TIFF 2025: Day Twelve

And the winners are ...

The last time a Chloé Zhao film won the TIFF People's Choice Award (presented by Rogers), Nomadland ended up also winning Best Picture, Director, and Actress at the Oscars. Could lightning strike twice now that Hamnet achieved the same honor? We shall soon find out.

It seems the Canadian angle helped Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie win Midnight Madness over two of the buzziest films I heard about while in Toronto. And perhaps there was some pro-Zionist ballot-stuffing for the documentary prize considering the controversial The Road Between Us: The Ultimate Rescue only had one public screening. Unlike in the past where you needed a physical ticket to vote, you vote online now. Terms and conditions say the fest compares email addresses to sold tickets and vote numbers to attendance, but that doesn't mean everyone at Roy Thompson didn't just blindly vote regardless of quality.

Here are the rest of the award winners at TIFF 2025:

TIFF People’s Choice Award presented by Rogers

Winner: Chloé Zhao’s Hamnet

First Runner-up: Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein

Second Runner-up: Rian Johnson’s Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery

TIFF People’s Choice International Award presented by Rogers

Winner: Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice

First Runner-up: Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value

Second Runner-up: Neeraj Ghaywan’s Homebound

TIFF People’s Choice Midnight Madness Award presented by Rogers

Winner: Matt Johnson’s Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie

First Runner-up: Curry Barker’s Obsession

Second Runner-up: Kenji Tanigaki’s The Furious

TIFF People’s Choice Documentary Award presented by Rogers

Winner: Barry Avrich’s The Road Between Us: The Ultimate Rescue

First Runner-up: Baz Luhrmann’s EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert

Second Runner-up: Nick Davis’ You Had to Be There: How the Toronto Godspell Ignited the Comedy Revolution...

Platform Award

Winner: Valentyn Vasyanovych’s To The Victory!

Honourable Mention: György Pálfi’s Hen

Best Canadian Feature Film Award

Winner: Zacharias Kunuk’s Uiksaringitara (Wrong Husband)

Honourable Mention: Min Sook Lee’s There Are No Words

Best Canadian Discovery Award

Winner: Sophy Romvari’s Blue Heron

Honourable Mention: Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset

International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) Prize

Winner: Lucía Aleñar Iglesias’ Forastera

Network for the Promotion of Asia Pacific Cinema (NETPAC) Award

Winner: Jitank Singh Gurjar’s In Search of The Sky

Best Canadian Short Film

Winner: Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski’s The Girl Who Cried Pearls

Honourable Mention: Heather Young’s A Soft Touch

Best International Short Film

Winner: Joecar Hanna’s Talk Me

Honourable Mention: Arvin Belarmino and Kyla Danelle Romero’s Agapito

Best Animated Short Film

Winner: Agnès Patron’s To the Woods

Today's schedule:

• Junk World, d. Takahide Hori | Midnight Madness | Japan | Japanese

• Ni-Naadamaadiz: Red Power Rising, d. Shane Belcourt | TIFF Docs | Canada | English, Anishinaabemowin

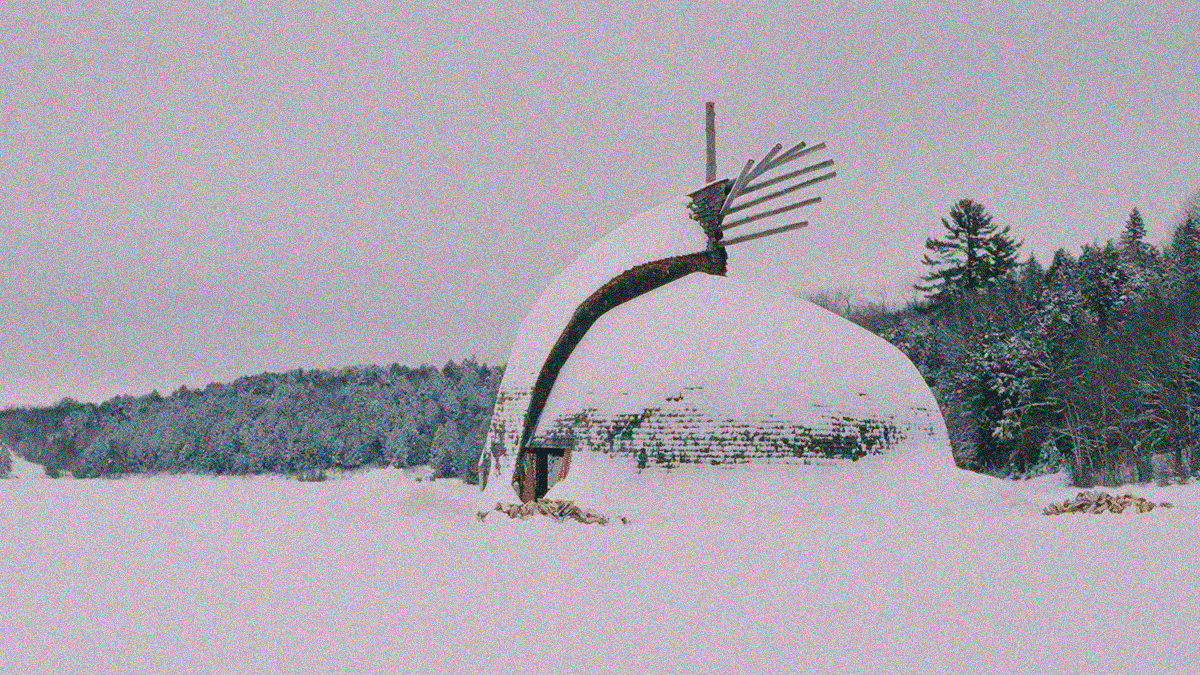

Aki

More than a love letter to home, Darlene Naponse's Aki is a document of identity through the land (for which the title is an Anishinaabemowin translation) that holds her community. Completely set within the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek territory (previously known by its colonizer name Whitefish Lake First Nation), the film takes us through the seasonal cycle of growth, frost, and rebirth by wielding an omniscient view of nature, animals, and people enjoying their lives.

As Naponse explains: "We are not defined by what has been taken from us. We are defined by our endurance, our relationships, our laughter, and our responsibilities to each other and to Aki, this land that gives us life." So, she strips away the outsider influence to depict Native stories through trauma and loss and reclaims the territory's reality of harmonious existence with all living things. Hunting. Playing. Dancing. Laughing. All to the melodies of Cris Derkson's cello.

This is a wordless production save ambient chatter during scenes of gathering (a powwow, children playing hockey, etc.), so understand going in that the point is to experience rather than learn. We gaze over the gorgeous landscapes and follow as inhabitants check maple syrup taps, skin a rabbit, or prepare for celebration. Beyond kids waving at the camera during a game or a table of Bingo players pointing towards us, there's no direct interaction with the cinematic process.

Naponse even pretends the lens is a bee in one scene, bobbing through foliage before ultimately finding the insect floating nearby. There are a few instances of split-screen too wherein half the frame is of a stream, tree, or flower and the other half zooms in closer to catch its textures. The only aspect of Atikameksheng Anishnawbek that doesn't find the camera lingering is evidence of industrial infrastructure. Those moments leave our view as quickly as they arrived.

Is Aki going to be for everyone? No. I'm not even sure it was for me. But you cannot deny its success at capturing the ethos of a place and people through unhindered images of life running its course. It's worth the attempt to let its beauty wash over you because its subject is deserving of exposure on its own terms removed from stigma, tragedy, and interference. This is the Anishinaabe. Humanity, nature, art, culture, food, sport, earth—it's all one and the same.

Mama

Mila (Evgenia Dodina) would do anything for her daughter. In so doing, however, the line between acting in Kasia's (Katarzyna Lubik) best interests and for what she believes Kasia's best interests should be inevitably blur. So much so that "mother" and "daughter" become hollow labels only provided meaning by past nostalgia and faded dreams. Since Mila's need to support her family took her abroad to work as a live-in cook/maid in Israel, these two women haven't seen each other in a very long time. They've become strangers.

An unexpected injury at the start of Or Sinai's Mama suddenly forces a reunion for which neither was ready. Mila was engaged in a steamy affair with a younger man in Israel (Martin Ogbu's Martin) while her husband Antoni (Arkadiusz Jakubik) held down the fort in Poland. He and Kasia found assistance from Natasza (Dominika Bednarczyk)—a relationship that became more for both than maybe they expected. That's the risk of long-distance dynamics, though. That and finding yourself out of the loop on important life developments.

The latest: Kasia is getting married. And if that were the entirety of the news, Mila could genuinely be thrilled. Rather than explain the full situation, her family allows bits and pieces to be revealed as new and not so fun surprises. First is the news that Kasia will be quitting school to move where Yurek lives. She says she wishes to finish, but that the curriculum grew "too hard." Mila knows that doesn't sound like her daughter, so the second bombshell arrives as you might imagine. This whirlwind is a product of love, but also a forthcoming bundle of joy.

Mila goes into overdrive to create solutions to problems that only truly exist in her own eyes. Is all this news shocking? Sure. Is it unmanageable? To hear from Yurek's well-to-do and caring parents, no. What transpires is therefore more about control than anything else. It's about Mila losing her grip on the future she planned for their trio years prior that no longer fits their current circumstances. Building the big house with her Israeli money. Seeing Kasia become a professional so she mustn't leave her own children like Mila. Pretending everything was fine.

What can she do in response? The obvious answer is to listen and evolve. Mila's impulse is to instead reassert dominance as though she was still more than a money-making appendage to be loved in concept rather than practice. She plays mind games with Natasza to mark her territory. Puts words into Kasia's mouth as far as going back to the original blueprint of graduation and career before motherhood. She even floats the idea of an abortion to put everything on-track while promising to remain and supervise. And she won't take no for an answer.

It's a myopic strategy destined to fail so horribly that Mila might never be able to recover as is, but Sinai introduces even more drama to make matters worse than you could ever imagine. These choices never feel inauthentic, though. The filmmaker simply has a keen sense of who her lead character is and just how selfish she can be when threatened. And the film is better for it too because it needs the ability to progress at a fast enough speed to ensure a breaking point arrives that cannot be taken back. A price must be set for believable resolution.

That's exactly what we receive courtesy of Mila eventually recognizing the result of her decisions—both now in her hasty attempt to erase recent developments and then in her necessary choice to leave and set it all in motion. What truly makes Mama a success, however, is its refusal to let Mila wallow in regret. This is a strong woman who did what had to be done. Yes, the fruits of that labor aren't what she hoped and the reality of what's next unavoidably holds infinite sorrow, but what's done is done. You remember the why of it all and just keep going.

The acting is stellar across the board, but special mention must be made for Bednarczyk since her Natasza could have been a throwaway point of conflict in a less assured script. This role and performance are instead handled with maturity and grace knowing what it is she's done as well as the truth that her place cannot be erased as easily as one might assume. She is the familiar figure of love now. Maybe Kasia and Antoni could forget her if Mila truly stays and works to reclaim her spot as matriarch, but that's an uncertain and steep uphill battle.

So, it's no surprise Dodina sticks with you upon leaving the theater. She imbues Mila with the pragmatic dominance to grab hold of the reins she didn't realize she lost and the devastating anguish when forced to acknowledge their absence. It's such a good character because she's ruthless when fighting for what she wants yet dignified in defeat. That doesn't mean she won't try to explain herself or work to be forgiven. She just won't also disrespect everyone involved by refusing to recognize when the time for contrition has passed. Some fights can't be won.

7/10

A Poet

Óscar (Ubeimar Ríos) wakes up every morning passed out in the street with a bottle in hand. What little he remembers from the previous night is screamed at his mother with a child's indignation because it usually concerns needing a loan for an idiotic investment scheme. He still calls himself a poet because he published a couple promising books decades ago, but he's just unemployed. Too proud to admit his failures and too lazy to prove the world wrong, Óscar sulks in the corner and pities himself as the most misunderstood genius alive.

Writer/director Simón Mesa Soto lays on the absurdity of this self-identity thick during the first chapter of his latest film A Poet (one he admits rushing to finish—filmed between January and February 2025 before submitting late and being accepted to Cannes and thus placing a clock on final cut—but thinks its unfinished quality enhances the subject matter and themes). One of the best moments of the whole is at a poetry reading where Óscar's preamble runs so long that the moderator must finally interrupt him to ask what poem he's chosen to share.

Despite his full aversion to demeaning his talent by accepting a high school teaching job, Óscar inevitably relents if for no other reason than to buy his estranged daughter's (Alisson Correa's Daniela) love by offering to pay her college tuition. What he couldn't have expected, however, is that one of his philosophy students writes poetry too. And she's good. Enough to approach his more successful contemporary Efraín (Guillermo Cardona) about helping him mentor Yurlady's (Rebeca Andrade) impoverished youth to greatness.

The film becomes one of parallels, mirrors, and exploitation. Óscar uses Yurlady as both a surrogate for his own daughter and an artist to live vicariously through. Efraín uses her poverty to raise money for his poetry festival. Yurlady's family uses Óscar's kindness for charity. And you begin to wonder if Yurlady isn't just stringing them all along to do the same with the knowledge that she's being bribed by people a lot more well off than her. It can only end badly for everyone as a result. Eventually this using and abusing will reach a breaking point.

Soto understands this reality is perfectly suited for drama and comedy. Especially where it concerns a lifelong screw-up like Óscar finally turning things around only to find himself in an even worse nightmare than before. Because he does truly care about Yurlady and poetry. More than Efraín. More than the Danish financiers looking to bolster their karmic portfolio. And we know Yurlady truly appreciates what Óscar is doing despite not fully being on-board due to youth and disinterest. Talent doesn't create passion. Passion doesn't create talent.

That's the main contrast point here. Óscar so wants to be the best in his field that he's martyred himself into believing he's been unfairly maligned rather than mediocre. Yurlady writes as a hobbyist outlet for her emotions, but she's not going to turn down the chance to profit off that expression to help her family survive. Put these two together and you might actually Frankenstein a single poetic icon. Separately, however, they must find the courage to admit their truths instead. Because pretending only leads them down a very dark road of destruction.

Thankfully, it's comically dark. Otherwise, the presumptions arising from a celebration turned inebriated farce would color everything in a much more traumatic light. Soto nicely allows that fact to still influence his characters' actions (Yurlady's family wanting Óscar's head) without compromising the humorous tone he's instilled from the start (but they call for it while eating the food he shameless stole from the gala to give them). Efraín is a blowhard opportunist, but he's correct about one thing. Hurt people often do just hurt themselves.

A Poet is therefore a learning experience through fire for its two leads. Óscar will see his entire world crumble to recognize his limitations and Yurlady will discover weaponizing her talent may come at the cost of her own happiness. Both Ríos and Andrade fantastically portray the melancholy born from getting in their own way and share a wonderful comedic timing of action and expression to ensure their two-pronged parasitic relationship is symbiotically drawn. The world may see them as a joke and pawn, respectively. But they still see the other's humanity.

7/10

Pulled from the archives at cinematicfbombs.com.

Dear Evan Hansen screened on September 9, 2021 at TIFF.