Week Ending 11/14/25

What came before

One of my favorite (and easiest) ways to visit films I've never seen before is by catching them before I watch a new release that connects to them. It's a built-in mechanism to not have to deal with the anxiety of picking and choosing between the thousands of classics I've missed in my life. So, if a new Wolf Man comes out, I'll fire up the original first.

Well, my dedication to this process is going to be tested in the next two months because a lot of FYC titles fall under this distinction. As you'll see below, I've started the queue by using Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein as an excuse to watch James Whale's 1931 adaptation. As a result, however, I also realized how far from the source text most versions of Mary Shelley's novel are. So, I'm listening to an audio recording of her text before GDT's film too.

Others on my list:

• Akira Kurosawa's High and Low before Spike Lee's Highest 2 Lowest

• Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless before Richard Linklater's Nouvelle Vague

• Paul Michael Glaser's The Running Man before Edgar Wright's remake

• Héctor Babenco's Kiss of the Spider Woman before Bill Condon's remake

• Ne Zha before Ne Zha 2

• Jang Joon-hwan's Save the Green Planet! before Yorgos Lanthimos' Bugonia

There are probably more I'm not even thinking about. And that's not counting a rewatch of 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later before finally seeing 28 Years Later as well as a rewatch of Zootopia before Zootopia 2.

I have my work cut out for me!

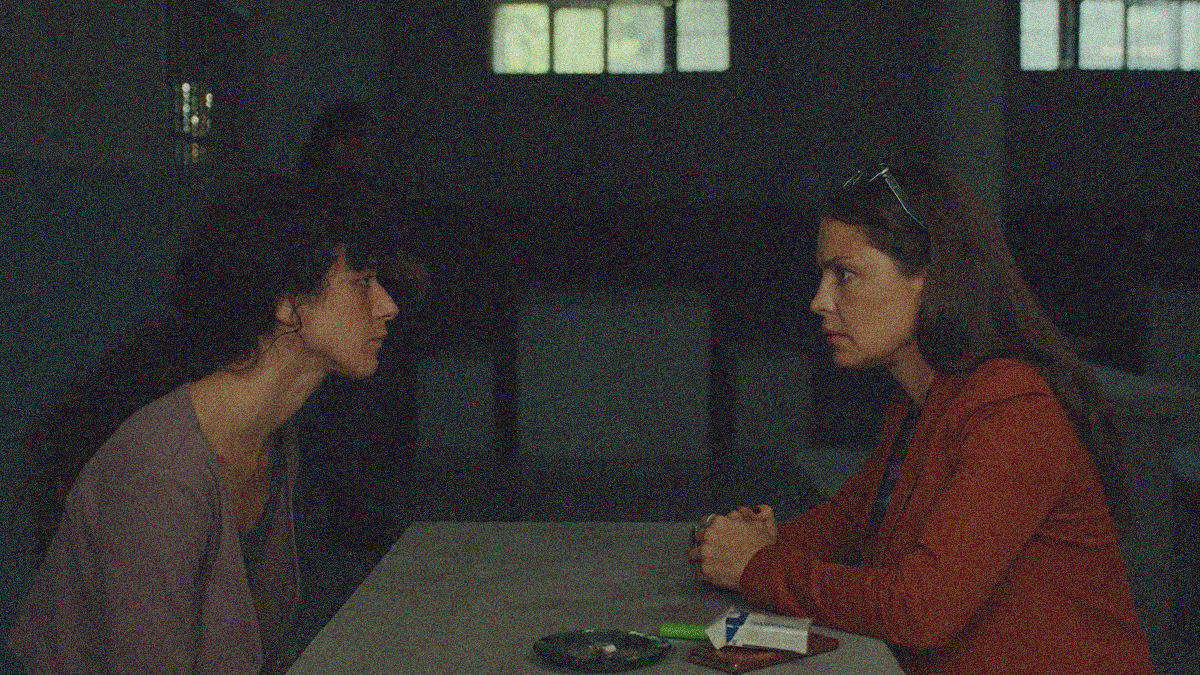

Belén

The opening scene of Dolores Fonzi's Belén (adapted by the director and Laura Paredes from Ana Correa's Somos Belén, with assistance from Agustina San Martín and Nicolás Britos), ensures that we always know the truth to what happened that fateful night in the hospital. Whereas a television show's cold open would omit certain moments to create ambiguity as far as whether Julieta (Camila Pláate) committed the infanticide for which she's accused (and been held without evidence for two years), the film's point is that it was never a question.

Not only is she not showing, but the doctor on call practically rips her tight jeans down to see her bare abdomen. Neither he nor the nurse could ever in good conscious believe she was the corresponding eight months pregnant to match the fetus found discarded in a bathroom. The injustice, however, is that both would rather say nothing so as not to contradict the police's fantasy to attach a convenient mother to the crime. They wish to strike fear into the public with one more example of the harsh carceral and social penalty for an illegal abortion.

This story is therefore made more intriguing by it not just being about the journey activist lawyers Soledad (Fonzi) and Bárbara (Paredes) take to exonerate their client. Its larger goal is to immortalize a case that inevitably helped create a sea-change for the battle to legalize abortion in Argentina and by extension grant its women bodily autonomy. We're talking the hoops jumped through to drag the case into the public's consciousness, the courage to keep fighting amidst death threats, and the ingenuity to overcome targeted bureaucratic obstruction.

The result is an effective courtroom drama that does its best to deliver a ton of context in a relatively short amount of time. We're talking precedent as far as this not being the first time Soledad took over an abortion case from the beleaguered (at best) or willfully incompetent (at worst) public defender she and Bárbara know from university (Julieta Cardinali's Beatriz). The insidious power plays by those holding authority over the law for personal or petty reasons (Luis Machín's Judge Fariña). And religious extremism played out on afternoon gossip talk shows.

There's so much going on (the involvement of Soledad's kids as weapons against her and mirrors with which to see that sea-change registering in their eyes; Julieta needing a pseudonym to protect her family from the hate people have for what they've been told she's done; the evolution of leaflets to full-blown protests taking over the streets) that the most striking bit of filmmaking courtesy of dark, blood-fueled nightmares gets lost by the wayside. Rather than enhance the drama, they feel like remnants of a different, less procedural script.

It's a tough balancing act, though. You want to give your characters the three-dimensionality inherent to the strain they are under manifesting as ticks, dreams, and stark routine, but it's nearly impossible for them to land when the pacing refuses to let the audience absorb the emotion before pivoting to another threat, another bigger picture argument (Bárbara calling out Soledad in a way that should add to their relationship, but just feels superfluous), or another comedic beat courtesy of the Sisyphean task to procure a crucial file under lock and key.

Thankfully, the messaging that one person's experience with injustice can ultimately impact an entire population always shines through. As well as the reality that our oppressors often set the table for their own demise via the hubris of believing they cannot lose. The former is critical at a time where certain states in America are making abortion illegal and thus putting every single miscarriage under a legal microscope and the latter a blueprint to remind ourselves that authoritarianism and the patriarchy aren't impervious to sustained pressure.

You must only find those willing to put everything on the line to apply it knowing the masses will follow if the mission can break through countless layers of containment facilitated and condoned by the government, churches, and media. Because a moment like Soledad debating idiots-with-an-agenda on TV may keep those who laugh at feminists laughing, but it also gives those too defeated to think trying matters proof that they wouldn't be alone in the attempt. Belén's arrest is this firestorm's match, but Soledad's indefatigable effort supplies the oxygen.

7/10

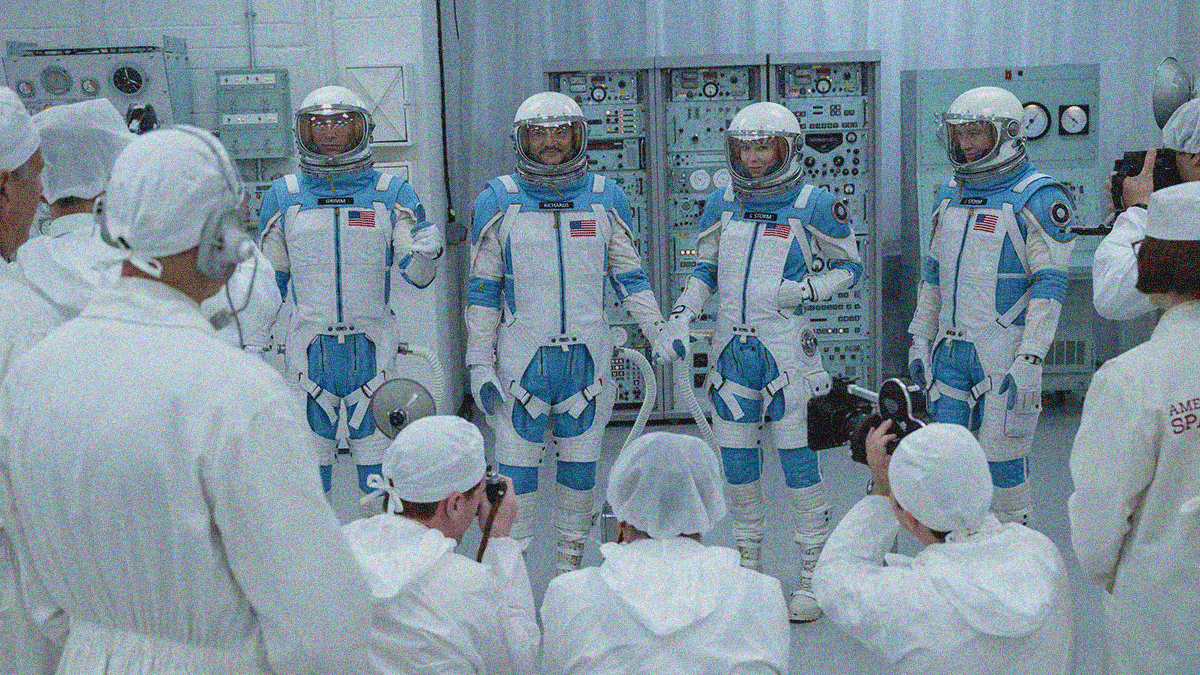

The Fantastic Four: First Steps

I’m all for style over substance and emotional impact over narrative depth, but The Fantastic Four: First Steps is very much a gorgeous toy that sufficiently distracts us for two hours before we realize nothing happened.

The plot? How can we work together as a planet to punt a villain that appears to be able to make Thanos look like a speed bump into a later "Phase"? The purpose? To integrate the titular heroes into the MCU with a nostalgia bomb that will transport fans who read the comics in the 1960s back to their childhood. The draw? My God, the production design is impeccable straight on through to the cartoon jingle post-credits.

For a film trying hard not to be an origin story (a succinct TV recap gives the highlights), it’s still a prologue doing little beyond introducing its characters. There’s still enough drama via Reed’s utopian solutions always having the fatal flaw of coming to fruition without full knowledge of the problem (the same can be said about his and Sue’s son), but I’m ready to tune in next week for more adventures … not wait seventeen months.

Great cast. Fun score. Awesome aesthetic. Very on-the-nose political Kumbaya ethos. Good CGI for Galactus. Ok CGI for Silver Surfer. Horrible CGI for the baby in a pivotal moment where it seems possible to just use the real baby. Extremely bad uncanny valley vibes for Franklin’s big coming out party.

7/10

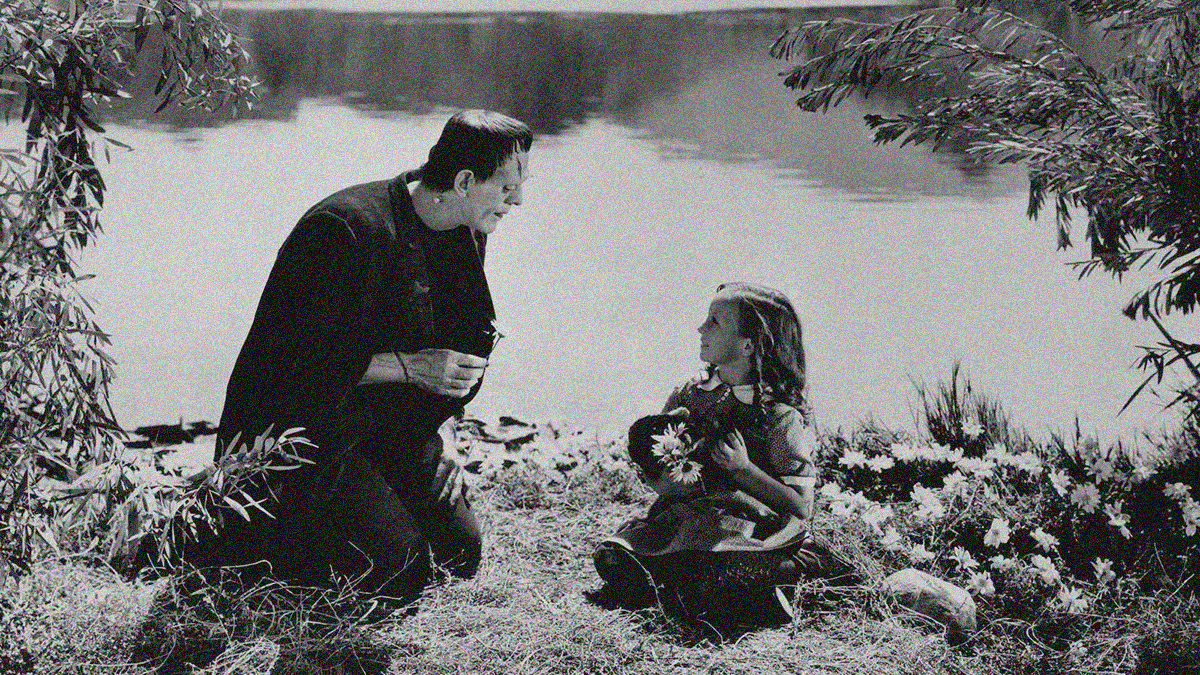

Frankenstein

This being an adaptation (by Garrett Fort and Francis Edward Faragoh) of an adaptation (John L. Balderston's American play) of an adaptation (Peggy Webling's British play) of an original novel (by Mary Shelley) is very funny to me. A beast cobbled together from numerous echoes to frighten audiences the world over.

Love the staged "warning" by Edward Van Sloan to set the mood. Love the opening title card credit for "The Monster" just being a question mark (its post-film reprise adds in Boris Karloff’s name). Love that you can see the wrinkles in the night sky curtain hanging behind the action during the townsfolk’s climactic hunt.

It’s difficult not to project all the homages I’ve seen from The Monster Squad to Phil Hartman’s iconic "Fire bad!" skit via "Saturday Night Live" onto the real deal, but the artistry, themes, and emotions still shine through this pre-code classic.

Henry Frankenstein’s creation never asked to be born. And while it’s convenient to imagine his inevitable violent streak was the result of an "abnormal brain," we all know fear and ego were the true culprits since the mob never batted an eye at their own violence. We can only hope the "next son of Frankenstein house" will be given the parenting necessary to finally be better than his self-aggrandizing father.

7/10

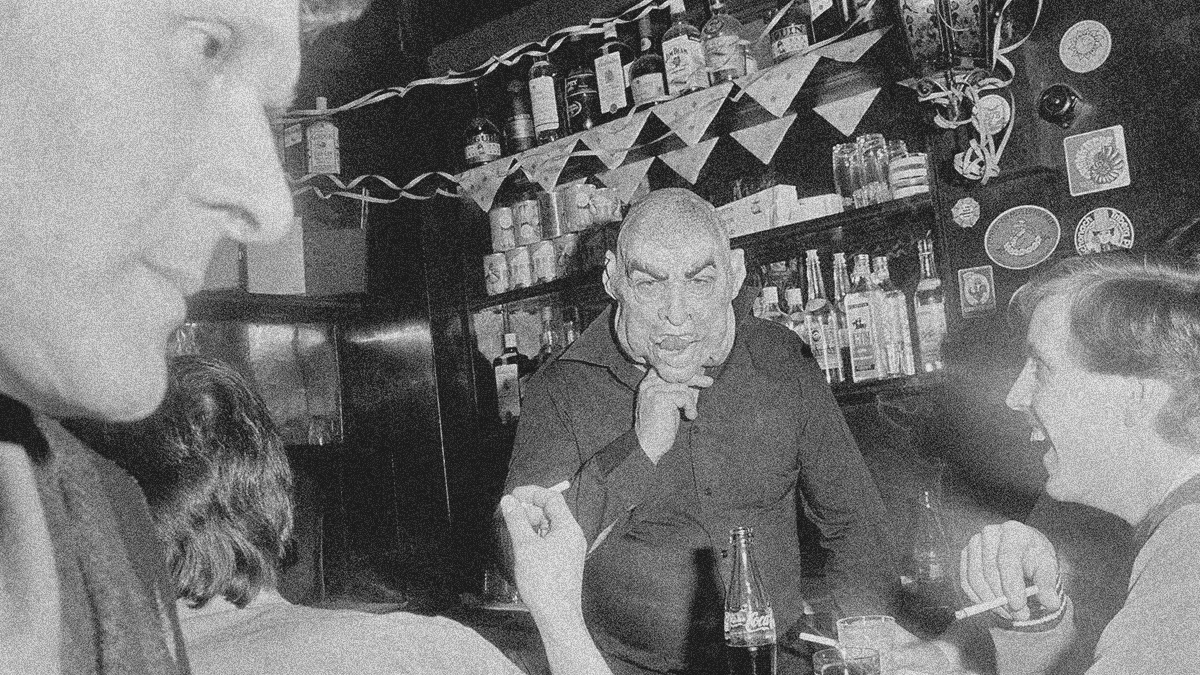

I'm Not Everything I Want to Be

While it might have taken fifty years to finally receive the recognition she deserved, Libuše Jarcovjáková always knew she was a photographer. It didn't matter that her artist father never understood the worth of her work. Nor that the people she showed her photos to would always compliment her technique while denigrating her message by saying she had none. Jarcovjáková stuck to her ambition to capture the mundane and photograph the everyday. No matter where she went or how she survived, a camera remained in her hands.

How many photographs did Jarcovjáková take? Well, director Klára Tasovská explains that it took two full years of "daily work" to organize the extensive archive of prints and negatives before crafting what would become I'm Not Everything I Want to Be. Because the entire film is told via these images and Jarcovjáková's voice reading from a script describing her life from Tasovská and Alexander Kashcheev that was inspired by her diaries. We watch her evolution, a Communist takeover, and the celebration of its fall.

What start as self-portraits and personal documentation are therefore quickly transformed into historical artifacts. Jarcovjáková brings us into a print factory to capture the life of workers on the job and blowing off steam at night—so candid that the Communist party who ran the press forbid her from taking more. She takes us to Japan to provide a juxtaposition of a bustling city like Tokyo against her dark and solitary glimpses of Prague. And her desire to leave one totalitarian prison ultimately brings her to the outskirts of another via the Berlin Wall.

Amidst these moves we learn about the methods she was forced to exploit. A travel visa against her husband's wishes that would be confiscated after overstaying its term. A paid marriage to procure another only to discover how different and isolating European capitalism was to life under Soviet rule. We meet the two men she married for utilitarian purposes and the women she loved with true passion. And from that duality comes the discovery that art intended to champion her friends' lifestyles could be weaponized against them.

The political ramifications of her work is therefore paramount as far as its context to the era. Yes, that entails the machine of labor and power to which Jarcovjáková was a victim, but also to the constraints of gender, sexuality, and progressivism. So, there are shots of lovers in differing stages of undress alongside rebellious graffiti and hand-scrawled signs of defiance. There are portraits of working-class men and women in Prague, Tokyo, and Berlin alongside the lucrative marketing promos that paid her well but always felt hollow.

This autobiographical account of Jarcovjáková's life and world around her is captivating enough, but Tasovská knows ninety-minutes of still photos and a single voice demands kinetic energy to keep our attention. So, she uses lighting effects and quick cuts to bring the static shots to life—strobing between alternate takes as though a flip book set to music and brought to life. Sometimes she tiles images to create progression within a single event. Other times see her repeating one image to crudely animate a figure moving across the screen.

It's an informative and exciting piece that provides the parallel journeys of political oppression and individual awakening. The title epitomizes this notion by portraying its subject in flux and searching for who and what she does want to be outside of the demands of authoritarian regimes. Jarcovjáková admits she'll probably never be fully satisfied, but the rapid montage of images between her return to Prague post-USSR and her 2019 Arles exhibition show us a woman and artist as close to being everything she'd hoped as she'll allow.

7/10

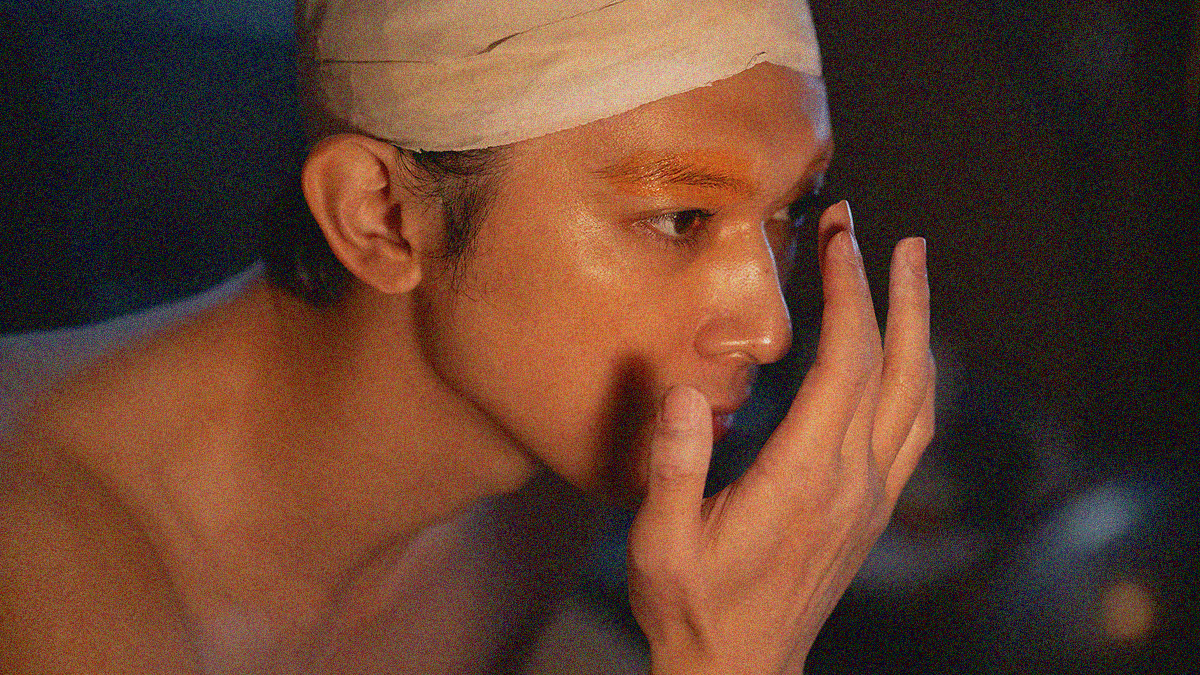

Kokuhô

Famed kabuki actor Hanjiro Hanai (Ken Watanabe) accepts the hospitality of a Yakuza leader (Masatoshi Nagase's Gongoro Tachibana) in Nagasaki when his latest show passes through. With it comes an invitation to the infamous man's annual New Year's Party where his own son (Soya Kurokawa's Kikuo) would perform as the centerpiece play's onnagata (female role played by a man). So taken by the performance's emotion, Hanai presumes a geisha is on-stage. Gongoro is proud of his son and pleased to correct the error.

More than just a chance encounter, however, this occasion proves the genesis of the rest of Kikuo's life once the Tachibana clan is attacked at the conclusion of the play. The teen's stepmother implores him to run and hide, but he wants only to stay and defend his father. Hanai helps to hold him back as they both watch Gongoro live up to his fearsome reputation. He might have even taken them all out with his katana if not for an intruder's gun. So, as his father yells for him to watch his victory, Kikuo inevitably watches his death instead.

Director Sang-il Lee's Kokuhô, adapted by Satoko Okudera from Shûichi Yoshida's novel, soon fast-forwards and shifts setting to Osaka. It's there that Hanai's family lineage has taken root and prospered with an acclaimed theater and school where he trains his own teenage son (Keitatsu Koshiyama's Shunsuke) to follow in his footsteps. Much like with the Yakuza, heritage and bloodline rule the kabuki scene. The art form is passed down through the generations with a succession of revered titles. Shunsuke will be Hanai's heir and Kikuo will be his apprentice.

Lee was previously interested in kabuki as a subject for film but could never quite find a way to do it. Every attempt to write around an actual actor's biography didn't get him where he wanted, so he pushed the idea aside until reading Yoshida's novel (Lee previously adapted his book Villain). He took the story and found a way to bring it to life by focusing on Kikuo's rise from Yakuza orphan to kabuki celebrity and the tragedies, betrayals, and deceit endured and ignited along the way. Lee only had to find an actor capable of carrying the role.

Because it's not long before these teenaged amateurs grow into a performing duo with the pedigree to hit a blockbuster stage earlier than most. Lee chose specific kabuki plays that aligned thematically with the boys' evolutions—providing the title of each in Japanese characters along with a description in English for those of us unversed in the art's canonical entries—for them to perform. So, Ryô Yoshizawa (Kikuo) and Ryûsei Yokohama (Shunsuke) not only needed to act their characters' real-life drama, but their onstage dancing too.

Kokuhô is epic in length at almost three hours, so you can assume things won't be as copacetic as they are during Kikuo and Shunsuke's initial run. Yes, they are living up to the potential of the "Hanjiro" moniker and their shows are selling out, but there's still the matter of both living under a shadow that possesses the room for just one successor. Will it be the son who was destined and groomed to take over from birth? Or the objectively more talented apprentice taken under wing? Which is more important to Hanai's legacy? His blood or his art?

You can ask the same question about Japan's legacy considering Kikuo's origins as the son of a criminal whose back tattoo ensures nobody will forget. What happens when Hanai's shield of legitimacy goes away? In a perfect world, audiences and benefactors will show loyalty to the craft and accept this outsider. After all, every lineage must start from somewhere since you'll eventually hit an ancestor whose father didn't train them. Humanity is flawed, though. An inspiring tale of a reformed Yakuza quickly transforms into one of a conniving thief.

And it's not just Kikuo's star losing its luster. It's also Shunsuke reckoning with the reality that his blood didn't make him the best. That all the time and effort to live up to his father might not have given him the one thing he needed to succeed: a love for kabuki itself. There's a difference between being good at something and enjoying it. Whereas Kikuo yearns to improve for his own sake, Shunsuke's more relaxed partier enjoyed making his father happy and fooling around on-stage with his best friend. One fought to be something. The other was by default.

What's really captivating about the film, however, is that these parallels and contrasts are never steeped in jealousy. Kikuo and Shunsuke are brothers by every definition besides biology. They do genuinely want the best for the other and can't even pretend to be angry when the other takes what they assumed was theirs for longer than a second before admitting it would actually be easier if they could hate one another. We're instead watching the complex machinations behind trying to honor where you came from while also cutting a path for yourself.

Lee takes us from the 1970s all the way to the 2010s, so there are as many periods of struggle and separation as there are camaraderie and joy. Both men make horrible mistakes when choosing between themselves and their fates. Both men leave loved ones in tears while exploiting their positions or those in a position to be an asset to their goals. None of the women are treated particularly well whether Shinobu Terajima, Mitsuki Takahata, Ai Mikami, or Nana Mori. Hanai, Kikuo, and Shunsuke all hold kabuki as their one true love instead.

Add a "deal with the Devil" and an aging onnagata gatekeeper (Min Tanaka's Mangiku) and Kikuo's journey is rife with ups and downs thanks to his heritage placing a ceiling on the heights his talent deserves. It's not fair in a general sense, but one could argue it's also a karmic necessity considering the lives he hurts to reach that pinnacle. The most interesting characters are often those with the most flaws and Kikuo has plenty. Kokuhô, however, does not thanks to a great cast, impeccable direction, and poignant kabuki plays to tie it all together.

8/10

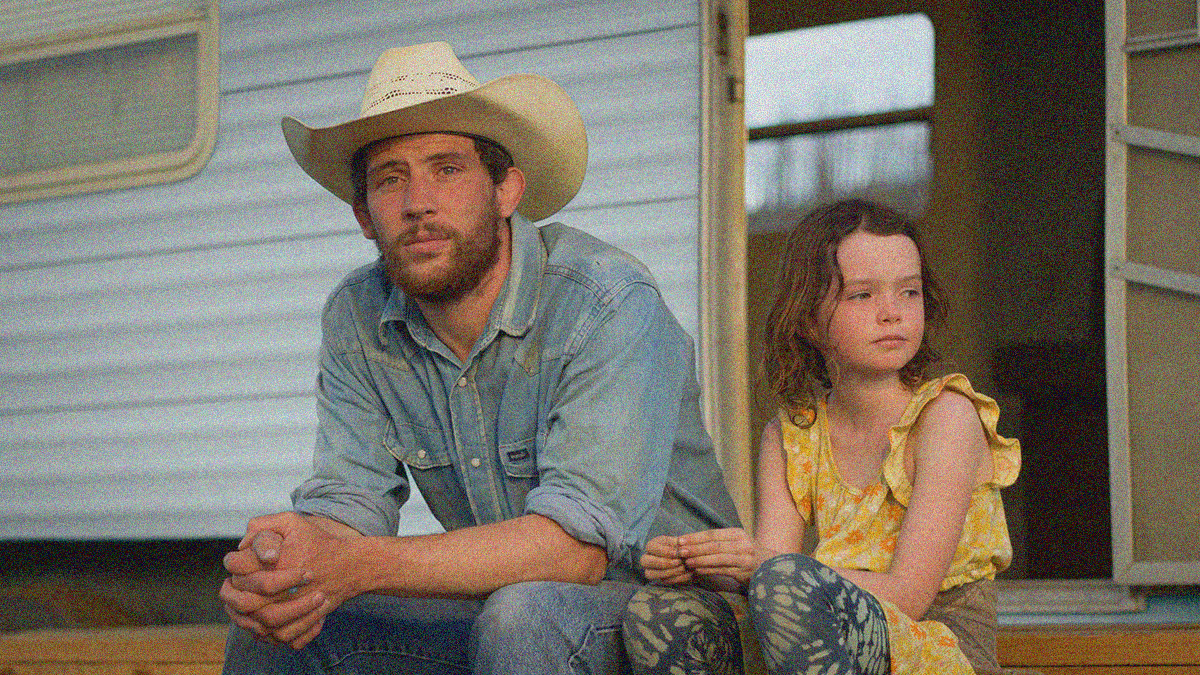

Rebuilding

Writer/director Max Walker-Silverman says it best when describing his latest film, Rebuilding. "This is not a disaster movie. It's about what happens after." It's why the first thing he shows us is the ash in the air. Because it's not that a fire might hit Dusty's (Josh O'Connor) home. It's the inevitability that fire has already arrived. From there it's the charred remains of a small ranch's foundation and the barren trees surrounding it. Then Dusty straining to remember what had been for generations, uncertain of where this tragedy takes him next.

We, like this cowboy, assume the title alludes to a return to normalcy. That Dusty will collect insurance money, get a loan, and put his life right back where it was before the flames came over that hill. But that's not how this works. Because any money that might come won't arrive any time soon. Government assistance is about providing a temporary respite that is purposefully not constructed to last. And the land is toast where hopes of bringing livestock back in to graze is concerned. So, his best bet is to pack-up and leave Colorado behind.

Enter Callie-Rose (Lily LaTorre), Dusty's daughter. She hasn't seen much of her father since he and her mother (Meghann Fahy's Ruby) split. Not because of any animosity or intent. Life on a ranch by oneself due to an inability to hire help is simply untenably busy. The girl is therefore unsurprisingly distant—assuming this latest visit is a fluke before another lengthy spell apart. But when she realizes it's the opposite? That Dad's listlessness means availability? She brightens right up. She looks forward to seeing him and hopes to turn his new trailer into a home.

It's this vehicle that becomes the linchpin to Walker-Silverman's narrative. He utilizes what it represents to Dusty (a stop-gap remembrance of what he lost) as a means of showing mankind's stubbornness to evolve out of that which they've only ever known. And he juxtaposes that with what it represents to Callie-Rose (an opportunity for rebirth) as a means of introducing the true object of the title's action: their relationship. Her innocent question, "Can you still be a cowboy without cows?" actually asks, "Are you a father if you're never here?"

Born from the filmmaker's own experience living between his parents' separate homes when his sister lost hers to fire, Rebuilding feels authentic from the first frame. Walker-Silverman understands these circumstances. He knows the risk of destruction too many can't escape due to how intrinsically connected their lives are to their livelihood at a moment when the effect of global warming is no longer a question to consider down the road. And he also acknowledges its potential to force a necessary reconsideration of one's priorities.

Dusty is so caught up in what he thinks he needs that he refuses to see what he has. This trailer? It's not real. His new neighbors (who also lost everything to the fires) like Mila (Kali Reis) and Art (David Bright)? They're just strangers. Because he's going to get back on his feet. His land is still there. He'll make it better than before, even if it means leaving for Montana to earn the money to do so. He's blinded by this identity that he projects upon himself as a rancher before his identity as a father. Maybe, if he's paying attention, he'll realize he's wrong.

The evidence with which to get him there is all around him. Mila actually losing something she can never get back. Ruby's mother (Amy Madigan's Bess) reminding Dusty that nothing is truly forgotten if you're willing to remember. A community enduring the same hardships as him while still making the best of it because they'll do whatever they must to stay together (the scenes outside the library to use its Wi-Fi are both heartbreaking and beautifully poignant). Dusty has been so desperate to survive alone that he's forgotten he's not.

Kudos to Walker-Silverman for never falling prey to the impulse to inject romance (either rekindled with Ruby or ignited with Mila) because it would prove counterintuitive to its message about looking inward to move forward. The love on display (besides that connecting Dusty to Callie-Rose) is platonic. It's empathetic in the face of universal struggle. How do we come together to not only rebuild ourselves, but our humanity away from the constraints of a capitalist system built to discard the exploited majority as another expendable "resource"?

There's a healthy dose of hope at the back of Rebuilding as a result. That through its never-ending tragedy lies the reality that people, not possessions, make a home. That what you do isn't as important as who you are. Ruby, Bess, and Mila understand this fact. They might not know what the future holds, but they know what they won't compromise along the way. That's what Dusty must discover and O'Connor's brilliantly understated performance moving from lost soul to renewed purpose shows it's never too late. Life endures.

8/10

The Things You Kill

I was awed by the moment. Ali (Ekin Koç) is seen inside the hut overlooking his garden when the camera finds a broken mirror hanging by the door. It's through its reflection that we then watch Reza (Erkan Kolçak Köstendil) approaching from the field with a request for water. When Ali complies and takes the bottle from his hand, the camera pushes in farther to remove the mirror's frame. And, almost imperceptibly, the blemishes upon the glass fade while the lens continues its pan ... back to the mirror. We've impossibly escaped reality's constraints.

It's a gorgeous piece of filmmaking on writer/director Alireza Khatami's part both because of its visual intrigue and its ability to explain that which we don't yet know needs explaining. We shouldn't be surprised by the latter, though, considering The Things You Kill begins with Ali's wife Hazar (Hazar Ergüçlü) relaying a strange dream she had about his father. This veil between perception and knowledge is present throughout the film, so Khatami actually wants us to interpret that shot differently. We didn't escape the mirror. We entered it.

The entire film is built upon these complex reflections of ourselves. Whether it be our present in relation to the past and/or future or our identity in relation to our parents and/or children, our entire lives become echoes of what was and what might be. It therefore falls on us to choose how this truth impacts our own personal journeys. Will we reject our problematic heritage and destroy it to be better? Will we become victims to its never-ending cycle? Will we believe we're doing the former only to realize it's just a different form of the latter?

These are the questions Ali doesn't even know he's asking because he's tried so hard to forget their presence. He's a man at a crucial crossroads wherein the contradictions of his life can no longer be ignored. The why of leaving Turkey to study abroad in America. The why of returning home. He needed to get away from his domineering father (Ercan Kesal's Hamit) to neither become him nor kill him. And he needed to come back to his mother (Güliz Sirinyan's Sakine) to make up for not being able to protect her from him in youth.

Ali must now also worry about his own desire to start a family. To finally see if his father's violence exists within him. Since he now has the confidence to stand up to his dad and call out his misbehavior, his fear shifts to an uncertainty in having the wherewithal to call out his own. So, what is the real reason he neglects to tell Hazar that his sperm count is preventing them from conceiving? Yes, it's an intrinsic sense of toxic masculinity and an inability to be vulnerable. But it's also an excuse to avoid his worst fate.

Avoidance is hardly better, though. Bottling your emotions inevitably ensures they'll come out uncontrollably later. So, as Ali struggles to reconcile who he might become with who he hopes to be, he heads towards an inflection point. To not have a baby means never being a bad father, but what if telling Hazar he doesn't want one means he won't be a husband either? Then there's also being a law-abiding citizen versus bending the law for an advantage. Can he still demand accountability from others if he can't hold himself to account?

That brings us to Sakine's death and the many questions that surround it thanks to what Ali knows and what his sisters have been hiding from him at her behest. If the themes of patriarchy weren't already evident, they will be now as we witness how much these women have been conditioned to accept and how much a man's ability to be heard within that system can allow his good intentions to evaporate with one bad impulse. Is Hamit a bad man regardless of his own trauma making him that way? Yes. Enough to kill his wife? Maybe.

It's a question Khatami intentionally doesn't answer. The fact Hamit's son believes it to be true is enough. But the filmmaker also doesn't fully answer what happens next once Ali enlists Reza to help seek revenge. Because we entered the mirror and all bets are off as far as objectivity is concerned. Figures in dreams are just as easily explained as ghosts if the search for meaning is replaced by the nightmarish potential of instinct. All we know for sure is that Ali considers embracing his urge for violence. Does he get lost in its rage? Or does it remind him why he can't?

While everything that occurs within The Things You Kill does so with purpose, so too does everything outside of it. Namely your confusion when a character inexplicably takes the form of another. Think David Lynch's Lost Highway, but en route to a possibility for redemption rather than pure oblivion. Khatami needs us off-balance to accept the actions Ali commits post-transmutation. It allows us to recognize his path's divergence and still hope he might fight the craving to give into the darkness. The puzzle comes into focus when he makes his choice.

It's a stunning piece of cinema that gets beneath the surface of an all-too familiar story to give form to the universal psychological struggle at its back. Because this isn't a Muslim problem or Evangelical problem. It's a human problem. The patriarchy exists wherever society demands its specific brand of gender norms are baked into the very laws that govern it. Khatami wrote the film to be set in Iran only for the government to demand he remove a crucial event, so he shifted to Turkey instead. It would have worked just as well in America too.

9/10

This week saw American Exit (2019) and Dream a Little Dream (1989) added to the archive (cinematicfbombs.com).

William McNamara dropping an f-bomb in DREAM A LITTLE DREAM.

Opening Buffalo-area theaters 11/14/25 -

• The Carpenter's Son at Regal Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Christmas Karma at Regal Elmwood

• De De Pyaar De 2 at Regal Elmwood

• Hidden War at Regal Transit

• Kaantha at Regal Elmwood

• Keeper at Dipson Capitol; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• King Ivory at Dipson Capitol; Regal Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Muzzle: City of Wolves at Regal Transit, Quaker

• Now You See Me: Now You Don't at Dipson Flix, Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge, Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• The Running Man at Dipson Flix, Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge, Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Santhana Prapthirasthu at Regal Elmwood

• Trap House at Regal Elmwood, Transit

• Wicked (Re-Release) at Dipson Amherst, Flix, Capitol; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

Streaming from 11/14/25 -

• Belén (Prime) - 11/14

Thoughts are above.

• Come See Me In The Good Light (AppleTV+) - 11/14

• Eddington (HBO Max) - 11/14

• In Your Dreams (Netflix) - 11/14

• Lefter: The Story of The Ordinarius (Netflix) - 11/14

• Nobody 2 (Peacock) - 11/14

• Nouvelle Vague (Netflix) - 11/14

• One to One: John & Yoko (HBO Max) - 11/14

• A Very Jonas Christmas Movie (Disney+) - 11/14

• Osiris (Hulu) - 11/15

• Selena y Los Dinos: A Family’s Legacy (Netflix) - 11/17

• Thoughts and Prayers (HBO Max) - 11/18

• The Carman Family Deaths (Netflix) - 11/19

• Champagne Problems (Netflix) - 11/19

• Preparation for the Next Life (MGM+) - 11/19

• The Son of a Thousand Men (Netflix) - 11/19

• The Follies (Netflix) - 11/20

• The Roses (Hulu) - 11/20

Now on VOD/Digital HD -

• Beyond the Gaze: Jule Campbell's Swimsuit Issue (11/11)

• Deathstalker (11/11)

• Drive Back Home (11/11)

• Frenzy Moon (11/11)

• The Gangs of Paris (11/11)

• The Guardsmen (11/11)

• Kiss of the Spider Woman (11/11)

• Mr. K (11/11)

• Orwell: 2+2=5 (11/11)

• Queens of the Dead (11/11)

• Roofman (11/11)

• Ruthless Bastards (11/11)

• Soul on Fire (11/11)

• Under the Stars (11/11)

• The White Mountain (11/11)

• Dashing Through the Snow (11/13)

• Dog Patrol: Operation Santa Paws (11/13)

• Are We Good? (11/14)

• Citizen Sleuth (11/14)

• Diario, Mujer & Cafe (11/14)

• Murder at the Embassy (11/14)

• One Battle After Another (11/14)

"Anderson knows how to make a three-hour runtime entertaining and every second DiCaprio and Del Toro are on-screen together is a gift from God. [But it] is one very good film that might have been three great ones." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• The Perfect Gamble (11/14)

• Run (11/14)

• Tatsumi (11/14)

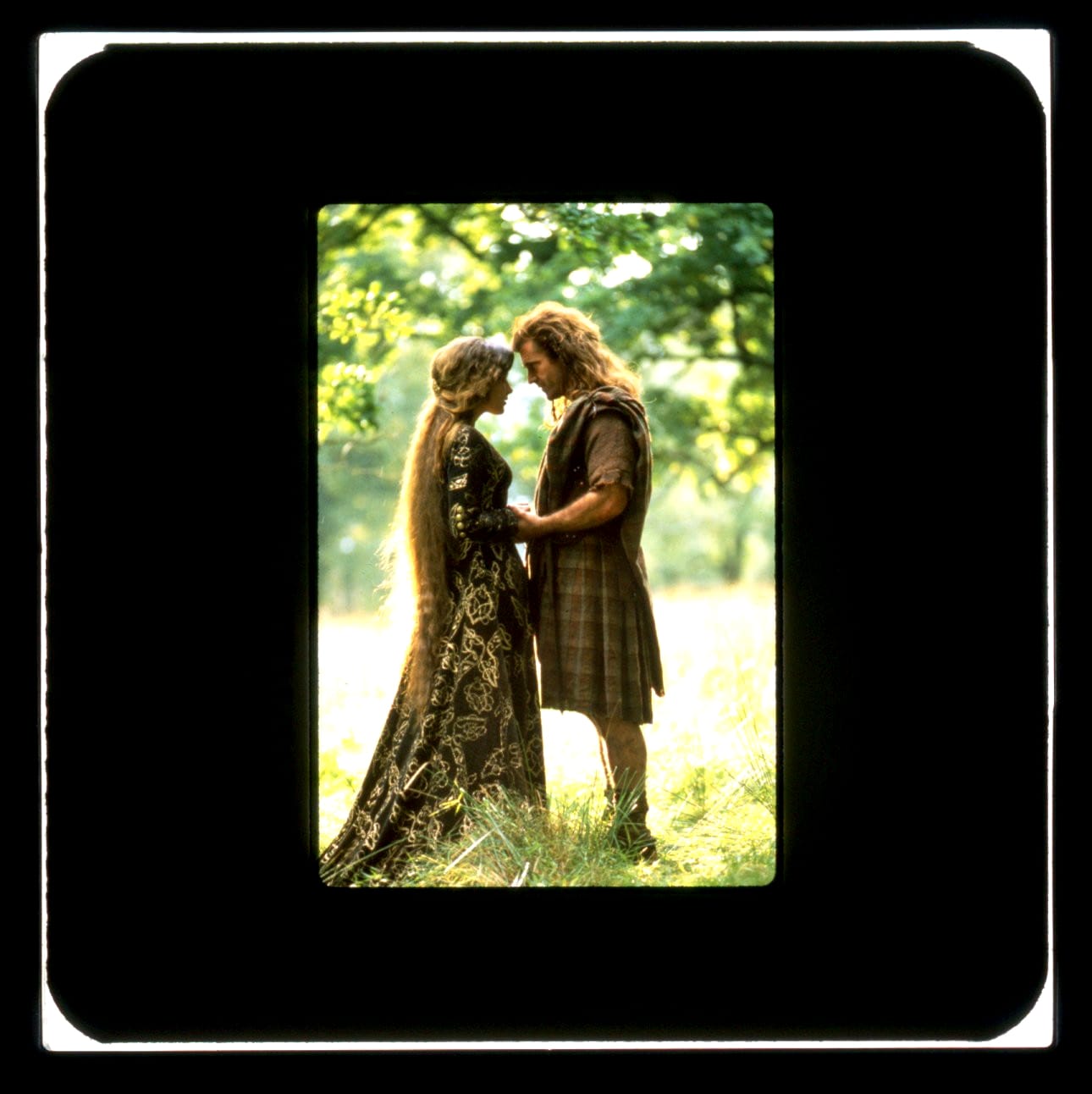

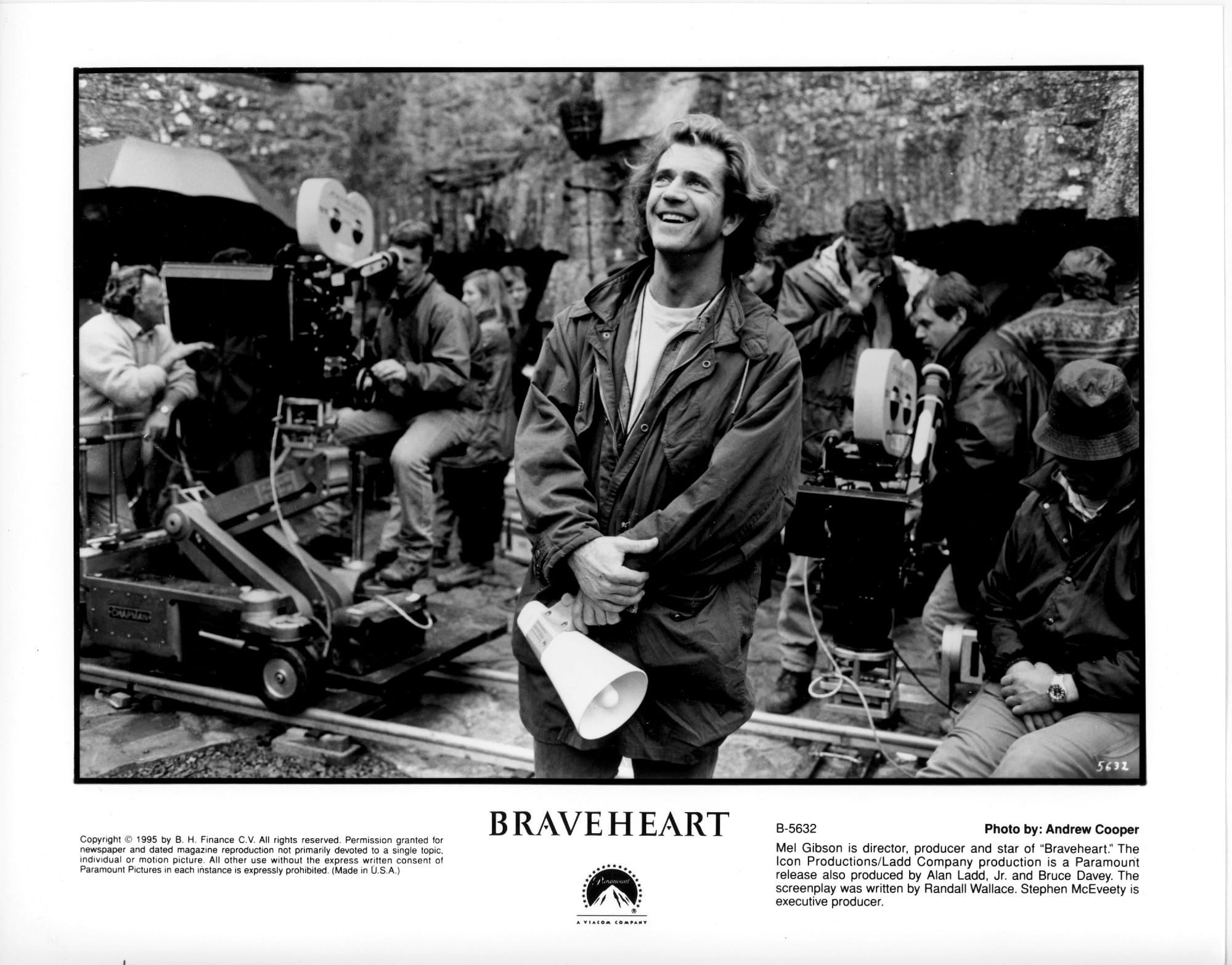

Pieces from the Braveheart (1995) press kit.