TIFF 2025: Day Three

Reviews galore

Another day is in the books with three films watched, three reviews filed (I'm saving two for tomorrow since I already have a ton of pre-fest titles below), and a delicious pulled pork sandwich from Heirloom Toronto consumed (my sole real meal as lunch became a scarfed slice of banana loaf from Second Cup Café).

My uncertainty about that haste was soon proven necessary, though, as I got into Scotiabank Theatre an hour before showtime for the No Other Choice press screening only to find about 200 people already in line. Absolute lunacy! Park Chan-wook has pull and the number of disappointed folks turned away were just notified a second press screening has been added today (9/6).

Left: Pulled pork sandwich from Heirloom Toronto. Right: The start of a mural on two large panels butted together at 90-degrees with images from THE PRINCESS BRIDE, AMELIE, and more.

It was a good day conversationally too despite pretty much running straight from writing sessions to viewing sessions save that Heirloom stop. I met Marya Gates from RogerEbert.com before Palestine 36 and had a great talk about the industry thanks to both of us liking to be first in line ... just in case. I watched No Other Choice with my regular TIFF travel companion these nineteen years, Christopher Schobert. And I got to say hi to fellow film lovers Adam Lubitow and Matt DeTurck from Rochester's The Little Theatre as I left Hamlet.

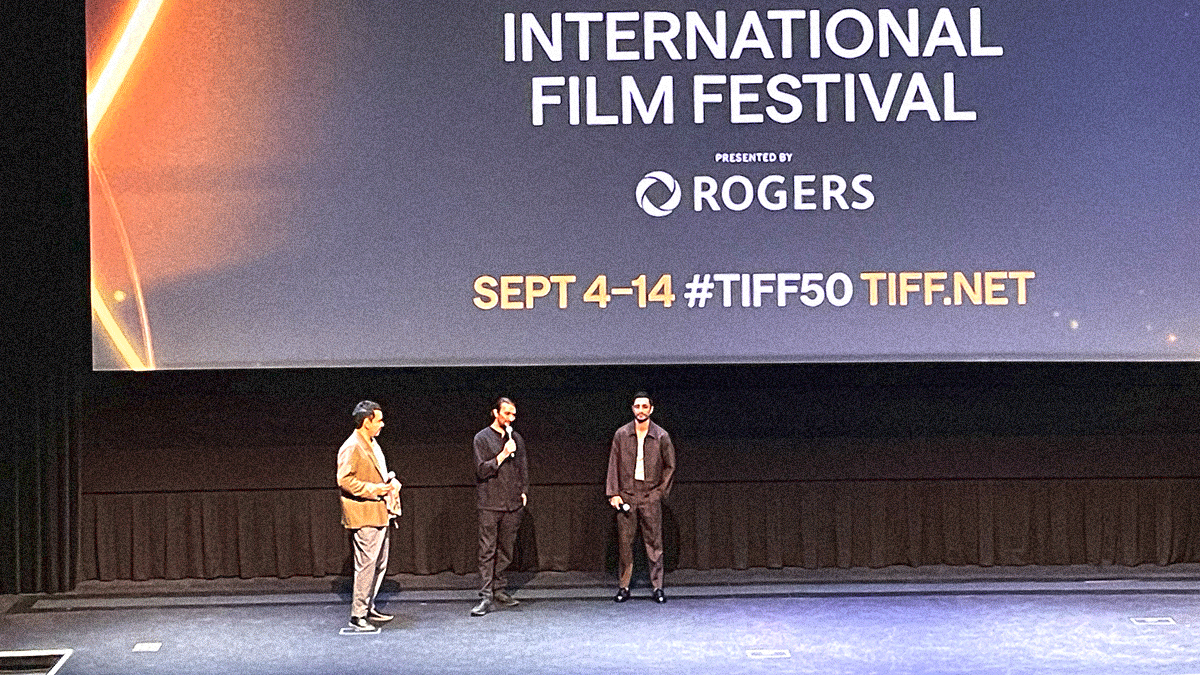

As for that last title, Aneil Karia and Riz Ahmed participated in a wonderfully insightful Q&A to talk about their process, affinity for the play, fatherhood, and a lot more. I was glad to have listened, but also remembered why it's best to run at the first sign of credits since it took about 20 minutes to finally leave the theater.

Today's schedule:

• Good Boy, d. Jan Komasa | Centrepiece | Poland, United Kingdom | English

• Fuze, d. David Mackenzie | Gala Presentations | United Kingdom | English

• Carolina Caroline, d. Adam Carter Rehmeier | Centrepiece | USA | English

Babystar

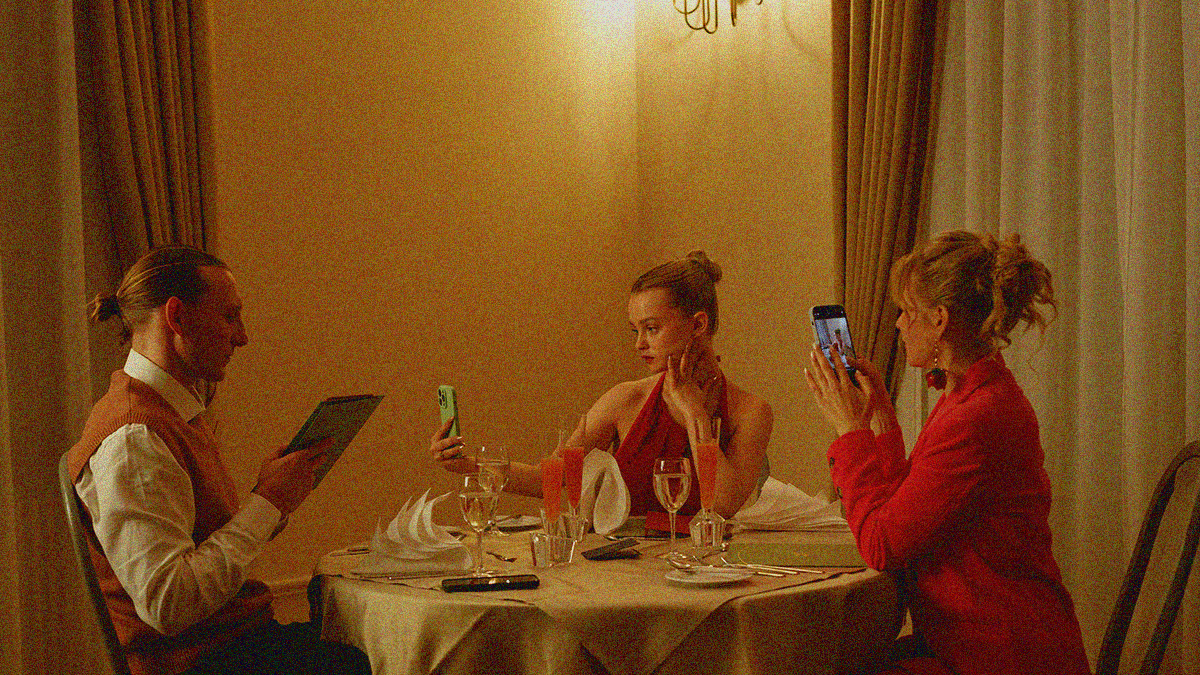

When your life has been used as content for global consumption since the moment of conception, how can you know if the person you see in the mirror each morning is truly you? How would you even realize that's a question you can ask yourself? Because Stella (Bea Brocks) and Chris (Liliom Lewald) have always asked Luca (Maja Bons) for her input. They've always asked for her consent. And from an outsider's perspective, one could feasibly believe those things are enough. That this sixteen-year-old internet celebrity is a partner in the Our Bright Life empire. But what is consent if saying "No" was never really an option?

As Joscha Bongard's Babystar (co-written with Nicole Rüthers) progresses, we glean more and more context about this family business. An idealist would presume this whole thing was born with Luca at the center. That Mom and Dad are the supporting players to her brand and she has the final say. A cynic would guess the truth, though. That Stella and Chris have been doing this since well before parenthood. They made money by advertising vacations and luxury products. They traveled the world and put every single second online. And once you accept that fact, you must ask the obvious question: Was Luca ever anything more than a prop?

It's no coincidence then that the film opens with Stella asking her daughter's opinion on gaining a sibling. Luca is justifiably averse to the idea. Yes, because she's only ever known herself as the star of the show and therefore the star of her parents' lives, but also because she isn't dumb. Call her naive, sheltered, or ignorant all you want since those labels are a direct result of the manipulation she's unwittingly been victimized by, but she's savvy enough to know the line between product placement and authenticity. Luca must wonder, "Why now?" Why wait sixteen years? Have ratings declined? Is it sweeps week? Has she aged out and suddenly become obsolete?

I don't know whether it's better or worse to realize it might simply be that Stella and Chris want to diversify the portfolio. Maybe they'll spin Luca off onto her own channel as she moves towards college, cars, dating, etc. Then they can rewind the clock to turn the home feed back towards "baby time" a full generation later with new technological advancements that ensure little overlap with the archive of videos they created during Luca's adolescence. You get the bump of a new cast member, the rejuvenated revenue stream of review content, and the potential double-dip of dividing and conquering via parallel life streams.

It might have worked too if they were just honest with Luca. Let her know the plan. Let her know it will provide her more autonomy. Make it a "graduation" of sorts towards greater freedom of choice. But what do they do instead? They treat it like a pitch. And when she declines? They try to manipulate her into changing her mind. Suddenly the veil is lifted. Suddenly she realizes she's never actually been an only child. No, Stella and Chris's first and favorite baby was always One Bright Life. Everything they've done and mythologized has been solely about them and them alone. Commence the teenage rebellion.

Bongard is keenly aware of the scenario he's created and never veers off-course insofar as the psychological damage born from it. In a pre-social media influencer world, Luca would have all the power to make their lives a living hell. Now, though? When controversy sells and precise messaging can indoctrinate a horde of parasocial hangers-on to believe whatever lie is constructed to sweep blemishes under the rug? It's become a game. A public tantrum can be dismissed as a deep fake. A genuine cry for help can be ignored and commodified for more clicks. Luca's only option is to extricate herself from the entire ordeal.

And therein lies the rub. Luca doesn't have the ability to know what such a divorce entails. She doesn't know how to be an independent member of society. The level of second-hand discomfort that arises from her projecting the rituals of her fabricated-yet-not persona onto people outside that realm is extreme. Because everything is filtered through the lens of content creation. Romance (with Joy Ewulu's Julie). New trends (at the expense of Maximilian Mundt's Simon). What it means to have a family (the uncanny valley of Luca infiltrating a stranger's home is wild). She can't adjust to life outside of her former prison.

Whereas the first two acts of Babystar really show an assuredness both in the filmmaking and concept, however, the conclusion can feel stagnant by comparison. I like where Bongard goes, but everything seems to happen too quickly for it to truly hit home emotionally. So much time is spent setting the table and flipping it over that it can be difficult to parse what's happening once Luca is forced to confront her state of suspended animation. Is she actually trying to walk everything back and find a way to accept her reality while also tweaking it for more control? Or is she just biding time to do what she ultimately does?

I don't know. And that's either a knock on how it unfolds or proof that I got duped too. It's somehow darker than I expected and not dark enough for the exposed nerve Luca becomes during the table flip. There's something about just how funny her fish-out-of-water schtick becomes (regardless of the depressing AI subplot that her only friend is a computerized algorithm of herself) that the way things return to the nightmare didn't quite mesh. It's still a very good film with impressive performances by Bons, Brocks, and Lewald, but I guess it just runs out of steam a bit in its bid to wrap things up.

PS: Prepare yourself for a full television-style opening credit sequence at the twenty-four minute mark and the insanity of it feeling like a bootlegged third season of "Severance" is about to begin.

7/10

Bouchra

"It’s an inventive approach turning the whole into a meta film for Bouchra to exorcise demons and reconcile emotions. That sense of personal attachment is apparent as you can tell this subject is close to the filmmakers’ hearts."

Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

Egghead Republic

German writer Arno Schmidt's novel The Egghead Republic published in 1957 with a wild look at the aftermath of nuclear war. Set in 2008 after grave global devastation, an American journalist is sent to report on mutated animals roaming an Arizona desert and a rumored "genius commune" known as the International Republic of Artists and Scientists in the Pacific. Its weird, fantastical satire promises centaurs, chauvinism, and even Schmidt himself. Considering our current politics, it might prove a bit more palatable than that other 1957 novel about a utopian society of free thinkers: Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged.

It's the sort of go-big-or-go-home source material that demands some bold genius of its own, so it's unsurprising that Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja would try their hands at (loosely) adapting it for the screen after their success bringing Harry Martinson's epic science fiction poem Aniana to life. Add Kågerman's experience working for Vice during its heyday and the idea to pull Egghead Republic through a contemporary lens of online journalism starts to come into focus. Because not even an apocalypse could stop a certain section of humanity from asking themselves how they might profit from it.

Enter Dino Davis (Tyler Labine), publisher, reporter, and raconteur of the infamous Kalamazoo Herald. Here's a man so unscrupulous that he would track down the great-niece (Ella Rae Rappaport's Sonja Schmidt) of the favorite author (Arno Schmidt) of a resident (Stephen Rappaport's Bob Singleton) at the Institute of Radioactive Arts and Science (IRAS) just to talk his way into an invitation to be the first press outlet to gain access to its restricted Kazakhstan desert locale. Yes, Kågerman and Lilja have compressed Schmidt's original two locales into one.

The year is 2004 and the Soviets and Americans have joined forces to create this haven for creativity and technological advancement on the site of the Cold War's worst disaster: the intercept and subsequent crash landing of a Russian launched nuclear missile by US forces. What better place to protect top secret work than an uninhabitable zone surrounded by extreme radiation? Everyone is carefully vetted. Everything is meticulously executed. And the site's most popular voice is apparently allowed to let his inner fanboy out to risk ruining it all.

Dino is using Sonja for access to IRAS. Sonja is using Dino for access to his magazine and the potential exposure of illustrating a cover or the poster for this journey's resulting film. His desperation inspires others to follow him (Arvin Kananian as his trusted cameraman Turan and Emma Creed as their unpaid intern / photographer / driver Gemma). Her desperation leads her into compromising positions at his behest. Because Dino is the kind of guy who pushes boundaries knowing he can buy his way out of the consequences. He says jump and Sonja is over the cliff before she can even think to ask, "how high?"

While the film teases the insanity to come (shadows of centaurs, an over-zealous Gina Dirawi inexplicably snapping photos of Sonja like she's a celebrity, and spoof-levels of curious interactions between military personnel obviously hiding secrets), its first two-thirds are a rather familiar look at influence's allure pitting those with creative control against those who create. There's Dino's sexism. Sonja's self-sabotage. Toxic dynamics forcing Sonja against Gemma and Gemma against Turan. The blatant babysitter runaround from Sergeant Barcoff (Merlin Leonhardt) and the reckless maneuvering to escape his grip without a safety net.

These machinations entertain thanks in large part to the actors proving very game to ramp up their characters' self-serving ambitions, but it does feel a bit like spinning wheels until they inevitably cross their respective points of no return. Because while the danger might not be exactly what they (and we) were led to believe, this situation is dangerous. Both because their thirst for Dino's attention drives them to do stupid things and because his thirst for power is fickle enough to put them in harm's way against their will. That's when the promise of hallucinatory absurdity is fulfilled.

I get why they've left the real insanity for the climax and denouement, but I truly wish we could have spent more time in it. Maybe I would ultimately think the opposite if Kågerman and Lilja did actually give it to me, though, so I'll appreciate what I got instead. Because it is a great reveal that recolors everything that came before while also introducing fresh possibilities for where it will go next. Egghead Republic more or less provides us a realistic lens with which to gaze at the result of its structural surrealism for so long that the veil lift onto pure lunacy ensures you'll have a smile on your face until the end.

It's not as polished or weighty as Aniara, but it's definitely a kindred spirit—albeit a distant gonzo cousin. Labine is great casting because Dino is right in his manic, no-filter wheelhouse. Kananian and Creed lend their characters an effective sense of morality that's constantly paper over by their inability to pass up the opportunity to advance their careers (despite knowing in their hearts that it's all a ruse). And Rappaport is effortlessly relatable as their pawn who's trying to find her footing because she doesn't realize the power she could wield here. Once she does? All bets are off.

7/10

Laundry

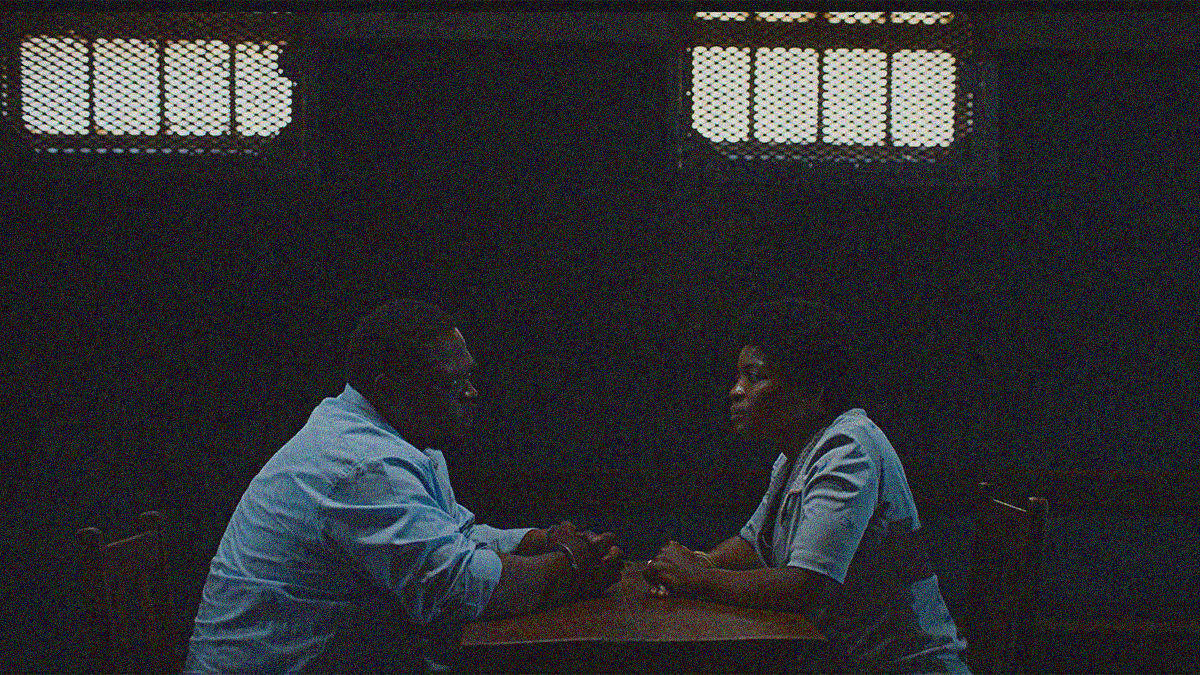

It's impossible to watch a film set during South African Apartheid and not find every oppressive aspect a one-to-one comparison point for Palestine and the decades its people have spent as second-class citizens to Israelis in their own home. The constantly changing laws making simple acts more difficult. The nation becoming an open-air prison due to it being nearly impossible to ever leave without permission. The inability to dream beyond survival itself and the reality that even that isn't guaranteed. The horrific series of tragedies that can be born from one member of the ruling class deciding to randomly assert his authority.

Enoch Sithole (Siyabonga Melongisi Shibe) had everything under control. His assistance to a British government official years prior granted him an exemption medal that bestowed certain privileges to which only Afrikaners were legally able to possess. It's what got him into a room with the renowned Dean Winters (Robert Whitehead) to cultivate a two-decades-long relationship that saw his laundromat thrive in a whites-only neighborhood known for its constant threat of harassment against Black citizens. With it, Enoch provided his wife (Bukamina Cebekhulu's Magdalena), son (Ntobeko Sishi's Khuthala), and daughter (Zekheteholo Zondi's Ntombentle) the rare gift of a comfortable life.

When writer/director Zamo Mkhwanazi's Laundry begins, however, it's all put at risk due to Winters' absence. That void emboldens some racist Afrikaners to make an example of Enoch for what they deem a level of charity that devalues their own superiority. And it doesn't matter if he does something to provoke them or not—who's going to believe the Black man in a room full of white officials? So, his inevitable incarceration becomes the first domino to fall. Then it's Magdalena needing to find his uncle to sign a bail agreement (Black women cannot). Then it's young Khuthala and Ntombentle trying to keep the business afloat themselves.

The film becomes a dramatic string of impossible decisions pitting necessities against desires in ways no free person should ever be forced to choose between. What begins as a familiar family dynamic of patriarchal divisions (Enoch wants Khuthala to take over the business despite his passion for music and his sister Ntombentle's passion for engineering and the laundry itself), soon zooms out to reveal the social dynamic of being Black under Apartheid rule and the hoops one must jump through to achieve anything. It's not about Khuthala picking art or commerce. That choice hides the real options: escape, subservience, jail, or death.

Khuthala is the de facto lead as a result of his father being in prison and his mother fighting to get him freed. We're watching him balance his duty as a son to help Ntombentle at the store (and attempt to assert authority over employees who know he can't) and his personal yearning for music. So, he often leaves early to jam with Lilian Mkhize (Tracy September) and her band instead. Rumor has it that they're heading to America and Khuthala proves he's talented enough to join them. The longer Enoch remains away, however, the heavier the burden his responsibility to family becomes.

What makes it more tragic is that his parents understand this conflict (perhaps more in their son than their daughter as Mkhwanazi's script perpetually ensures any dialogue with Ntombentle is interrupted when the topic of Khuthala arises—with future purpose). They would sacrifice everything to help him fulfill his dream if they weren't beholden to a ruling class trying its best to strip their humanity away. So, it falls on Khuthala to sacrifice for them instead. To willingly put his aspirations on-hold to ensure their survival under dire circumstances. But he could never have imagined the price he'd need to pay to do so.

Laundry quickly grows darker in scope and emotion as more of those dominoes fall. Because everything in South Africa at this time hinged on a quid pro quo. Enoch bribing Winters to keep that exemption medal in play despite the British leaving years ago. Human dignity being traded for the chance of earning exit papers to flee the injustice. Identity being compromised for the hope of safety as it concerns enrollment in a Catholic school's assimilation factory. And you don't just get an innocent Black man out of prison if you aren't willing to give up someone in his place—the ripples of which could travel anywhere.

It's almost rude to give us an insanely memorable musical sequence about halfway through as Khuthala makes his skill known and September's Lilian unleashes the full power of her voice because it truly gives us a false sense of hope that at least one of the Sithole family will make it out. The moment they finish playing, though, he admits the situation at home is too volatile to simply abandon it. Cue an instant whiplash from the high of a dream to the pain of reality. And the steady decline only grows worse considering the few victories they do earn seem to raise the stakes higher and render success more unattainable.

The main cast is phenomenal with Shibe and Cebekhulu providing a resonant sense of moral pride in the face of grave prejudice while Sishi and Zondi delicately traverse the adolescent uncertainty of not realizing the consequences of their demand to rebel and be heard. The latter's characters are forced to grow-up overnight once their choices begin to wreak irrevocable havoc upon the people they love. It all culminates into an unforgettably heart-breaking epilogue showing just how tenuous security is under Apartheid. Because nothing can be earned amidst such an imbalance. It can only be given.

8/10

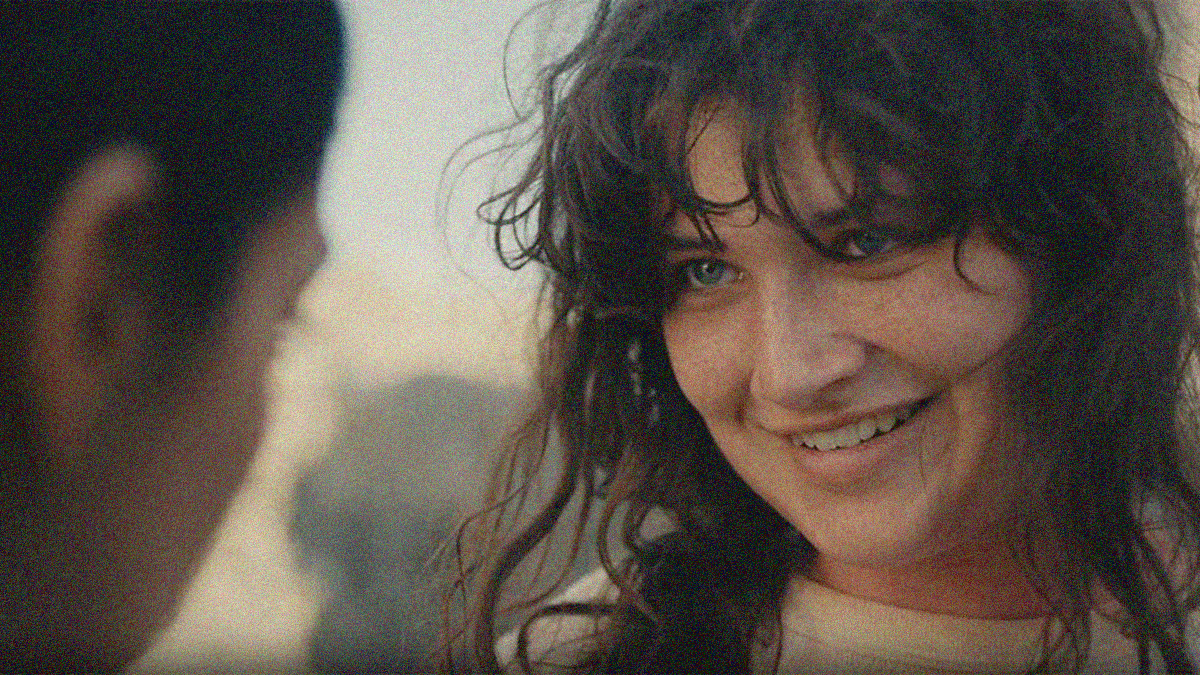

Little Lorraine

The story is true. A small village in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia with less than one hundred close-knit citizens became a key point of interest in an international cocaine smuggling ring. The Canadian coast became the entry from which the drug circulated throughout North America in the 80s and, as the text at the end of Andy Hines' Little Lorraine explains, few arrests were made. Because these folks don't talk. They understood the dire straits of their neighbor because they faced the same. And when one person did earn a windfall, the money generally found its way into the community at-large. No jealousy or greed amongst them.

Born from a 2022 song by Adam Baldwin (not that one) in which Hines directed the music video (both for that purpose and as a proof of concept), the two friends worked to flesh out the tale of Jimmy (Stephen Amell), Tommy (Joshua Close), Jake (Steve Lund), and Uncle Huey (Stephen McHattie) into a feature-length script. It starts down in the coal mines beneath the Atlantic Ocean as tragedy strikes to put another nail in the coffin of Little Lorraine's economy. The local fort had already bought up much of the residential land to expand its tourism footprint and now there was one less employer to help stem the bleeding.

That's when a man everyone thought was dead returns. A man Father Williams (Sean Astin) has no qualms calling the village's "prodigal sinner" due to a laundry list of past crimes. Huey says things are different this time. He explains that he only wants to get to know his nephew's family (Auden Thornton as Jimmy's wife Emma and their two kids) and help turn the area's luck around. So, he recruits Jimmy and his two friends to help work a lobster boat under French Canadian captain Thibault's (Mike Dopud) tutelage. The work is hard but honest and the money more than they ever earned underground. But it's too good to be true.

These types of stories don't have much new to say insofar as the act itself. There's the bumbling local cop (Matt Walsh), the vendetta-driven Interpol agent (J Balvin in his feature film debut), and the flamboyant middleman facilitating the product (Rhys Darby). There are close calls, increased paranoia, and the inevitable Catholic guilt that leads to alcoholism, product sampling, and confessionals. Jimmy and the guys can't trust Huey. He can't trust them. It becomes a ticking clock until one of them ends up dead in an "accident" or by their own hand. The stress hits so hard that someone is bound to crack.

So, the appeal with this iteration is that vibe of unwavering loyalty. The certainty that Father Williams will protect his congregation. That the villagers understand authorities beyond their borders are a huge part of why they're in this mess. When Blavin's Agent Lozano arrives and asks a deputy for a black coffee, it's not received with a mound of powdered creamer as a joke or hazing ritual. No, it's a legitimate sign of disrespect because they know his only purpose is to put their friends in jail. If Interpol and the Canadian government truly cared about them, they wouldn't have needed to turn to smuggling.

That whole subplot with Lozano is mostly a distraction to infuse comedy both in how he's treated by the locals and his attempts to help them (i.e. importing Colombian coffee). It's fun watching Walsh's Chief Douglas wade through the angry phone calls of fishermen being harassed at the docks and Darby is always good for a couple laughs. Even McHattie brings some humor by playing his role with an effective dose of tempestuous villainy. He'll rile himself up to diffuse heavy situations posing a threat with a joke only to then pull a knife on those who caused them so they remember who's in control.

Beyond the color provided by these performances, though, the crime itself is pushed to the background. The real meat lies with Jimmy, Tommy, and Jake unraveling. Amell is the stoic leader with his head on straight (besides a brief spell off the wagon), so it's Lund and Close who provide the drama once the pressure becomes too much to bear. Even so, I didn't quite anticipate where things would ultimately go. Whether the familiarity or the humor, I wasn't prepared for the village to match Huey's ruthlessness. I'm glad it did, though, because it turns a decent rainy day TV movie into a worthwhile rental.

6/10

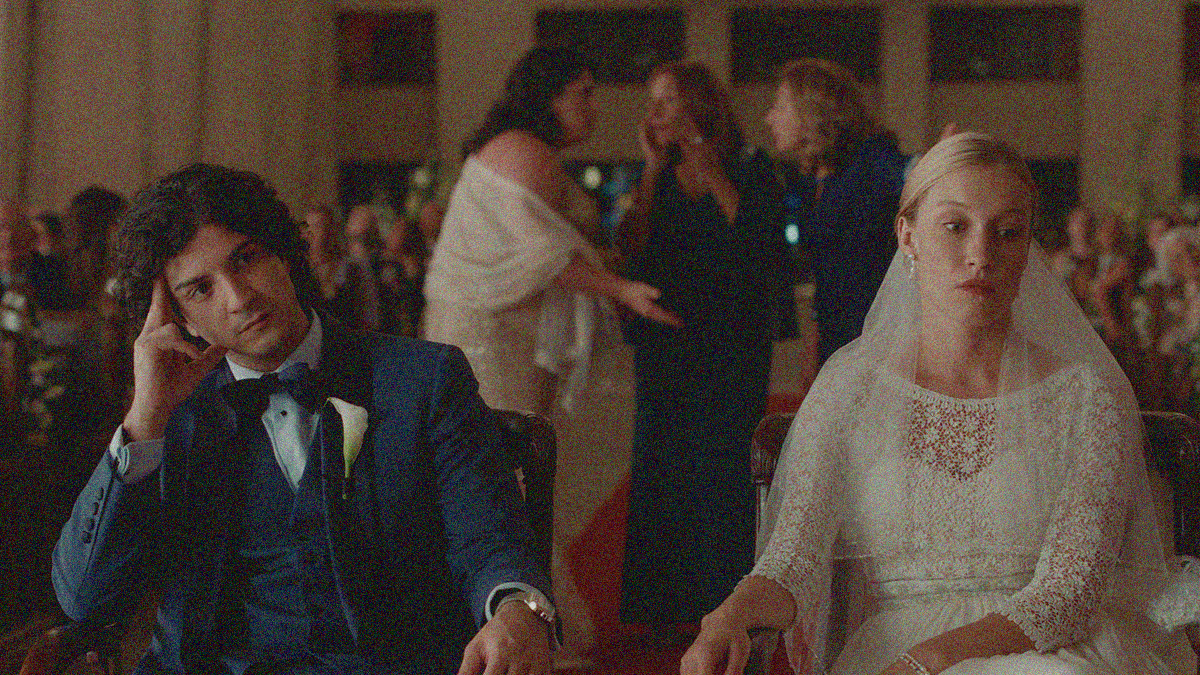

Lovely Day

Despite the English title (the original French translates to A Thousand Secrets, A Thousand Dangers) and the sentiments to Bill Withers' song as selected by Alain (Neil Elias) and Vir (Rose-Marie Perreault) for their wedding, this day of celebration proves anything but a Lovely Day. Is it a result of bad luck? The powers of an evil eye? Absolutely terrible karma on behalf of the groom? Or is it simply the complex nature of being humans who rely upon other humans to support and love them? Because the evening does ultimately end with a smile. It's just tough to imagine that being true considering all that occurs.

Adapted by director Philippe Falardeau and writer Alain Farah from the latter's autobiographical fiction novel of the same name (hence the lead character also sharing his), we know things are going to be bumpy from the start due to Dodi (Mackbouba) dropping the ball on his Best Man duties. The plan was to pick Alain up in a rented Mustang. The reality sees them driving in bumper-to-bumper traffic just thirty minutes before showtime inside Dodi's tow truck instead. These brotherly cousins are thick as thieves, though. Alain has incredulously handled his best bud's questionable reliability for decades. It's par for the course.

Dodi frustratingly exits the cab often to help toss trash bags into a garbage truck and move construction blockades—anything to propel them forward so they aren't completely late. As anyone who has ever participated in a wedding knows, however, you're "late" if you're not present at least an hour in advance to assist with any finishing touches. So, arriving at the church proves just as chaotic as the ride there. Vir ignores tradition to welcome her husband-to-be. Ruby (Joëlle Thouin) makes a beeline for Dodi (her boyfriend) to give him a hard time. And the risk of Alain's estranged parents causing a scene has him bracing for impact.

Rather than enter the venue with them, though, Falardeau rewinds things to provide us a new timestamped entry point of twenty-four hours before the wedding. We've already seen a few flashbacks of Alain's childhood (presented with a change in aspect ratio from the full-framed stress of the current day to widescreen memories of the past) for context to his painful bowel troubles and constant threat of a panic attack, but this is a full restart wherein he arrives at his apartment with his tuxedo and promptly checks the task off his to-do list. Vir shows up. Dodi is already present. More context is shared.

The entire film unfolds non-linearly as a means to shroud certain revelations in the edit while exposing others through what could be construed as nightmarish visions compounding Alain's already lengthy catalog of ailments. Things like Vir pushing his hand away at the reception or him turning white as a sheet from a phone conversation for which we don't hear the other side. These tiny actions influence and/or foreshadow the drama coming next, but there's also additional information to be infused at a later time to recolor things upon a replay. We go nineteen years in the past, thirty minutes into the future, etc.

And through it all we see the trauma young Alain endured to make him such an emotional mess. That's not to say he doesn't have a real medical condition in Crohn's disease. It's just tough to know where the physical pain of that affliction ends and the psychological conditioning from his Egyptian father Elias (Georges Khabbaz) telling him that admitting he has it is a weakness begins. The same can be said about his Lebanese mother Yolande (Hiam Abou Chedid) and the obvious resentment towards her ex that inevitably projects upon her son from having to be the one perpetually taking care of his suffering.

There are also deep-seated feelings born from childhood melodrama. Dodi is still Dodi at any age, but the unrequited love for Constance (Electra Codina Morelli) and racism towards Baddredine (Farés Chaanebi) open wounds that Alain is still reckoning with now. The latter point intrigues because cultural blurring is a common thread from multiple angles. Like Alain's light skin allowing him to call himself Québécois despite his Arab heritage or his choice to marry in a Catholic church as a Maronite instead of at a Greek Melkite parish. (As a Lebanese Maronite myself, these religious choices can get blown out of proportion.)

So, of course Alain is a basket case. The lesson here isn't about healing him, though. It's to smack him awake to the fact that everyone loves him anyway. The anxiety and pain have clouded his judgement so thoroughly that he's unwittingly throwing himself a pity party whenever something goes mildly (and often hilariously) awry rather than recognizing how he's not the only person with feelings about or ownership in this joyous event. Alain begins to abandon those who would never abandon him and they ask for his forgiveness. The hope is that he'll eventually accept his complicity and finally ask them to forgive him.

The comedy from this never-ending series of absurd pratfalls makes Lovely Day an enjoyable experience, but learning about and reconciling with the bottled-up anger within Alain renders it so memorable. The character is extremely relatable considering we've all positioned ourselves as the star of the story to accommodate the rage felt when being let down, nerves of presuming someone will ruin things, and shame in grasping way too late that the trouble is mostly our fault. But it's not about you. Alain sees Dodi's selfishness. His parents see it in each other via hindsight. It's time to turn the mirror inward and acknowledge it in himself.

8/10

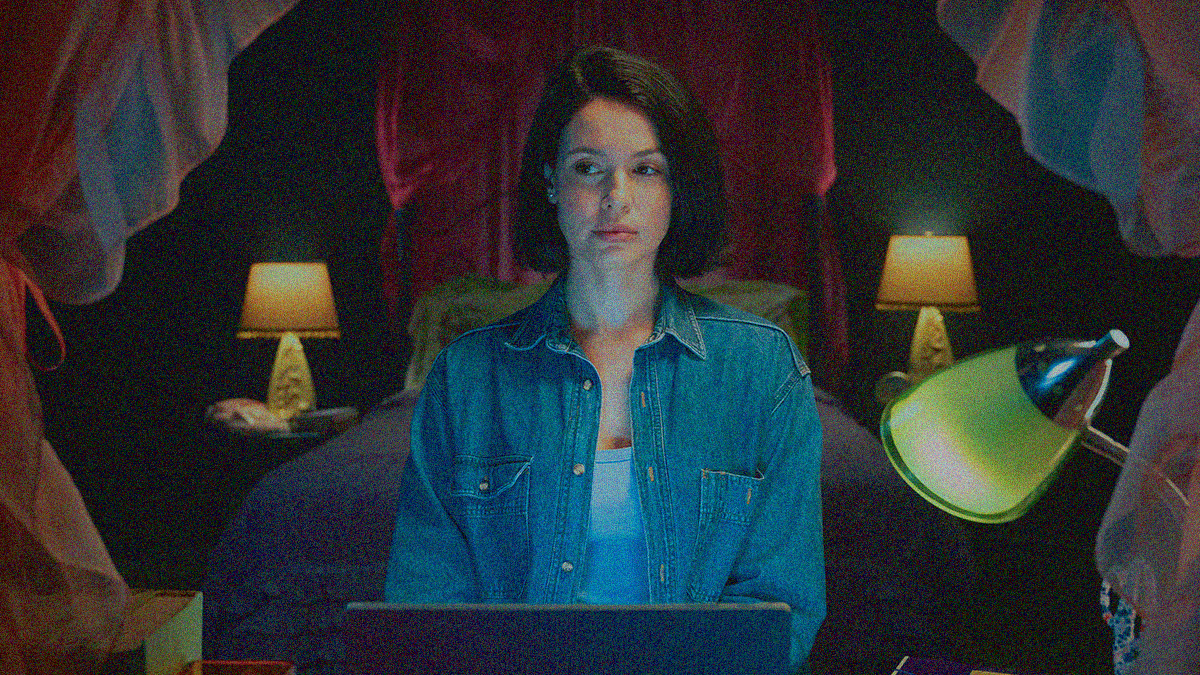

Modern Whore

Being a published author, performer, and activist all while still being a sex worker, there's truly no better person to tell Andrea Werhun's story than herself. She's done so with her collection of short stories entitled Modern Whore: A Memoir (accompanied with photographs by Nicole Bazuin). She's done it through short films directed by Bazuin using a hybrid style wherein Werhun re-enacts her own experiences. And now the pair collaborate again on a feature adaptation to shed more light on a subject that's remained stigmatized and criminalized despite a gradual social shift bolstered by the current normalization of OnlyFans.

It's an entertaining piece thanks to Bazuin and Werhun's comic sensibilities to subvert dark subject matter with intentionally goofy and/or campy sequences satirizing public perception through a historical cinematic lens, but it's also a crucial work insofar as embracing the vulnerability necessary to humanize laborers within a profession that's been victimized and villainized for millennia. You won't be surprised to learn one of the ways to do so is by using parallels with and terms from "respectable" careers. Vixen Vu says it best when declaring her wish is for sex work to be spoken in the same breath as chiropractic care. "Not everyone believes in it, but the people who love it ... love it."

Vu, SJ Raphael, Kitoko Mai, and Robin Banks are all current or former sex workers Werhun met in the industry and their insight proves invaluable to expand upon the vignettes she recreates from her life. There's talk about being gender neutral and choosing to lean feminine because it pays more. There's the double-standards faced by Black women in the industry. This cohort is also just beneficial insofar as offering different perspectives on key universal concepts such as shame. Because Werhun is the first to admit that being a white, cisgenger, and conventionally feminine woman skews things and she isn't afraid to bring other voices in for a more robust education.

This is still her story, though. Werhun takes us from having the initial idea to start escorting while at university to making a career of it to pivoting into stripping—all while continuing to hone her art in the hopes of one day being able to sustain herself on it alone. We hear the horror stories, learn the terminology (i.e. "trauma porn"), and watch it all through a Technicolor filter allowing Werhun to embody every stereotype she can conjure as a means to disarm the viewers' preconceptions and let the wisdom and context being taught in. Because there's nothing more effective than interrupting a LOL with a record scratch of reality.

The trigger warning that plays beforehand isn't therefore to be taken lightly. Not by prudes since the film definitely isn't shy about nudity, but, more importantly, not by sexual assault victims considering the abuse that's restaged. Yes, Werhun and Bazuin want Modern Whore to be a good time, but they won't sacrifice emotional authenticity to do so. The over-the-top theatricality with costuming, aesthetic genre homages, and caricatured "Johns" is merely a tool. It's the shiny packaging that gets us to buy into the salaciousness we bring to the subject before stripping it away to see the women fighting to survive a dangerous occupation and the warped public perception making it so.

Hence the support system—not only from her four contemporaries, but also Werhun's boyfriend, her favorite stripping client, and her very Catholic mother. The two men provide a nice contrast to the revolving door of creeps and sadists populating her tales (not that there aren't a few sweethearts sprinkled in too) because it means something to let morality and logic into a subject too often buried beneath shame and righteous indignation. It helps us remember that the taboo surrounding sex work is driven by outsider jealousy, misogyny, self-hate, and fear. Because villainizing and victimizing sex workers is always an excuse to justify being the villain who victimizes them.

It's why the whole film ultimately moves towards a need to create a new label born from the fact that telling your own story means you can finally be painted as the hero. That doesn't mean there isn't still risk involved (outing oneself as a sex worker can provide evidence of "objectionable behavior" to be used against you by landlords, employers, and courts). Just that there's an alternative side to the one we've been indoctrinated into believing is an objective truth. Look no further than the inclusion of Werhun's mom. She doesn't approve of what her daughter does and fears for her safety every day, but she's also extremely proud of her bravery to unabashedly be the woman she wants to be.

7/10

Palestine 36

"Whereas so many Hollywood examples reduce this region’s story to terrorism, Palestine 36 gives it the care necessary to remind us how that label is often used by oppressive forces to maintain their control."

Full thoughts at The Film Stage.

Steal Away

Set in an unknown place under the watchful eye of a domineering militarized force simultaneously calling to mind slave catchers in the American South, Nazi soldiers during World War II, and ICE disappearing immigrants in today's United States, Clement Virgo's Steal Away holds an intriguing ambiguity as to the identity of debutante and refugee. The obvious assumption is for Fanny (Angourie Rice) to be the former and Cécile (Mallori Johnson) the latter because that's how history has handled race for millennia. But the lavishly dressed Cécile riding through a bustling Black market community makes us think otherwise.

The only white person we see during this entire opening journey is Fanny peering out the window of a giant house. So, when Cécile and her mother are met by Black men and women welcoming them and taking their luggage, it's not difficult to imagine they've just come home and the young woman upstairs is their ward. Only when Florence (Lauren Lee Smith) comes walking out the front door to greet them do we realize our original assumption was correct. All those Black characters are servants. Cécile and her mother will start working too. But it's a symbiotic dynamic because Florence offers them citizenship papers in return.

This realization had me wondering why Virgo and Tamara Faith Berger didn't just fully adapt Karolyn Smardz Frost's non-fiction book Steal Away Home instead of simply using it as inspiration. Because it's one thing to use reality to shape a fairy tale that delivers something beyond its source material. It's another to just give us the exact same thing. Sure, there are differences insofar as these Black characters not being actual slaves, but do they have autonomy? Yes, the soldiers abduct illegal immigrants rather than escaped property, but is the inclusion of one Eastern European necessary when the act itself has inherent global resonance?

I'd argue "No" to both points and, as a result, kept waiting for something more to occur. That presumption is ultimately on me, but I don't think the film's desire to stay so grounded that its "alternate universe" take proves little more than a superficial filter is wholly innocent. Strip away the excess and this is just an Underground Railroad tale of freedom from oppression. So, its value will therefore rest with how captivated you are by the relationship of its two leads. One that's steeped in jealousy because neither Cécile nor Fanny truly know what's going on. Once they do, however, that sin melts away to expose adoration.

I did find it compelling because Virgo and Rice never allow Fanny's actions to become rooted in malice. She likes Cécile's clothes and hair. She lusts after Cécile's boyfriend Rufus (Idrissa Sanogo). She yearns to be seen as a figure of desire rather than just another spoiled kid being laughed at by her mother's guests. Watching the way Florence interacts with Cécile and her doctor's Black baby earns some jealousy, but it's not because Fanny wants to replace the new arrival. It's because she wishes to be her equal. Will Cécile see it that way from the outside? No. History all but guarantees the opposite. Fanny must earn her trust.

That's the subplot that kept me engaged when the bigger picture surrounding Florence's talk about "eggs being a woman's lifeblood" comes into obvious focus. Every detail concerning the specific way in which this plantation operates on the backs of immigrant bodies is out in the open from the moment Cécile sees a cork board of all the young foreigners who slept in her room previously. None of those revelations carry the weight the filmmakers surely hope, but Cécile and Fanny finally comprehending them does. Because the latter understands that the former's pain is shared. If it can happen to her, it can happen to anyone.

It's the same lesson our current moment is learning under Donald Trump's regime. The lesson we should have learned eighty years ago when Pastor Martin Niemöller wrote "First They Came". There must be a line that morality won't allow you to cross. There must be a person to enforce it even when they were themselves bred to help erase it. That's who Fanny is here. She's a self-fulfilling prophecy considering her compassion for women like Cécile was born from her mother constantly exposing her to them. The need to humanize these immigrants to maintain respectability on the surface ensures Fanny won't just turn away.

Johnson and Rice effectively toe that line as their characters let their own presumptions dictate initial actions until their true selves are laid bare. The world around them is also beautifully rendered in its out-of-time and out-of-place aesthetic (with a bit of fantasy as it relates to a premonition). But I won't lie and say I wasn't often confused by that subterfuge not having any payoff. I kept thinking I was missing something, but there wasn't anything to miss. Steal Away is merely a well-told story of oppression in an unnecessarily convoluted package. Some will love it, some will hate it, and, those like me, will simply move along.

6/10

Pulled from the archives at cinematicfbombs.com.

Juno screened on September 8, 2007 at TIFF.