TIFF 2025: Day Six

Home sweet home

That's a wrap on my in-person portion of the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. King Street is once again open to traffic, the hustle and bustle has died down considerably, and the world keeps turning.

My final film was the entertaining if familiar Normal and the best line of the weekend came courtesy of the long-time TIFF manager manning the Scotiabank Theatre chaos while waiting to get in. It was about 7:55am and the roped line for Hamnet was already full with an extension heading around the corner onto John Street. More and more press and industry people were filling up the sidewalk awaiting the 8:00am door opening.

"If you're here for Hamnet, get your butts to wherever the hell the end of the line is and hope. Cinema One will be lining up here outside once they're all gone. The rest of you can go upstairs."

Today's schedule:

• The Tale of Silyan, d. Tamara Kotevska | TIFF Docs | North Macedonia | Macedonian

• Under the Same Sun, d. Ulises Porra | Centrepiece | Dominican Republic, Spain | Spanish, Mandarin, French

Forastera

It starts as a gag. Pepa (Núria Prims) rings to apologize to her mother and believes it is she who picks up the phone. Her teenage daughter Cata (Zoe Stein) plays along, pretending to answer as she assumes her grandmother would until her mother finally catches on and says her name. When it happens again, however, Catalina (Marta Angelat) has died. But instead of telling the hairdresser this news, Cata once again pretends to be her grandmother to cancel the appointment and assure the woman that she'll ring soon for a touch up.

Why? Because Cata isn't ready to let her grandmother go. The two were very close thanks to summers spent at her beach house in Mallorca. They share the same name and people constantly tell her how much they look alike. It's such a problem that Pepa requests she not wear any of Catalina's clothes around the property just in case her grandfather (Lluís Homar's Tomeu) sees her. He's taking this tragedy very hard—talking about how her spirit remains. Catching a glimpse of Cata in one of his wife's dresses might just confuse him more.

What Pepa doesn't realize, though, is that Cata needs that confusion to prevent herself from having to deal with reality. She's the one who found her grandmother face down on the stone stairs. She's the one enduring a PTSD episode when seeing a drunk co-ed lying on the sand. If Cata can trick her grandfather into acting as though she is Catalina, then the rest of this summer can continue like normal. There's even a sense of healing in the make-believe as far as finally getting Tomeu out of the house, but one of them must eventually wake-up.

Lucía Aleñar Iglesias' Forastera follows Cata wading through this new reality amidst the backdrop of what had been a consequence free vacation with Swedish tourist Max (Nonni Ardal Hammarström) and her usual antics with her grandparents. Suddenly grandma is gone. Mom has arrived. And the arguments and emotions she and her younger sister Eva used to ignore become so unbearable that Cata starts playing matriarch just to stay sane. She's correct in many instances too—enough that her elders stop demanding she watch her tone.

Because it's hard on them all. None of them quite understand what they should feel since they are often too busy worrying about how everyone else feels. Tomeu wants to sulk in the present day's malaise. Pepa wants to take control and make plans for the future. And Cata hopes to stop time and return to the past. Tensions rise as a result of these contrasts and they each begin to resent the other's perspective rather than sit down and listen. If this family has a singular genetic trait, it would be stubbornness.

What makes the drama truly captivating, though, is that Cata's need to allow herself to be possessed by her grandmother's spirit isn't solely driven by intent. Yes, she puts herself into situations that would make any mother worry about boundaries with a grieving man, but there is both a sweetness to many moments and an inability to prevent them. Cata doesn't seek out the exact traumatic experience that made it so Catalina never swam in the Mediterranean again. It simply finds her with an identical dose of senseless brutality.

Forastera is therefore very much a coming-of-age story despite its unconventional trigger through the sorrow of death. By embodying her grandmother, Cata seemingly matures overnight to no longer let her grandfather's chauvinism or her mother's selfishness stand. She takes the role of steward once Pepa hires a caretaker to help around the house and rejects the role lustful teen wasting time kissing boys and drinking alcohol. This summer becomes a key turning point for Cata to recognize the preciousness of life and complexities of love.

It's a beautifully shot film as well with exotic vistas augmented by the terrace's recently installed glass railings for an unencumbered view of the sea. Iglesias infuses a couple of scenes with imaginative visuals that allow room for some supernatural manifestations courtesy of ants on the ceiling and reflective ghosts made of light. And the performances all teeter on the edge of coming undone so the tiniest bit of pushback can jog them awake to their own poor behavior. The distance between frustration and contrition is never far.

Homar wonderfully portrays Tomeu's grief with a desire for isolation even he knows isn't healthy. It's why he needs Cata's game to ween him off the black hole of despair that comes from an unexpected death. She, knowingly or not, holds his hand to guide him past it. And in so doing, Stein provides Cata the strength to do too much and the space to accept when it's gone too far. It's a fantastic breakthrough role of layered emotions as she becomes a vessel for a ghost born from her grandmother's memory and love that remains within.

7/10

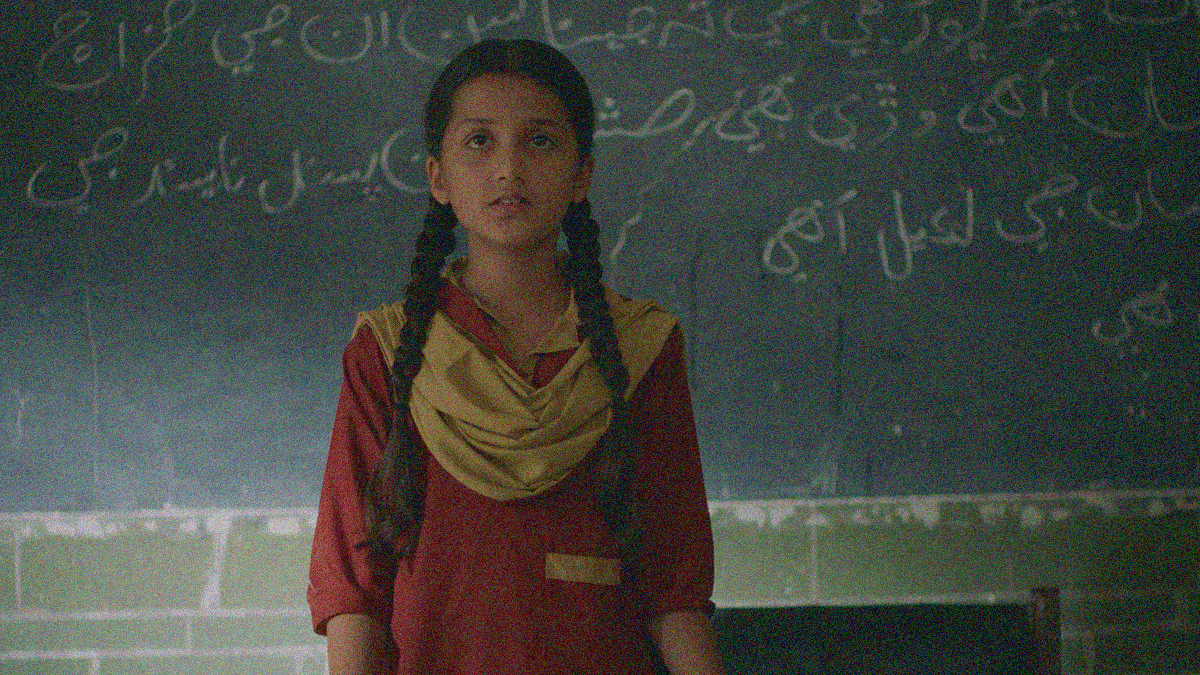

Ghost School

Religious fundamentalism is a powerful drug. You mustn't look further than the proliferation of American Evangelical Christianity since Ronald Reagan to understand this fact because the republican party has continued weaponizing their constituents' faith-based ignorance to exploit them into forgoing their own human rights ever since. Whereas we still have a few (dwindling) checks and balances providing safeguards against full ethnocratic rule, other countries like Pakistan do not.

Without proper oversight to ensure politicians are working in their community's best interests or a successful track record reiterating the importance of education for bridging a widening financial gap between rich and poor, any authority figure can shut a school down simply by saying a jinn took it over. Seemab Gul's feature debut Ghost School therefore reveals how young Rabia (Nazualiya Arsalan) can become the only person willing to fight for her own future.

Rumors start flying on the first day back from summer vacation thanks to a security guard barring entrance to school grounds. While one teacher falling ill is unfortunate, losing all three is a pattern. So, when the principal (Adnan Shah Tipu)—the person they look to for answers—blames it on a curse, who would dare question him? Since the same thing happened to the village's unfinished hospital and college too, it must be God's will. And since jinn are in the Quran, they must be real. Fantasy becomes a political shield for corruption.

What's really going on? The politicians promising new infrastructure for votes are splitting the necessary budget to do so amongst themselves. They use just enough to hire outside workers to start construction, eventually stop paying them so they leave, blame the result on supernatural forces not to be reckoned with, and keep cashing the checks. With nowhere else to go, poor students give up on education to learn a trade or become laborers instead. The cycle never ends.

Rabia believes in jinn too, but her love of learning demands context. She therefore roams the village to uncover her teacher's address and inquire when he'll conquer the spirit and reopen school. Some neighbors warn her not to meddle so the jinn doesn't grow worse. Others begin lamenting how it's all a smokescreen for governmental corruption. Rabia is cautiously parsing out the truth, but what's a ten-year-old's tenuous grasp on extortion compared to folkloric tradition?

You want to watch Rabia's unfolding journey with a smile because you don't want it to be true. But this is what happens in pious yet uneducated environments. The people are so afraid of demons that anyone who tells them demons aren't real becomes labeled as an accomplice to evil. And when you also have bureaucratic red tape to deal with (Rabia's teacher directs her to the principal and he to a district supervisor who might not even exist), the resulting futility tends to defeat those who were brave enough to get past the brimstone.

Ghost School uncovers the prevalence of apathy. A soon-to-be married neighbor tells Rabia not to worry about school since she'll be engaged soon too. The grocer admits he quit school after fifth grade because he only needed to know that much math to be his own cashier. The principal brazenly explains his position that education is a privilege rather than a right and transcending one's status would only deplete the "unskilled" labor force. Even Rabia's mother (Samina Seher) wonders if being illiterate is better than being bought as an educated servant.

Add gender (a boys-only private institution is the sole alternative option) to the equation and you see why Rabia is the perfect entry point for the London-based Gul to expose the complicated web of injustice Pakistanis must combat. To look through a child's eyes is to both blur the line between fantasy and reality and cut through it due to not being fully indoctrinated yet. Because Rabia still doesn't quite understand. She still hopes for a solution to "illnesses" like bribery that includes flying white horses. The lesson being taught is for our edification.

7/10

Retreat

Chilmark is introduced as a haven upon Eva's (Anne Zander) arrival from Berlin. The headmistress—for lack of a better term—Mia (Sophie Stone) welcomes her with open arms and a promise to provide the comfort and inclusivity she knows from experience has been difficult to come by. Everyone living within this sprawling mansion's walls has endured the trauma of growing up amongst the hearing. They've each followed Mia through a process called "The Way" to cope with their past and dismantle the labels thrust upon them. They reject the use of "Deaf" as a descriptor because they refuse to willingly other themselves. Here they can simply exist. Here they are "normal."

As Eva settles in amongst this isolated community (specifically populated and sustained solely by the non-hearing so CODAs and newly conceived children with the possibility of hearing don't siphon funds away from their central mission), Ted Evans' Retreat (born from a 2013 short of the same name) reveals one person at Chilmark is different. You see, Matt (James Joseph Boyle) arrived as an orphan at four years old. So, he knows nothing of the outside world or the isolation and anguish that comes with bigotry, abandonment, and abuse. For Mia and the others, he epitomizes this place's potential as well as its success. He proves they aren't beholden to society's ills.

What not even Matt fully understands, however, is that you can't gatekeep trauma. Sure, he doesn't know what it's like to be hated by family or let down by the government. But he also doesn't know what it means to experience anything beyond Chilmark's borders. He doesn't even know what it means to experience "The Way" since it was built to deprogram and assimilate—two things he doesn't need. Isn't that also a form of "othering," though? How should the one person everyone aspires to be feel when he isn't allowed to participate in their emotional and psychological healing? To live as a symbol can be just as dehumanizing as what they've withstood.

Well, he's been awoken to finally ask these questions now that Eva chose him to be a member of her "The Way" support team. Mia's right-hand Tracy (Anna Seymour) warns it's a risk, but she believes it'll work if he understands the process is about Eva and Eva alone. What Matt doesn't realize is that this means he will be relegated to a position once removed from the others. He will be reduced to that symbol of purity and dismissed as not having the same scars as everyone else. So, he must fight to be heard and explain how their utopia hasn't left him unscathed. He's merely been scarred in other ways. But no one is listening.

A sudden shift occurs. What began as Eva's story gradually slides towards Matt's perspective. As her stranger weaves herself into this place's fabric, the treatment he endures by their refusal to see him as an equal unwittingly plucks him from it. His character shaking free allows us to realize things aren't quite as they seemed. Certain aspects of their lives become colored with their own sense of oppressive indoctrination. This haven promising protection devolves into a bunker driven by fear. Why is Mia scared? Why is knowledge of the world beyond their walls forbidden? When does a sanctuary start becoming a cult?

Evans masterfully wields Eva and Matt as a spiritually tethered duo forever separated by the contrast of their worlds (Zander and Boyle are fantastic). As she crosses into his, he's forcibly displaced into hers. For Eva to understand the promise of Matt's life, he's exposed to the allure of what she's giving up. That doesn't mean he begrudges her decision or implores her to stop. No, he wants her to experience the all-encompassing love and familial bond he's always known. What he notices, however, is that she's granted permission to choose. Everyone has. Matt isn't therefore forsaking their kindness. He only asks to be granted the dignity to choose as well. He wants his Rumspringa.

There's a reason he can't, though, and it's a wholly authentic yet chilling one that's coming to light at the worst time considering Chilmark risks more than just having their idyllic bubble burst. As such, connections to M. Night Shyamalan's The Village are unavoidable insofar as what it means to strip away a person's autonomy under the auspices of protection. By flipping that revelation's impetus, Evans increases the tension and dread. Because this escape isn't born from the ticking clock of saving a life within. No, Matt's escape is a requirement for saving himself by finally contextualizing the identity foist upon him.

What makes Retreat so great is its disinterest in reducing the complexities of life into a binary equation. While something good can be built on the back of a heinous act, it cannot hope to ignore the damage wrought forever. Because that truth will fester until eventually revealing itself—a revelation that grows more unforgivable the longer it's suppressed. The best-case scenario is manipulating it again to buy more time. The worst is watching it become the destruction of everything and everyone. That's the trouble with totalitarian rule for the greater good. Its violence always turns inwards in self-defense.

While ensuring the film is completely told via British Sign Language by non-hearing actors is a crucial victory for representation, Evans (who is also Deaf) bakes this inclusionary tactic and its inherent challenges into the script too—especially as it concerns hearing audiences once the score becomes its own character augmenting the silent dialogue and expressive body language. The added suspense from this sound design and action is noticeable throughout, but you can't ignore that it's building towards something bigger. Unsurprisingly, the explosive finale born from the heavy cost of its central role reversal isn't easily shaken as a result.

9/10

Pulled from the archives at cinematicfbombs.com.

Green Book screened on September 11, 2018 at TIFF.