TIFF 2025: Day Five

"That's the last Hooters joke."

Who knew the Toronto subway doesn't start running until 8am on Sundays?

Not me.

So, the day started in the front row for Gus Van Sant's Dead Man's Wire as the line-up was already huge upon my arrival. There was a mix-up outside the theater too where a staff member was radioing downstairs that the theater was full and everyone waiting to get scanned thought it meant they were being turned away. We weren't. We just had to watch the film with carnival mirror proportions.

Sacrifice was a chill experience except for the fact that I think I was the only one who liked it. And Good Fortune entertained on-screen and off thanks to writer/director/producer/star Aziz Ansari delivering a mini stand-up show riffing on the fact that Toronto still has a Hooters.

"They asked where I wanted my second screening held and I told them I wanted a theater on the same street as a Hooters."

"I haven't seen a Hooters in ten years. Why is that owl's eyes so big? Are the waitresses just really nice?"

Heckling two women leaving during the post-screening Q&A: "They had a reservation at Hooters."

Today's schedule:

• Normal, d. Ben Wheatley | Midnight Madness | USA, Canada | English, Japanese

• Karmadonna, d. Aleksandar Radivojević | Midnight Madness | Serbia | Serbian

Carolina Caroline

"Cue the road trip crash course in grifting and the electric chemistry of their tandem running amok with such expert precision that their crimes might somehow exude more sex appeal than their sex scenes."

Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

Dead Man's Wire

Tony Kiritsis (Bill Skarsgård) just wants respect. He doesn’t want to harm anyone who hasn’t harmed him. So, Barb the receptionist is fine. Heck, even Detective Michael Grable (Cary Elwes) is fine—they frequent the same bar and have had drinks together before. Tony knows half the police department by their first name for that matter. He’s a loquacious eccentric who simply gets along with people and maybe that’s why he’s in this situation. Because he trusted M.L. Hall (Al Pacino) and Meridian Mortgage to put his best interests first. He assumed everyone he knew was a stand-up guy who understood the common man’s plight. He was wrong.

The true-life events portrayed in director Gus Van Sant and writer Austin Kolodney’s Dead Man’s Wire are Tony’s attempt to get back what he’s owed (and should have earned). Sure, revenge proves a motivating factor too, but his main concern is receiving an apology wherein M.L. admits wrongdoing. Because Tony says he had deals lined up to develop the plot of land he used a Meridian loan to purchase, but they did nothing to facilitate. Not only that, but they also dragged their feet to the point where Tony was liable to default so they could offer him a garbage deal and take it off his hands. The little guy finally gains the upper hand on an investment and the big fish still finds a way to steal it.

It should be M.L. on the other end of Tony’s shotgun rig, but his son, and president of the company, Dick (Dacre Montgomery) will do just fine now that dad is vacationing in Florida. There’s no way Dick didn’t also know what was going on, so Tony doesn’t feel bad or think he’s taken an innocent hostage instead. He does feel for the man’s family, but this is what’s needed to expose their company for the crooks they are. When you hire someone to look after you, that is what you expect. You’re not supposed to be pushed aside for stockholders. You’re not supposed to be reminded that generational wealth is the only way for an American to succeed.

Is there credence to Tony’s claims? We want to assume the answer is yes, but this is an unhinged man. All we know for certain—and all the filmmakers truly need to provide for our investment—is that he believes this occurred. And since the rest is driven by that reality, we must also believe he will kill Dick if he doesn’t receive his demands. That his apartment is actually rigged to explode if anyone tries to gain access, but also that he will ensure his hostage remains unharmed if his terms are satisfied. Because this isn’t about celebrity or attention. It’s about justice. Those other things are fun, though. How else could Tony have been able to call Fred “the voice of Indianapolis” Temple (Colman Domingo) at home?

This beloved radio DJ is just another piece to what Grable affectionately calls a “shitshow” that spirals out of control from the start. Tony has the whole city at the barrel of his gun and dictates the terms throughout. So, when he’s tired of the police, he calls a man of the people like Fred to get his voice out into the streets. Citizens like him will understand his righteous anger. They’ll agree that he isn’t a deranged opportunist, but a bona fide folk hero. Is that why Fred complies? No. He wants to help save a man’s life. The media, though? They see dollar signs and career advancement. Linda Page (Myha’la) is riding this story to prime time and her boss prays he’ll get to air a murder on live television.

Tony Kiritsis’ story is a wild one and this period piece does it justice as an historical curio with immense entertainment value from hindsight. Skarsgård is having an absolute blast in the role, effortlessly sliding between honest empathy and temperamental impatience with each changing development outside his window. And there’s a nice rapport with Montgomery too—one teasing a Come-to-Jesus moment insofar as complicity is concerned that’s ultimately helped by a brief Pacino showcase to reveal M.L. is the remorseless bastard Tony says he is. Does that thaw ever occur? Not really. That’s the trouble with true stories sometimes. The most intriguing potential for complexity within them must be ignored for veracity’s sake.

Dead Man’s Wire is solid, nonetheless. Van Sant infuses it with an energetic air of farce that flirts with the inherent satirical messaging within such indelible moments that transcend reason to become part of the zeitgeist. The sheer logistics of Tony crafting all these contraptions to hold the police at bay and ensure his own safety from a sniper’s bullet is enough to prove how singular an event this was in 1976. The confusion from thinking it was a robbery only to watch perpetrator and victim walk down the block to change venues provides so much chaos that anything can happen and be easily recorded without strict barriers from public consumption. It truly feels like a precursor to reality television.

7/10

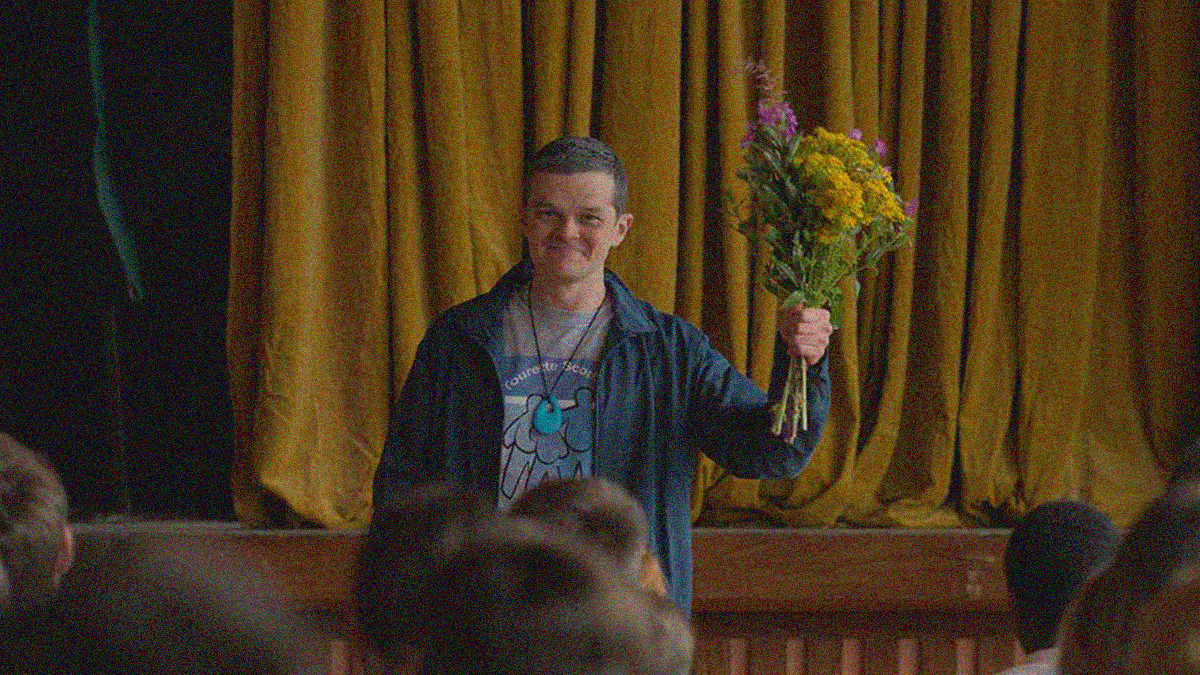

I Swear

The opening to Kirk Jones' I Swear is the perfect entry point into John Davidson's (Robert Aramayo) life. The year is 2019 and he's about to receive his MBE from the Queen for services helping to increase the understanding of Tourette syndrome. Standing outside the ceremony room, he argues with Dottie Achenbach (Maxine Peake) about not wanting to go in—scared of what he might do or say as a result of the mounting anxiety. After finally cajoling him, they're just about to sit when "F*ck the Queen!" comes bellowing out of his mouth.

That's when we rewind to find John (Scott Ellis Watson) as a teen soccer goalie turning enough heads to warrant a scout visit in the 1980s. Couple the pressure of that opportunity with beginning his first year of high school and the stress would get to anyone. Unfortunately for John, however, it ultimately exacerbates what was surely already peeking out. First, it's the tics. Then it's the outbursts. And finally, it's a complete inability to control himself from spitting food into his mother's face. Soccer becomes impossible. Bullying becomes rampant. It would have been odd if he didn't battle suicidal thoughts.

Fast-forward thirteen years and things are much the same with Mom (Shirley Henderson's Heather) still talking like he should be "strong enough" to control himself in public. Enter Dottie—a woman we assumed was his mother during that opening scene only to be confused when she's absent throughout his childhood. She arrives to the story as the compassionate mother of a friend. A nurse, like Heather, Dottie spent her career in mental hospitals and therefore understands conditions like Tourette's more than most considering it wasn't yet considered "real." Heather chose medication as a treatment. Dottie suggests empathy.

Suddenly everything changes due to an act of kindness as simple as telling John he mustn't apologize for actions he cannot prevent. Acceptance is often the most powerful drug any can hope to receive and it supplies this grown man conditioned to fear the outside world a modicum of freedom ... from himself. He can swear at Dottie. He can smack her in the face when she accidentally stands on his right side exactly when his body unleashes an involuntary punch. He can exist without wondering whether someone will beat him up or if his mother's fatigue will fashion her face into another frown.

John's life progresses with a ton of new highs upon meeting Dottie, but that doesn't mean there aren't even more lows. This is an era of ignorance, after all. The level of intolerance today is astounding, so just think what it was like in the 80s and 90s. Between hotheaded brutes and hotheaded cops, the hospital visits and court dates are unavoidable for a man whose brain forces him to blurt out the very thing they need to want to rough him up or throw him in jail. As his mentor Tommy Trotter (Peter Mullan) often says, Tourette's isn't the problem. It's a lack of education.

Well, considering that opening prologue, we can guess he takes those words to heart to position himself at the forefront of a movement to teach, train, and support fellow sufferers, their overwhelmed parents, and the community at-large. The film makes it seem like an epiphany type scenario, but the real John Davidson was actually quite well-versed in the potential of being a role model (or test subject depending on outsider motivations) considering he was the subject of a 1989 documentary titled John's Not Mad and other BBC follow-ups.

Regardless, it's these steps as an adult that resonate—especially considering all the suffering we've witnessed on-screen (both tragic and, often, comical). It's that empowering message that propels John's story forward and makes good on the promise Dottie provided by allowing him the space to find a voice beneath the one he was reduced to by his affliction. So, get the tissues ready as there will be plenty of opportunity to shed tears thanks to Tommy's stirring encouragement, Heather's inevitable forgiveness (for herself), and John's own recognition of just how far he's come.

To that end, despite Henderson, Mullan, and Peake earning high praise for their authentically nuanced performances around him, you must applaud Aramayo's vulnerability in bringing John Davidson's story to life. Because it never feels like a caricature. Behind every outburst—whether written for tension or an intentional laugh—lies a prevalent sense of contrition and, sadly, fear. The former is where we witness John's infectious personality (no one who ever truly gets to know him doesn't love him) while the latter reveals his constant struggle to find the confidence and safety necessary to live.

It's a delicate subject handled with great sensitivity, humor, and intelligence by Jones. One could probably dismiss it as by-the-numbers insofar as how it unfolds as a message-driven biopic, but that's a lazy read on what's an effective use of the formula that actually proves why it's used so often. Credit Davidson too considering he serves as an executive producer. The life he's survived surely cultivated a thick skin so his activist work could achieve the level of honesty necessary for a warts-and-all dramatization. Bringing this film into the world only helps expand the reach of his quest to educate, inspire, and protect.

8/10

Mārama

I'm unsure how you could read the genre description of Taratoa Stappard's Mārama as a "Māori gothic horror set in Victorian England" and not find yourself racing to be seated. Add an image of Ariana Osborne's Mary in a giant red dress with gigot sleeves while engaged in an impassioned haka and the potential for the film to truly dig into the historical colonial violence that occurred in what's now known as New Zealand comes into full focus. Because this woman has most assuredly been grievously harmed by British occupiers. Whether directly or not, generational trauma grabs hold to the bones without ever letting go.

We meet Mary as she's being unceremoniously thrown out of a horse-drawn carriage by its racist driver and pointed down a steep hillside towards her destination. She's meant to meet a British man who claims to know about her ancestors—a topic for which she has zero recollection having been adopted and raised by an English family. All that's inside his sparse home is a bare bed and a mirror on the wall. When Mary's candlelight hits that glass, though, we see the ghost of a man on its mattress. Is it her imagination? A vision? Perhaps an echo of past horrors soon to be repeated?

Think of it as an "all-the-above" once Mary makes her way to Sir Nathaniel Cole's (Toby Stephens) palatial Hawkser Manor. Friends with the gentleman she was to meet, he felt it his duty to send for her upon discovering she'd arrived. Cole spent years in New Zealand himself and explains his profound respect for the Māori—even revealing his fluency with the language. His hospitality isn't merely a courtesy to shield her from the elements of that drafty room, though. No, his hope is for Mary to accept his offer of utilizing her teaching expertise to become his nine-year-old granddaughter Anne's (Evelyn Towersey) new governess.

He's not wrong when he says she'll have a tough time finding a job this good elsewhere in England, but the presumption definitely gives Mary pause. So too do the series of new visions that occur whenever she gazes upon her reflection or touches someone within the estate. The imagery is always brutally horrific. Always someone dying by strangulation or a gunshot if not just screaming into her face. Having never seen New Zealand herself, we're unsure what these moments are or the identity of victims and perpetrators alike. Is each act a piece of her history? Cole's and Anne's Uncle Jack's (Erroll Shand) history? Their shared history?

The ramifications of it being the latter prove the most potent since this whole situation is too convenient and purposeful for it to be a coincidence. And since Stappard's desire to craft a film with these connections to the past was partly to reckon with his own Māori ancestry, we know the forthcoming discoveries will be difficult to absorb. This is why he begins everything by putting his cards on the table as far as Mārama's content is concerned. He will pull no punches to expose the "violation and desecration of Māori culture" in Aotearoa because the only way to move forward is to understand the inherent trauma you carry.

At just under ninety-minutes, Stappard and Mary waste little time investigating her fainting spells, legacy as a "seer," and Cole's true purpose for wanting her to stay. She instantly recognizes his admiration for the Māori as a remnant of his need for conquest and ownership. He wields this interest as a manipulation rather than compassion because he's too comfortable in his position of power over her to truly believe she could ever pose a threat. Even when his Captain James Cook-themed birthday celebration of brown-faced inebriation is interrupted by Mary's haka's intense display of spiritual intimidation, Cole believes he's in control.

Theirs are two unforgettable performances as a result. Desperation versus hubris. Identity versus appropriation. Stephens is as charismatic as ever, toeing the violent line he knows exists between them so as not to scare her off immediately yet never worried when she proves he's crossed it anyway. And Osborne is a tour de force of emotional upheaval as her very presence in the lion's den reveals every nightmarish detail about who she is and who her ancestors now need her to be. Their third act is a bloody and bold bid at reclamation. More than one woman's vengeance, Mary is a symbol of familial, cultural, and indigenous retribution.

8/10

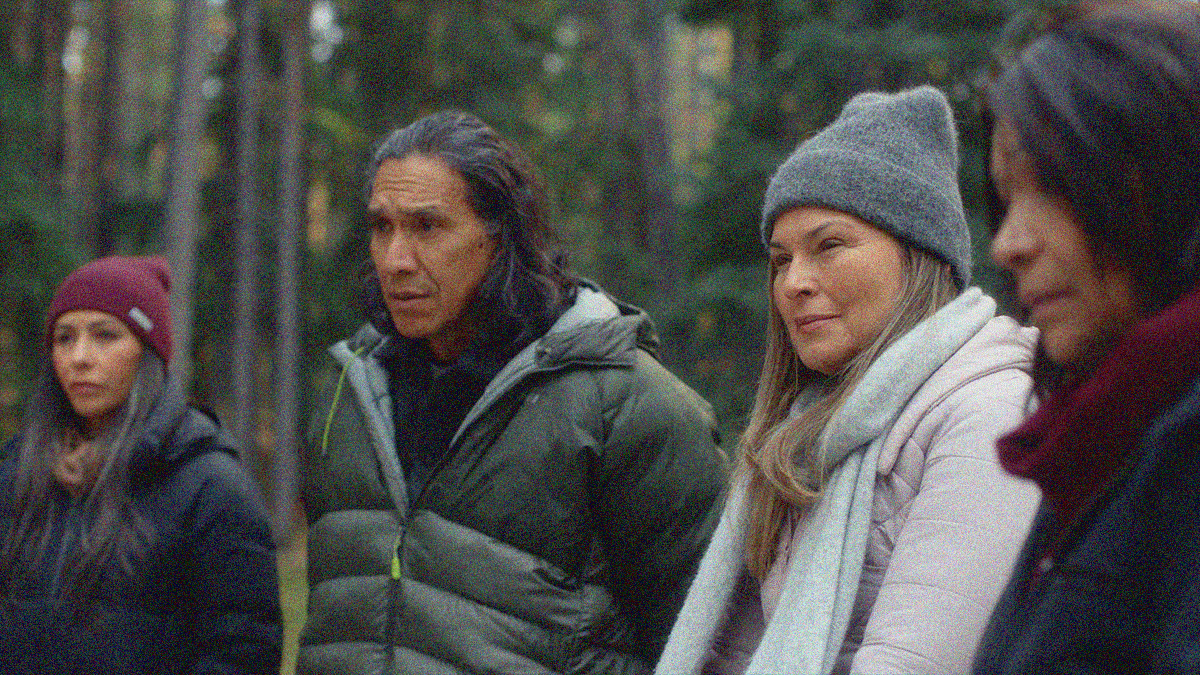

Meadowlarks

The general assumption is that indigenous actors are mostly offered stereotypical roles within white-led productions. And like with so many minorities, those filmmakers often demand a one-dimensional caricature of their race rather than a three-dimensional projection of their authentic selves. So, of course, Tasha Hubbard's fictional narrative debut Meadowlarks (inspired by her documentary Birth of a Family) would cause its cast pause and process its undertaking within that context. Here's a film produced and directed by indigenous artists and they're being asked to play characters fully disconnected from their culture.

It's ironic in the bigger picture sense of the film industry, but crucial to the story Hubbard and co-writer Emil Sher have crafted since the reason for that disconnect is a traumatic one only indigenous North Americans could fully understand. Because neither Anthony (Michael Greyeyes), Gwen (Michelle Thrush), Marianne (Alex Rice), nor Connie (Carmen Moore) chose to forsake their heritage. This isn't an immigrant tale about assimilation and homogenization. No, these four siblings were torn from their home and forced to experience the loneliness, shame, and rage conjured from being victim of the "Sixties Scoop."

Here they are forty some years later and it's as though they're meeting for the first time since most of them were too young to remember life before social workers picked them up and shipped them off. You can't therefore call Marianne "lucky" for having been placed with a loving family in Antwerp because a great new life doesn't erase the void left from never knowing the life stolen from her. The same goes for Connie considering comfort with a white family still meant ridicule from her adoptive brothers and the constant threat of wondering if one mistake might mean having to leave them too.

Their only luck was having been young enough at the point of their extraction to still be wanted. Because Anthony and Gwen weren't. They were bounced around foster homes. They were traumatized again and again by the government, the Canadian populace, and their own feelings of inadequacy born from this cycle of rejection. And even they might not have endured the worst of it. No, their older brother George refuses to take part in this reunion at all (a word they question considering it means they've been united previously). We're talking about deep emotional scars that one weekend cannot wash away.

What it can provide, however, is a start by opening a path towards healing. It won't be easy since they're all at differing stages of coping with what happened and reconciling their fractured identities (Marianne's athletic success allowed her to fully embrace being Belgian, Connie was always told a desire to learn about her roots would destroy her adoptive parents, Anthony's discovery that he's going to be a grandfather puts him into overdrive as far as returning to that part of him that provided so much pain, and Gwen still can't quite articulate what she survived), but who better to trust than each other?

The script does a wonderful job balancing the routine small talk of sharing life stories and the debilitating and often unspeakable suffering they've either kept bottled inside or didn't even know existed until right now. I won't deny that things can get overly schmaltzy when this foursome overcompensates for lost time, but that's merely a byproduct of their wounds being so devastating. We need that over-the-top, tearful pouting to shake us from the gut-punch of emotion dealt whenever one of them reveals a new dark truth or sheepishly admits to wanting to know more about who they are without really knowing where to start.

Because the damage is permanent and its modes of delivery infinite. The sheer act of being taken. The cruelty of being othered in a setting they've been forced to reside within. The hypocrisy of a government that saw them as property to be given away without a second thought about the ramifications. The reality that their pain would ultimately be passed down to their own children. The sense that they don't belong in the one place they should despite still not belonging in the only place they've known. It all pours out via music, photos, personality quirks, and heartfelt admissions over phones, to each other, and to themselves.

And then there's also a kindly older couple on the reservation outside of the tourist trap that is their Banff, Alberta getaway. Alma (Theda Newbreast) and Simon (Russell Badger) become critical pieces to this puzzle by becoming an extension of what this weekend represents insofar as inclusion, acceptance, and understanding. Because it's one thing to find family through marriage and another to reclaim family through blood. But there's still that lingering question about rediscovering community with their ancestors. It's no small thing when this couple invites them into their circle to assure them that they do belong.

That's when the floodgates truly open. When all the things they've still been too embarrassed to admit comes out. So, don't think yourself strong or Meadowlarks tame because you didn't feel the full force of the love and anguish onscreen before then. There are more horrors left to endure as the full breadth of the "Sixties Scoop" (an estimated 25,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit infants and children displaced by child welfare authorities over thirty-plus years) comes into focus. But there's also a lot more healing as these siblings recognize they mustn't confront their nightmares alone anymore.

8/10

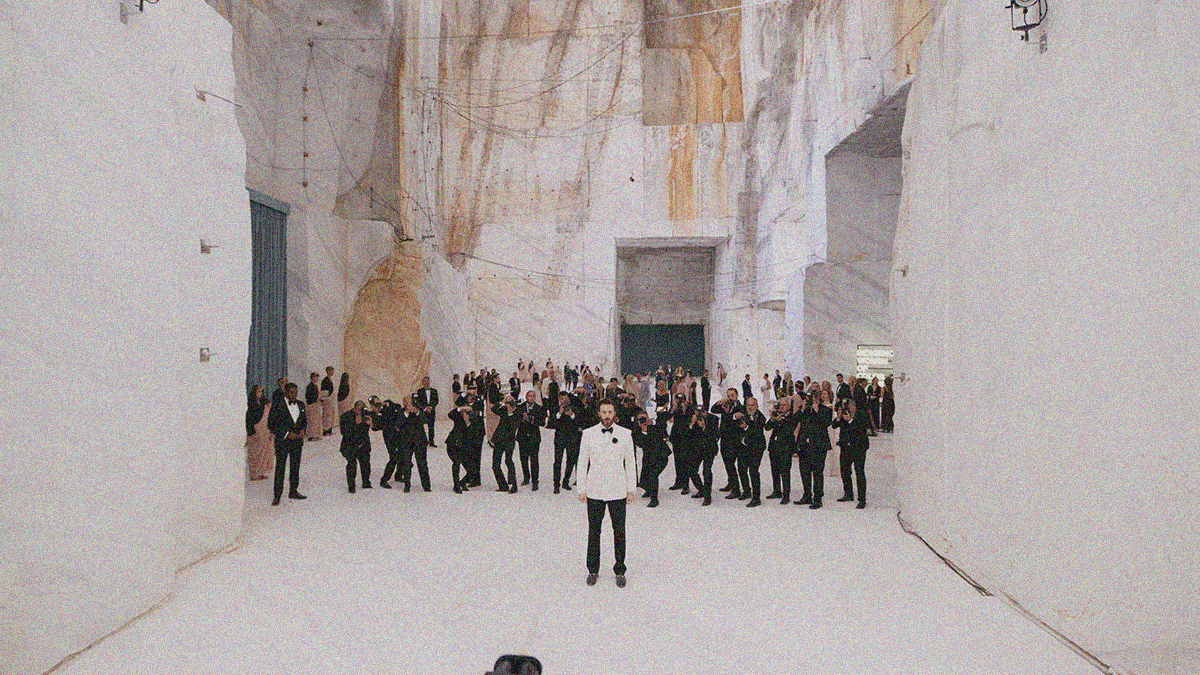

Sacrifice

The only thing better than finding a real hero to save the world is a narcissist. The former is still human and can have a change of heart. They can get scared or perhaps die heroically participating in another life-or-death scenario before the original task assigned to them. A narcissist, though? They would never in a million years consider anything close to heroism. They’ll merely fantasize about it because the potential spoils and celebrity that come with fulfilling such an obligation are something they would crave. If that delusion spirals out of control, however, they might trick themselves into doing it anyway.

This is the difference between conviction and vanity. Joan (Anya Taylor-Joy) has lived her entire life believing in her calling as steward of the “fire.” She has been indoctrinated by her family’s cult to hear the voice of a cataclysmic volcano describe its need to be satisfied by the cleansing power of death. Mike Tyler (Chris Evans), on the other hand, doesn’t even have faith in himself. A famous actor whose superficial confidence gets shattered by the loss of his father, he suddenly doesn’t know who he is let alone what he wants. So, to suddenly be given the chance to possess real purpose—no matter how insane—can’t help but be appealing.

These are the two forces pushing director Romain Gavras and co-writer Will Arbery’s Sacrifice towards its literal leap of faith. Set inside a Greek island’s marble mine at a charity event of one-percenters patting each other on the backs for profiting off their so-called altruistic desire to save the planet from mankind’s destructive might (led by a man who believes himself a God who’s discovered a way to cure global warming by pillaging the ocean floor instead as though that won’t have its own uniquely horrible impact), a radical fringe group led by Joan decides to take hostages and martyr three fated souls to Mother Nature’s wrath.

It’s youthful vigor versus experienced apathy. Impoverished yet dedicated soldiers who live only for the preservation of Earth versus the morbidly wealthy elite who care only about greed. Action versus performance—something even Mike recognizes despite his complicity to the side of evil. Unfortunately, seeing isn’t enough if your response to their ego trip is to simply conduct your own. All his theatrical outburst earns is a reprieve from witnessing Joan’s brethren’s arrival while hiding in the bathroom to wallow in his own obsolescence. And by not experiencing that violence, he has no way of knowing the applause upon his return signals his demise.

Evans is perfectly cast as the vain rube who unwittingly walks himself to the edge of true clarity. Mike is a self-made joke whose insecurities squandered whatever good will he found through his career and rendered him a meme to be laughed at and ignored. The vapidness of his existence and the filter from which he sees the world (helped by his agent, played by Sam Richardson) is about clout and branding. So much so that the idea of becoming a hero isn’t the initial draw to going along with his place in Joan’s plan. No, he just sees it as a chance for exposure. One more attempt to launch a new and improved Mike Tyler.

Because that’s all any of us are. Stories. Our pasts dictate our present, but we are ultimately the ones preserving and/or fabricating the former so that the latter proves as comfortable and successful as possible. Joan is no exception. She’s taken the warped gospel as taught by her father (John Malkovich’s Magnus) and built her entire personality around it as all zealots do. Choosing the Hero, just as her siblings must choose the King and the True Love, becomes her identity. The difference is that Mike knows his story is false so his vulnerability and fear can chip away at its permanence. Joan has never considered hers to be anything but true.

Their parallel journeys are therefore as much about a mission to prevent the apocalypse as using each other as a mirror to find truth within themselves. Sacrifice is an over-the-top satire full of laugh-out-loud sight gags (“Make Earth Cool Again”) and dialogue, but there’s also a lot of truth behind the humor. I think Gavras has one-upped reigning cinematic satirist Ruben Östlund with this task because he has his finger on the pulse of the counterculture whereas The Square and Triangle of Sadness seem to simply skewer the establishment with establishment art. Everything Gavras makes feels dangerous by comparison.

That fact is paramount here because its mythological endgame possesses zero wiggle room. If Joan has her way, three people (or more) will be dead to save everyone else. Her God complex is therefore almost as large as Vincent Cassel’s Braken—the billionaire who believes nature exists for mankind to dominate. She’s so devout to this scripture that she’s willing to kill herself to see it through. And that’s the part that most impacts Mike. Joan’s integrity is something he can only imagine. Something he can only conjure by psyching himself up for a role. That’s how he treats this whole ordeal. “Learn their language,” he says. Understand your audience.

I know I’m describing the movie’s weightier ambitions when its comedic tone will be its selling point, but that’s why Gavras and Arbery’s script is so good. They can shoehorn in a Malkovich cameo full of absurdity that in turn renders even more of what’s already known absurd and still have it become the linchpin of the whole film. Because it’s not Joan’s zealotry that inspires Mike. Nor her words of encouragement towards him. It’s her realization that her entire life might be based upon a lie and her ability to shake that doubt to stay the course anyway. Maybe it will all be for naught, but she’s come this far. Why lose faith now?

8/10

To the Victory!

Give Valentyn Vasyanovych a bigger budget and you can be sure The Clash's "Should I Stay or Should I Go" would be playing at some point. Because that's the question faced by the characters on-screen in this fictional post-war Ukraine. As we hear on the radio in Valyk's (Vasyanovych) kitchen, the country's population has been reduced to thirty million with twelve million now displaced throughout the world in exile. So, should the mostly women and children uproot the new lives they've created and return? Should the men who stayed go to them now that their nation is secure (depleting the census more)? Or do both sides start anew?

The film's title To the Victory! isn't therefore as joyous as you might initially assume since said victory demands complex conversations in the aftermath of decreased adrenaline and emotion. Valyk stayed because he believes in Ukraine and wants his filmmaking to be part of its rebirth. That doesn't mean his wife disagrees—she would never have considered leaving if not for Russia's invasion forcing it. But the world has changed and they've lived through wholly different experiences apart in the process. Add kids to the equation (especially when they are also separated) and the concept of a "correct" answer becomes obsolete.

All Valyk can do is continue making movies. And without the familiar infrastructure necessary to do so (like with Vasyanovych's own name-dropped Atlantis blurring the line between fact and fiction further), he must do so with his friends. What we're watching is simultaneously that film as well as the film about making that film. It's why some descriptions call To the Victory! a documentary despite doing so proving, at best, a stretch. Yes, it's autobiographical considering the topics he broaches are topics everyone on-screen will face in the aftermath of a ceasefire, but there's definitely a layer of remove.

If I were to equate it to a non-fiction sub-genre I'd say it's a speculative essay film. Its script and fourth wall-breaking conventions provide Vasyanovych a forum with which to grapple with his reality and find catharsis. The potentially looming divorce from his wife Sofia (Marianna Novikova). His best friend and lead actor Vlad (Vladlen Odudenko) considering choosing his family and moving to Spain. His son Yaryk (Hryhoriy Naumov) embedding himself in Ukraine to set down his own roots and begin his adult life. His aging father still visiting the cemetery to never be too far from his late mother, wife, and relatives.

Those cemetery scenes linger because they really drive home what it means to say goodbye. You aren't just losing your homes or careers. You're losing your heritage. That will ultimately mean different things to different people, but it doesn't lessen the blow. Sofia should take her daughter into consideration since one could argue her age makes it so she's lived more of her formidable years abroad than in Ukraine. So, at a certain point, the setting of her exile becomes the home she'd be leaving. Don't begrudge Valyk for wanting to stay anyway, though. Sofia won't. These are impossible decisions in unprecedented times.

It's not all doom and gloom, though, as Vasyanovych captures the camaraderie that has sustained their nation against the aggression of a world power such as Russia thus far. A party scene of Yaryk celebrating his first paycheck is a ton of fun. Valyk jokingly figuring out how to make his somber film about separated families "sexy" is hilariously brought to life via their frustrations towards reality ... and the assistance of alcohol. And even some of the pain finds a laugh or too like when Yaryk crashes his electric unicycle so that Valyk must carry him piggyback all the way to the hospital.

Would it have been more coherent and perhaps potent without all the shifts in perspective? Probably. The uncertainty of whether the latest static camera set-up is diegetic or not is initially exciting, but it also distracts upon losing its mystique. It still creates some incredible moments (the kite scene), but I'm unsure if it adds enough to not wonder whether they'd land just as well without. Because the real emotion comes from the conversations. Every time Valyk and Vlad are together. Yaryk's resentment and appreciation of his father. Valyk and Sofia's goodbye. The more authentic the set-up, the more profound—no camera tricks needed.

6/10

Whitetail

It's impossible to move forward if you've never confronted that which you hope to move on from. So, no matter how much Daniel (Andrew Bennett) wishes for his daughter to restart her life after decades of stagnation stemming from a traumatic incident in her youth, pleading with her isn't going to be enough. Jen (Natasha O'Keeffe) knows this. It's why she's stayed in their sleepy Irish town to make penance both by working as a rewilding conservationist and by refusing to let go of her suffering. And, in that respect, Oscar (Aaron McCusker) knows it too. It's why he did leave hoping to escape the pain. But it never went away.

Our entry point into Whitetail is a prologue showing us what happened that fateful day. Writer/director Nanouk Leopold wants us to understand the connection shared between Jen and Oscar before tragedy strikes so we can better comprehend their dynamic afterwards too. Because the real meat of the film begins after we fast-forward to the present and learn about his return. The news stops Jen in her tracks before she can catch herself to pretend like it doesn't matter. If you somehow believe this ruse, she will soon fully let the stoic façade slip upon finally seeing him and promptly turning right back around.

His presence brings her back to that day—not that she ever forgot it. No, Jen was simply able to put up her defenses and cope as long as the people around her allowed it. But Oscar? She can't look at or think about him without dredging up the pain. He is inextricably tethered to that event and, unhealthy or not, his prolonged absence helped hold those feelings at bay. So, of course the nightmares would restart. Of course her actions would grow more unstable as everyone asks if she's spoken to him yet. Oscar is a harbinger of death to Jen now. In her mind, the only chance to stem the darkness is for him to leave.

What we're shown is therefore her gradual acceptance of reality insofar as no longer being able to fool herself that everything is fine. We learn about failed relationships (Rory Nolan's Bobby), unwanted flirtations (Aidan O'Hare's Liam), her father's wish to sell their land and meet his new girlfriend (Hélène Patarot's Pei), and the poacher roaming the preserve at night and leaving decapitated deer carcasses in sections where hunting is illegal. Add Mona's (Simone Kirby) doting to turn her into a bridesmaid and it's as if the walls Jen built around her are closing in. Her stubborn rejection of dealing with any of it is suffocating.

All the earmarks of avoidance are present from Jen doubling down in her work to catch this rogue hunter to her chasing vices (a random hookup outside of town) to hopefully quell the nightmares. But the dreams don't stop. Images of her father buried in the dirt with the insects she has saved through her conservationism crawling atop him. It's always nature permeating her subconscious because it's nature that she most closely connects to what happened. That's where it occurred. That's what she's devoted her life to protecting. Every new hunter personifies the callous destruction she combats. The destruction she wrought in youth.

O'Keeffe delivers an unforgettable performance in the lead role, wearing her character's anguish throughout whether via explosive rage that must be released if she's unable to flee the source of sensory overload or the quiet sorrow of mini panic attacks she cannot control. We recognize the fear behind that anger too—especially when targeted at Oscar considering he's finally come to terms with the fact that their shared wound has remained open this entire time. Because she's not afraid of him. Not really. He's simply a mirror of grief she can't bear to peer into because it will reveal everything she's been hiding from.

Some might knock Whitetail for its climax circling back to its beginning, but I'd hardly call the act a convenient narrative bowtie. Yes, it's a bit heavy-handed, but it's also the perfect path out of the emotional echo chamber Jen has imprisoned herself within. What better way to finally allow herself to be vulnerable than to step into the opposite shoes from those she wore previously? Leopold has been effectively coaxing her towards it with a series of release valves. Oscar. Her father. The trees themselves. Little by little she's finally begun to reclaim her soul as penance makes way for peace.

8/10

Pulled from the archives at cinematicfbombs.com.

Knives Out screened on September 7, 2019 at TIFF.