood why the event occurred there or where she was taken. They were both ten at the time, so context from whispers was difficult to parse. What proved most confusing, however, is that Nour's family remained living down the block. How could one person disappear without the rest? How could a family forsake their child and never look back?

As Zahraa grew older, the truth of a woman's plight in Iraq materialized as more than obscured sensory recollections like the birth of boys being met with celebration and the birth of girls earning nothing but silence. You start to learn about the graveyards of unknown women killed and discarded without recourse due to cultural permission and government condonation (if a woman's murder is committed by a male relative, it is deemed lawful). And then the shelters for orphaned girls that are operated as prisons.

Flana—the Iraqi word for those forgotten souls—unfolds as a letter from Zahraa to Nour about her journey towards these realizations. Her narration positions her old friend as her audience as though a plea to the cosmos for her spirit or body to listen and know someone still remembers. That someone still cares. Because Zahraa almost met a similar fate herself with a mother wondering whether to give birth during Operation Desert Storm considering she already had two other children. As it was, Zahraa spent most of her youth with Hayat.

We eventually discover what occurred that fateful day via Hayat's own memory, but there are still no answers for what happened next. Zahraa instead seeks to piece together what might have unfolded by visiting those shelters, combing through documents, and interviewing other women who survived a similar plight. That's where Layla/Natalie fits in. She too was ten when her father kicked her into the street, forcing her to choose between prison and an orphanage. Little did she know at the time that there wasn't really much difference.

Layla/Natalie tells her story as a surrogate Nour. Hayat remembers a time before the American wars when women were free to roam and be their own people. And we discover just how uncertain a baby girl's life proves upon birth amidst archaic notions of gender and honor. It's not necessarily anything new for those versed in the history of women's rights injustices in the Middle East, but there's purpose to hearing it all again considering the personal touch Zahraa brings to the project. It's therefore less of a lesson than a reckoning.

That intimate touch is both a boon and hindrance since it doesn't go deeper into these exposed realities beyond their anecdotal place in Zahraa's search. It's a fantastic in-road for the topic that audience members might think stops too short insofar as educating about the why, how, and what's next. That isn't Flana's goal, though. It seeks to remember and succeeds via the profundity of that act alone. So, your experience will vary depending on your documentary tastes since Zahraa does deliver on her promise. It just might not satisfy your expectations.

6/10

Oca

All roads lead to San Vicente—the place where the new archbishop (Raúl Briones) has inexplicably decided to make his home. Sister Rafaela (Natalia Solián), known for her prophetic dreams (ones her superior simply calls coincidences), dreamt recently of a confession with a man wearing a rose ring. Hearing that this new arrival uses that same rose as his symbol, she's sent on the arduous journey to ask his help to repair their crumbling convent. Rafaela doesn't know the way, but she has faith God will get her where she needs to go.

Congregates from a nearby town don't have that same certainty—not after the disappearance of their guide. They will still walk that same old road in hopes of reaching their destination, though, because they also need assistance. Unlike Rafaela, their actions force us to question their motives. First, the hypocrisy of two of their leaders damning young Rogelia's (Cristel Guadalupe) mother while engaging in similar sins. Second, their treatment of the girl when all she wants to do is help. Third, their deception of the Sister herself.

Writer/director Karla Badillo's biting morality tale Oca (named for a board game consisting of a path of pitfalls trying to wind your piece away from its final destination) isn't satisfied with these two parallel pilgrimages. There's also a paratrooper (Leonardo Ortizgris) on a personal mission that goes against his orders and an affluent woman (Cecilia Suárez's Palmira) being chauffeured (by Gerardo Trejoluna's Manuel) to meet someone at an airport. The question these characters face is whether they'll allow desire to take a backseat to charity.

That's the purpose of the road and why fate seems to have placed them all upon it simultaneously. Yes, the archbishop serves as a catalyst, but his position could be construed as destiny too—not his own, but that of the others. As Rafaela wonders about the wind changing the course of things through God's guiding hand, Badillo ultimately becomes that deity within the world of her film. She allows the Sister's motorcycle to break down and test the pilgrims. She conjures a storm to keep the paratrooper from deserting so he can eventually cross their path too.

Rafaela becomes a sort of lightning rod as a result. God's pawn presenting everyone else with a choice: exploit a stranger to satisfy you own goal or sacrifice that mission to help another. Let's just say a lot of F's will be handed down as grades because they pretty much all see Rafaela as their salvation regardless of what they must do to her to receive it. I'm not talking implicitly either. They explicitly objectify, guilt, and trick her. They treat their eagerness for her to serve them as her purpose. But her true purpose is to serve only God.

So, when they attempt to divert her from her path, she pushes back. When they sabotage her pursuit for their own, she sits and prays for guidance. Sometimes it arrives in the form of another lie. Sometimes it provides her a way forward (Palmira worries if she's a 'good person' only to prove she isn't time and time again until finally agreeing to drive Rafaela to her destination). What matters, however, is that she never gives up. That she endures the struggle and continues her mission unlike the others so quick to quit when their vision of success fails.

Oca truly is a depiction of that game with Badillo rolling the dice to send each piece in multiple directions so they all become lost under their own karmic weight. We get confused too as landmarks become repeated from opposite directions to truly turn this road into a black hole refusing to release anyone until the moment is right. And, even then, what they find for their trouble won't necessarily be what they imagined. Abandonment. Vanity. Fear. Death. As with everything else, though, it's still exactly where they should be.

It's a test of patience for Rafaela (Solián is great in the role, fiercely loyal to God and unafraid to subtly yet pointedly remind others when they betray themselves through their actions). Some audience members might say it's a test of patience for them too. I personally enjoyed the circuitous nature of the film, though, since there's narrative purpose to it. By putting everyone on an infinite loop of frustration, Badillo shows mankind's penchant for malcontent and treachery. It positions Rafaela as divine.

That's why I love the ending. Even those spinning their wheels should be satisfied by the turn of events transpiring upon Rafaela's arrival. While it may seem out-of-character or a product of madness, one must consider the fine line separating insanity from piety where "communing with God" is concerned. Because asking the archbishop for help was never Rafaela's purpose. That was merely what her Mother Superior demanded. Rafaela is guided only by God, and, as such, we must presume everything she does is His will. A game needs its victor.

7/10

Our Father

The men are stripped naked and yet their clothes still aren't spared from the vomit and excrement born from the brief period of withdrawal spanning their family member putting them in a car and their arrival at Father Branko's (Boris Isakovic) Serbian Orthodox monastery-backed rehabilitation center. His care is a last resort for many after the normal rehab centers haven't worked. Because these men are more or less put under Branko's full guardianship. To escape is to be arrested and sent back. To be freed takes years and his permission.

Rumors abound about the treatment within those walls, but the patients on the inside embrace the routine of hard work and determination because they feel their addiction wash away. Mionica (Goran Markovic) has been there three years already when Dejan (Vucic Perovic) shows up, so he's the perfect steward to get this newcomer up to speed. It's never fast enough, though. Everyone finds themself exposed to their drug of choice and an inability to relent. So, Branko bends them over a table and swings his shovel to drive home his point.

Dejan has his turn early in Goran Stankovic's Our Father. Someone new turns up and he's tasked with taking his clothes to the laundry. That's where he finds a foil wrap of heroin and instantly jumps into action to sneak it to the bathroom and inhale. Branko collects everyone in the dining room, hands the shovel to Mionica for failing to watch over his ward, and prefaces the ensuing violence with everyone's favorite hypocritical concession that it's "hurting me more than you." It's brutal. It's traumatizing. And ... it might just work.

Therein lies the complexity of corporal punishment. What seems effective in a very isolated environment could simply be a matter of site-specific conditioning. When one man rules autocratically with an iron fist, those in his care learn the elasticity of his violence and steer clear for the duration of their stay. This is Branko's method, and the pain is unforgettable. So, one plus one always equals two within the confines of this world. But what about the real world. Branko isn't your shadow out there. You might leave, but your fear of his wrath stays.

It's therefore easy to get caught in the moment. Three years without relapse for Mionica? Proof of success. The abuse hurting more than withdrawal? Addiction beat. This cause and effect thinking ultimately becomes a feedback loop, though, because the tactic's efficacy is only ever judged against itself. Add Branko's religious pontifications about giving his soul to save theirs and you buy into the propaganda. You victim blame yourself, agreeing you deserved it and there's no alternative. And you even fight to protect it.

This is where the "inspired by true events" portion comes in as Stankovic was captivated by an incident that occurred a decade ago in Serbia wherein a video of just such abuse was leaked to the media. It created a firestorm of debate that occurs regularly here in the United States considering we've given our entire carceral system to for-profit capitalists that yearn for a high recidivism rate to keep their shareholders happy. Some say these addicts need "tough love" to reform. Others explain how it's an unsustainable model built to fail the victim.

Our Father really leans into the coercion tactics necessary for the profiteering autocrat to keep power. I'm not even saying Branko doesn't truly want to help these men. He simply wants to preserve his outlet for wealth and sadism more. So, he starts doing favors for those positioned to save him, brainwashing them to reinforce the good he's accomplished through his bad acts. Those he harms end up being his most vocal cheerleaders. After all, Branko is the only person giving them respect. He's the only one who won't toss them aside and they owe him for it.

You can sense where it's all going due to the movement of certain pieces on the board, but the result is no less effective. This was always going to end in tragedy. Oppression either gets defeated from within or goes too far to continue being ignored by those on the outside. What hurts most, however, is the moment of awakening for these unwitting cogs in the machine. No longer must they only contend with their addiction. They must now also confront their complicity in their own oppression. They've never been so lost.

Isakovic is terrifying as Branko. As a priest he's a successful orator who knows just which buttons to press. A raised voice forces everyone to look at the ground and cower in anxiety while an outstretched hand is like Christmas morning. It's a character perfectly positioned to shed light on just how far ethnostate's go to absolve their terror by wielding it in God's name. Perovic, Markovic, and the other actors exude strength and vulnerability, but they'll always be puppets with invisible strings. Because real evil is making you believe you're the monster.

8/10

Pulled from the archives at cinematicfbombs.com.

Belfast screened on September 12, 2021 at TIFF.