Week Ending 12/12/25

2025 in music

Today's new releases are going to put a pin in 2025 for me as far as music is concerned. My "Need to Listen" playlist is winding down after adding a bunch more this week courtesy of some Top Albums of the Year lists (I hadn't listened to about two-thirds of the Pitchfork Top 50, but had listened to about three-quarters of the Rolling Stone Top 100 ... go figure).

It's a been a transition year as far as keeping track of albums and listening to songs too. I started using the Echo app to catalogue completed albums so I don't wind up thinking I missed something I didn't. And we switched our household streaming subscription over from Spotify to Qobuz. I need to play around with embedding playlists from the latter to my website, so I may still be using the former for that.

The majority of tracks for my annual two-disc mix are purchased and ready to sequence. I'm still leaving a couple in the air in case a dark horse contender arrives at the eleventh hour—it does tend to happen. Just yesterday I listened to Brian Dunne's Clams Casino and CMAT's EURO-COUNTRY for the first time and both were good enough to give me pause about grabbing a song.

So, once I get the order set and jackets designed, I'll get to printing physical copies for friends and family and putting a webpage up to share with everyone else. The header image above gives a sneak peak at some of the artists included.

Dust Bunny

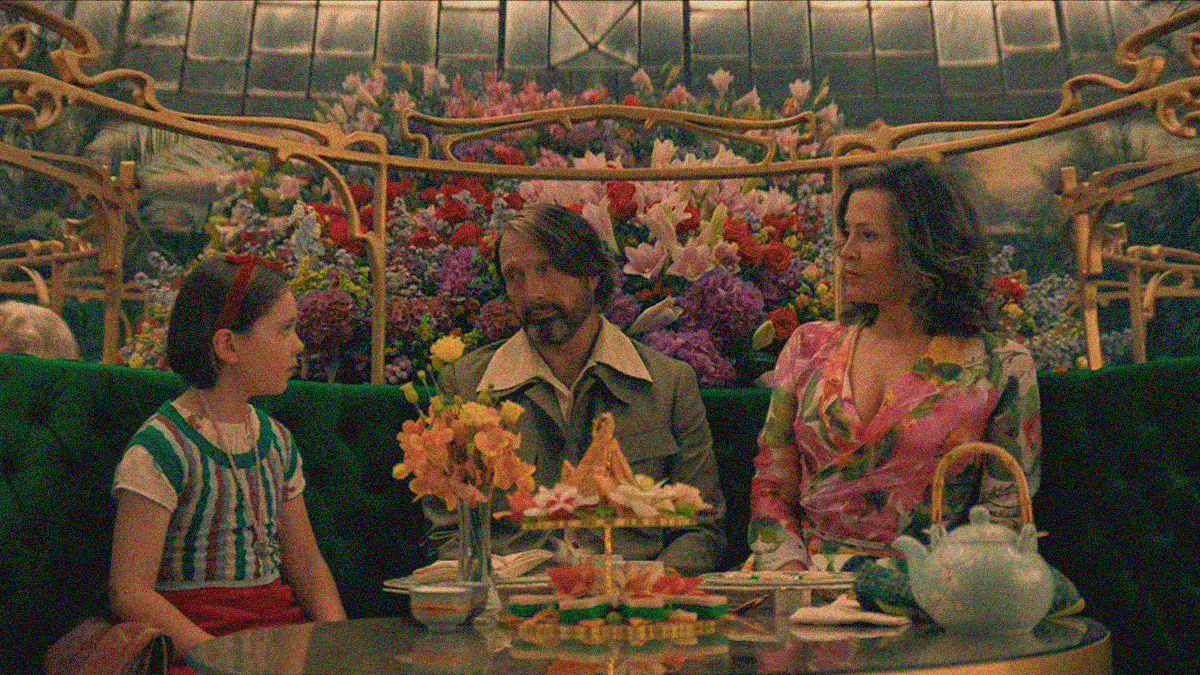

If you told me the plot of a new film about a little girl who tries to hire her mysterious neighbor to kill the monster under her bed that ate her parents, I'd ask who Lee Pace was playing because it sounded like something Bryan Fuller would conjure out of his singular imagination. Well, since that is exactly what Dust Bunny is about, I'd be half correct. Fuller is the brain, but Pace isn't the brawn. No, he gave the Pie Maker (or Aaron Taylor, if you prefer) time off for this one and enlisted his Hannibal Lecter to come aboard instead.

Why does Aurora (Sophie Sloan) think her Intriguing Neighbor (yes, that's Mads Mikkelsen's character credit) can get the job done? Because she's seen him do it before. This girl has dealt with the beast rising from the floorboards any time she touches her apartment floor many times. She's desperate for a solve and her neighbor's shady schedule keeping him out during the night before coming home a bit worse for wear seems to fit the bill. So, she follows him to Chinatown one night and watches him slay a dragon with her own two eyes.

Or did she? We know the truth because Fuller reveals it. While Aurora watches shadows on the wall of her neighbor gutting a Chinese dragon, we see the reality of him beating on a group of men using said costume as a disguise. It therefore begs the question: is there really a monster under her bed? We've seen evidence that there is, but why couldn't it just be that Fuller is showing us those scenes through the girl's mind? If she believes a monster keeps her scared at night, a monster is what she sees. And if her parents are gone, well ... there it is.

This ambiguity is a feature of Dust Bunny's script. It is asking us to have faith in what Aurora is saying even if what she's saying isn't entirely true. Because regardless of the supernatural filter being used, her fear is authentic. Her desperation isn't an act. And, to her neighbor's credit, he believes this to be true—presumably from experience. Not the monster manifesting itself to consume everything in its path before leaving the floor seemingly untouched, but the idea of "monsters" threatening abuse. He wants to protect her.

He also thinks he must since he believes he's the reason this "monster" took her guardians. That they were after him and simply got the wrong apartment. He feels guilty. He admits as much to his handler Laverne (Sigourney Weaver) who in turn worries if he's gone soft. Not only is he putting himself on the line (and her by extension), but he's doing it for someone who now knows his face. Her advice is therefore to kill Aurora, pack-up his things, and leave. Live to fight (and kill) another day. Because it won't just be one monster coming for them anymore.

I truly love the way Fuller delivers nightmarish metaphor and horrible truth simultaneously so that we don't know which to believe until one of his two main characters sees the evidence necessary to change their mind. Either Aurora must see the "monster" is just an assassin looking to clean-up a mess or Mikkelsen's neighbor must see the monster to realize he's in worse shape than he thought. Add more strangers to the mix and there arrives more inconsistencies. Because if he's killing one assassin in the hall, who (or what) got the one in the bedroom?

The film proves a perfect vehicle for Fuller's dual sensibilities. The subject matter is dark like "Hannibal" and "Dead Like Me", but, thanks to a child's perspective, is absorbed through an absurdly surrealistic lens a la "Pushing Daisies" and "Wonderfalls". Look no further than Mikkelsen being Intriguing Neighbor or David Dastmalchian being Conspicuously Inconspicuous Man. Or the gorgeous shot of an assassin perfectly camouflaged by the apartment's wallpaper. Or whatever it is two FBI agents are doing sliding back and forth on a hallway floor.

Every set is meticulously designed. Big flourishes like the Chinese Dragon shadow and little ones like the animated bunny-shaped dumplings at dim sum maintain the off-kilter whimsy Fuller conjures to make heavy subject matter look lighter despite never undercutting the impact of its weight. And the cast plays it just left of natural but not quite all the way to caricature whether Dastmalchian's shadowy figure or Sheila Atim's stylish social worker. He also knows how to keep landing a good joke without it overstaying its welcome ("uh-ROAR-uh").

Beyond just aesthetic, Dust Bunny also crucially needs Sloan and Mikkelsen to carry the comedy and drama. Because this isn't merely a lark. The back story we get about both Aurora and her neighbor reveals the real horror on-screen and the lasting effect it can have on a child. Fuller gets very vulnerable in his director's statement to reveal his own experience with an abusive father and the desire to wish he'd disappeared by any means necessary. It's neither a silly fairy tale to Aurora nor a mistaken identity action flick to her neighbor. It's about survival.

That we understand this fact while still getting to enjoy two hours of high concept entertainment shouldn't be understated. Fans of Fuller's television shows won't be surprised at the effectiveness of that psychological layering, but maybe it will get new audiences to seek out a cult classic like "Wonderfalls" and realize there's meat to the superficially candy-coated bones of "Pushing Daisies". Aurora didn't choose to need a monster to do her bidding or a hero to dispatch of it once finished. But she did make that choice. And these are the consequences.

8/10

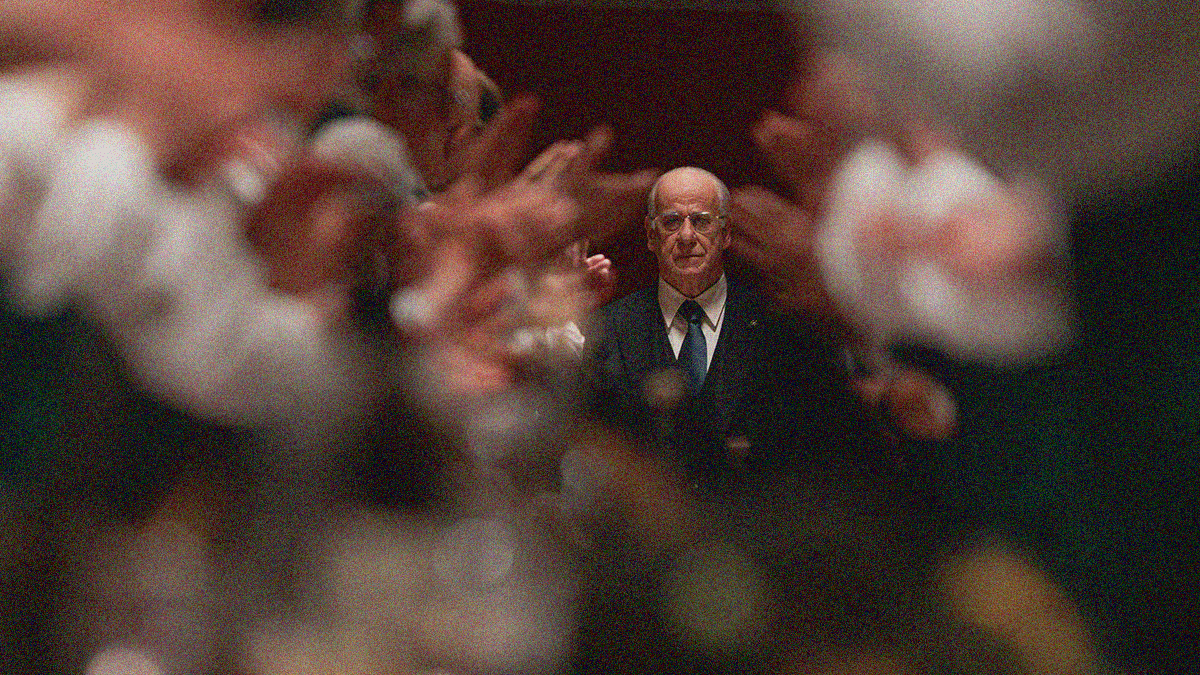

La grazia

I don't know how much of it was nostalgia for a president with integrity, but I kind of loved this. That's coming from someone who generally finds Paolo Sorrentino to be a great visualist and a messy dramatist.

An objectively smart script with a memorable protagonist (Toni Servillo is wonderful) caught in a three-quarter life crisis who's coming to grips with the too often ignored concept that progress should be embraced and stewarded by passionate men and women much younger than those often tasked with the assignment. It's also an objectively hilarious script that never ceases to surprise in its music choices, sight gags, or pointed banter.

I'm putting Milvia Marigliano in the top Supporting Actress spot of all my ballots.

8/10

Hamnet

We meet Will (Paul Mescal) and Agnes (Jessie Buckley) as pariahs at the start of Chloé Zhao's Hamnet (as adapted by her and Maggie O'Farrell from the latter's novel). He is a Latin tutor working to pay off the debt his father owes the family of the boys he teaches. She is those boys' half-sister, said to be the daughter of a forest witch and thus unsuitable for true love. It's as though fate turns their guardians into the cruel creatures they prove simply to provide both an escape through the other. To turn their pain into joy.

They did exactly that at first. Yes, they used some manipulation to earn their marriage being that neither family (especially his mother, Emily Watson's Mary, and her brother, Joe Alwyn's Bartholomew) approved of the other. But who can say no to a baby? To happiness? It's merely a shame that it couldn't last—at least not in its current form with Will continuing to lose himself to the suffering of a small life within his father's abusive shadow. So, Agnes sends him to London to write. To follow his dreams and make good on her premonition.

The first two-thirds of the film hinge on this ability to see the future of those whose hands she touches. It gives Will strength to leave knowing he'll come back. It makes their son Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) brave when having to say goodbye to his father yet again. And since you should already know the boy's destiny going in, this gift may also feel like an unnecessary flourish made false before having the chance to believe. Well, that would be a mistake. Agnes might not know the details, but her vision of Hamnet and his father in London isn't a hoax.

From the moment of Susanna's (Bodhi Rae Breathnach) conception, Hamnet more or less becomes a waiting game for the inevitable death that sparks Will to write "Hamlet." It's a beautifully shot journey that takes us through the forest from which Agnes gains her power and maintains her connection to the past (namely her late mother) to the small home where Will was born. Initial animosity between Mary and Agnes soon gives way to love and the trio of Susanna, Hamnet, and Judith (Olivia Lynes) is always ready for a laugh.

So, when the death finally arrives, it does hit with the desired potency. Be it the false start, the bittersweet yearning to trick Death, or the circumstances of where each parent is in the moment, you feel the loss as strongly as those on-screen. Even so, it was expected. It's literally the catalyst for the grief that gives birth to one of the most celebrated tragedies of all-time. My emotional response wasn't therefore meeting the level of that which I've heard considering some movie theaters are handing out tissues. I worried I've grown too cynical.

With forty-five minutes left, however, I had faith Zhao would get me there. But I admittedly didn't know how considering "Hamlet" the play has nothing to do with the experience Agnes and Will endure on-screen. Watching him write it to exorcise demons wouldn't move the needle. Repeated scenes of Agnes telling Will he can't know what she feels because he wasn't there might move it a little, but you can only perform the same dance so many times. Zhao and O'Farrell agree. There's none of the former and just one example of the latter.

How they do it is simple. "Hamlet" might not have anything to do with their loss literally, but boy does it thematically. More than just show us the parts from the play that prove it, however, Zhao goes one step further by letting us bear witness to Agnes and Will experiencing those parts for the first time themselves. The moment it clicks in her mind that he's swapped roles with his dead son was the moment everything clicked for me too. The visually and emotionally effective (if narratively familiar) drama that preceded it was all building to this.

Buckley and Mescal's death wails didn't move me to tears, but their reactions to the actors (led by Noah Jupe as Hamlet—what a coup that Jacobi also acts for this dual casting choice to sing) and each other surely did. This is how you portray grieving parents exorcising their demons. Their grief lives through the art. "Hamlet" becomes an outlet to say what cannot be said (Will) and hear what cannot be heard (Agnes). The play doesn't exploit their tragedy. It memorializes a life and ensures the entire world celebrates and mourns him with them.

Zhao is spot-on when she talks about Hamnet exemplifying the "alchemy" that can occur when one's art is wielded as a therapeutic outlet. Whether from the novel or added for the film, she and O'Farrell's metaphors and doubles (Orpheus looking back at Eurydice, the dark pit of the forest tree and the door of Will's stage, the refusal to believe in Heaven so as not to let a soul leave our memory on Earth) are planting seeds for the characters' brilliant moments of release (Agnes' laughter and Will's tears). In Zhao's words, "Love doesn’t die, it transforms."

9/10

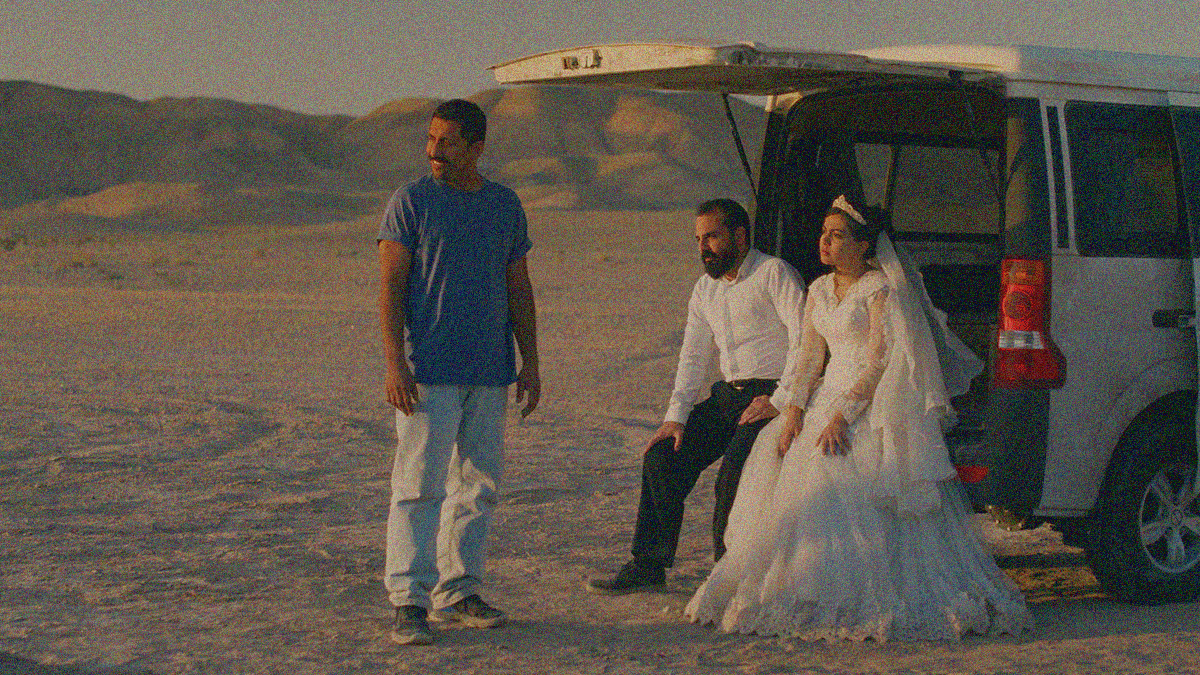

It Was Just an Accident

To have shot this movie in secret is truly the big story here. That and the Palme d'Or win. Because it's not just about hidden cameras and night scenes in the desert. It's also the long takes with a single set-up that demand Jafar Panahi's script and the actors' performances (what a great ensemble) are all impeccable.

The result is a tense and introspective morality play pitting all the different possible rationales and emotions that would arise in such a nightmarish scenario. You understand Hamid's need for revenge as clearly as Shiva's need to be better than her torturers. You recognize the difference between a sadist and someone at the end of their rope. And we consider the complexities behind the word "coward." Maybe Vahid does act before he thinks, but he does so to a fault. Quick to want to kill a man and just as quick to save another.

There's also something to be said about Panahi's choice to admit there is nuance between those submissive to a system and the system itself while also not pretending the power imbalance inherent to the latter demands that the former be seen as synonymous with it. That's why the final shot is so chilling. Regardless of Vahid's ultimate choice, the dread from hearing that squeak will never disappear.

Yes, they are all now zombies left alive to exist as broken people, but they haven't all lost their souls. They are still strong enough to do the right thing even if doing so ensures they'll be left wondering if being "weaker" might have been the smarter choice.

8/10

The Long Walk

Last I checked, Stephen King wrote The Long Walk well before both The Hunger Games and Battle Royale debuted. So, how come Quentin Tarantino doesn't have anything to say about that? Hell, Francis Lawrence surely saw the connection and grinned all the way to the bank after signing his contract.

This goes a lot harder than I expected thanks to a stellar ensemble led by David Jonsson and Cooper Hoffman (but definitely does not also end with them). I think the script fails to really hit the messaging hard enough for the ending to work beyond its abruptness and the convenient narrative connections do feel like a twenty-something author's first novel, but the introspective conversations had throughout also show the genius King was cultivating.

Sometimes it's nice to just let the mythology behind a dystopia serve as a backdrop for a tale of brotherly love that reminds us empathy and camaraderie are the truest form of rebellion against an authoritarian regime whose only hope to maintain control is by fostering a selfish individualism in its victims that asks them to subjugate themselves.

7/10

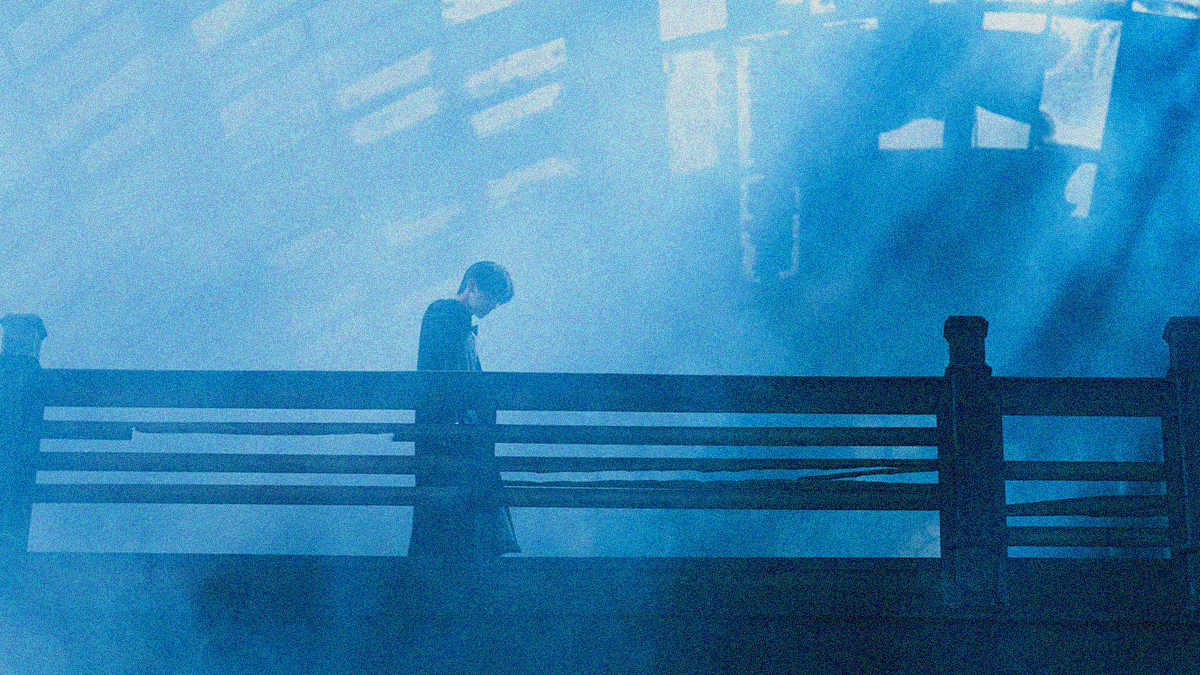

Resurrection

Would you relinquish your ability to dream if it meant you could live forever? This is what the world under the protection of a group called "Great Others" has chosen. The idea is that dreams are what burn our proverbial candles. To aspire towards something better or imagine the nightmare of something worse is to expend too much energy and wear yourself out. But isn't that part of being human? Of experiencing life? That's what a select few believe. It's why they still choose to dream and why the "Great Others" must hunt and destroy them.

Writer/director Bi Gan therefore subverts our expectations of what a monster movie is with Resurrection. In the context of our humanity, the "Great Others" should be portrayed as grotesque, authoritarian figures looking to snuff out the very concept of possibility. In the context of the world on-screen, however, it's the "Deliriants" who seek to destroy immortality's equilibrium by daring to escape reality through their minds. So, while Shu Qi initially appears to be our protagonist, she's actually out to eradicate what's left of our souls.

How do you find a dreamer? You must enter their dreams, of course. This truth leads Qi's "Great Other" into the past where her target (Jackson Yee's Monster) is hiding. Because it's not a particular great dream for the latter considering he is a prisoner forced to cry so his tears can be sold to bar patrons as a drug, his exfiltration feels almost like a rescue sans context. The fact that Qi doesn't just kill him upon capture also causes us to wonder just how dangerous he truly is. Not only does she let him keep dreaming, but she also watches from afar.

The question then arises as to whether "Great Others" have volunteered themselves for this job to preserve the status quo or to vicariously experience what they are forbidden to enjoy. By looking into one hundred years of the Monster's final dreams before death, Qi is able to see what it is that humanity lost. If you want to put a label on it, her kindness to this creature exposes her to a century of art via cinematic language and convention. Romance. Horror. Mystery. Philosophy. Longing. The sensory overload of our melting candles.

Through Qi's character, Gan treats his audience to the same. You could say it's a result of our own reality also destroying our ability to dream with new digital technologies replacing tradecraft, original thought being repackaged as content born from algorithms to increase shareholder profits, and generative AI threatening the very notion of art itself. Or perhaps it's just an excuse to travel back in time and play in the sandbox of practical effects and cinematic trickery. Either way, Resurrection proves an abridged account of film history.

Qi's search for the Monster takes us into silent era aesthetics with a German Expressionist bent as she walks through frames compositing matte surfaces with live-action movement and scenes of broken sets forming walls and windows only when the camera is set in its designated spot. More than just a glimpse of the style, though, Ban leaves the surreal artifice in to the point where we see giant hands closing windows and pulling up pieces of the set while Qi roams. And the shadow work impeccably instills a Nosferatu sense of dread.

From there it's the dreams Qi allows her captive to have. The first sees him as a film noir murderer named Qiu who wields a pen as a weapon to deafen his victims from the world's sound so they can only hear God. The next has him as a former monk turned "mongrel" who conjures the spirit of bitterness in the form of his father (Yongzhong Chen) after tasting a rock. Then it's a conman enlisting a young girl (Mucheng Guo) as his accomplice to feign "supernatural" smell. And, finally, a man in love with a woman (Gengxi Li) who he can't touch.

Yee plays the lead in every chapter and truly sets each apart in appearance, mannerism, and voice. Gan shifts genre with every progression through time—each marked by narration with the final iteration taking place in 1999 on the eve of the millennia and the uncertain future it brought to allow its characters to truly live in the present. And that last past goes one step further too as its criminal underworld riff on Before Sunrise unfolds as a one-shot long take. It's quite impressive with action, gore, and an ingenious time-lapse.

Resurrection is the best of what cinema can offer as an escape from reality and a yearning for more. It's built upon our five senses, shines a light on the magic of set design and cinematography, and wields narrative motifs in ways that harken back to their invention while also giving them new life to prove their relevancy today beyond focus groups and demographics. In an industry increasingly asking filmmakers to conform for their paycheck, Gan reminds us of what can be done with the medium when they're allowed to dream.

8/10

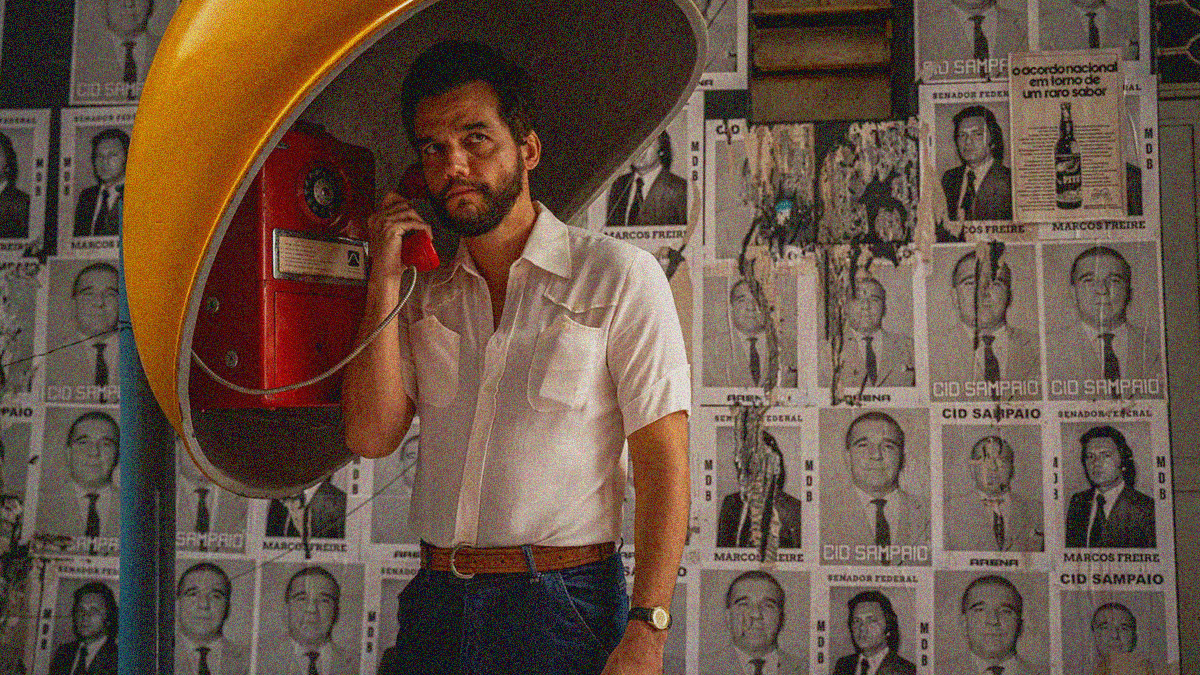

The Secret Agent

I love a title with the power to feed into how you interpret the story on-screen. Because Kleber Mendonça Filho's The Secret Agent isn't actually about a secret agent. Every synopsis reveals this truth by explaining that Marcelo (Wagner Moura) is a technology expert returning to his hometown of Recife to claim his son and flee the country. If, like me, you hadn't read a description, however, you would believe the opposite. This is a mysterious man in hiding who engages in clandestine phone calls as hitmen hunt him. Why wouldn't he be a spy?

The sole mention of the titular occupation comes via a theater screen for a period specific movie that would have been shown in Brazil circa 1977 (when audiences weren't scared out of their wits by The Omen). And since we don't learn about Marcelo's technology background until almost halfway through the run-time, why not embrace the excitement of wondering when his friendly demeanor will turn ice cold. Who will be his first victim? The hitmen (Gabriel Leone and Roney Villela)? A corrupt police chief (Robério Diógenes' Euclides)? Someone else?

These were the questions running through my head as the always calm and collected Marcelo makes his journey to Recife (those who've seen Filho's Pictures of Ghosts will recognize the city and its architecture). Here I was inferring upon his PTSD after seeing a dead body in the parking lot of a gas station (just before a police officer seemingly hopes to find contraband in his car so he can steal the vehicle for himself) and guessing at the missions keeping him from his son (and, perhaps, killed his wife), when everything is turned on its head.

This occurs by finally understanding who Marcelo is in the context of Brazil's political turmoil and from Filho throwing a wrench in the narrative by shifting us to the present day without warning. Things don't go off-the-rails crazy like in Bacurau, but there's enough uncertainty and silliness (the infamous "hairy leg") to force you to prepare for the kitchen sink. That The Secret Agent conversely proves to be a rather straightforward drama steeped in historical memory and scars might be the biggest surprise of all.

It's by no means less impactful for it, though. Marcelo and the other refugees ("We don't use that word.") living under Sebastiana's (Tânia Maria) roof are fighting for their lives in an attempt to stay out of prison or worse because of who they are. The joke is made that they've been accused of being communists and anarchists and who knows what else so often that they forget the order since the labels themselves are a mere formality for an oppressive government seeking to silence dissent. Their existence is their crime.

Filho utilizes the mystery surrounding Marcelo and the reasons why a man like Ghirotti (Luciano Chirolli) would put a bounty on his head to have fun mocking the former regime's corruption while also alluding to its danger. Yes, the "hairy leg" delivers a wild monster movie aside, but it also provides a deft entry point for both Marcelo's son (he really wants to see Jaws) and Chief Euclides. Its MacGuffin even goes so far as to help put the latter onto the same path as our hitmen—this rotting appendage guiding us through Recife's streets.

We meet friends of the resistance playing their part to stay close to the villains and gather information (Buda Lira's Anísio). There are the risk takers like Elza (Maria Fernanda Cândido) doing the work to smuggle people out and gather intel to hopefully be used to prosecute the real criminals. And don't think the late Udo Kier's brief cameo as Hans the tailor is a throwaway either. Here is a Holocaust survivor being turned into a sideshow for men who aren't smart enough to see he's made them the fools just to survive fascism again.

The supporting cast is fantastic (add Laura Lufési's Flávia to the mix as her anachronistic inclusion soon puts her centerstage in the epilogue), but this truly is Moura's show. Does his Marcelo not carry a gun because he doesn't need one? Or is it because he doesn't live a life where he ever thought he would? Just as Brazil seeks to slander him as a radical and violent man, the film fantasizes about proving his heroism via genre conventions because it knows a good man caught within a corrupt machine isn't as sexy as a covert operative on the lam.

Once again, though, Filho never says that's what he is. He doesn't outright trick us into believing a lie. He merely draws Moura into situations that can be construed as such without the proper context to see otherwise. It's a brilliant bit of implicit manipulation that ensures engagement in such a way that we don't get angry once the strings are revealed. We become impressed. Not only that, but we find ourselves so invested in Marcelo's safety that we never stop seeing him through that lens. Because speaking truth to power is just as heroic.

8/10

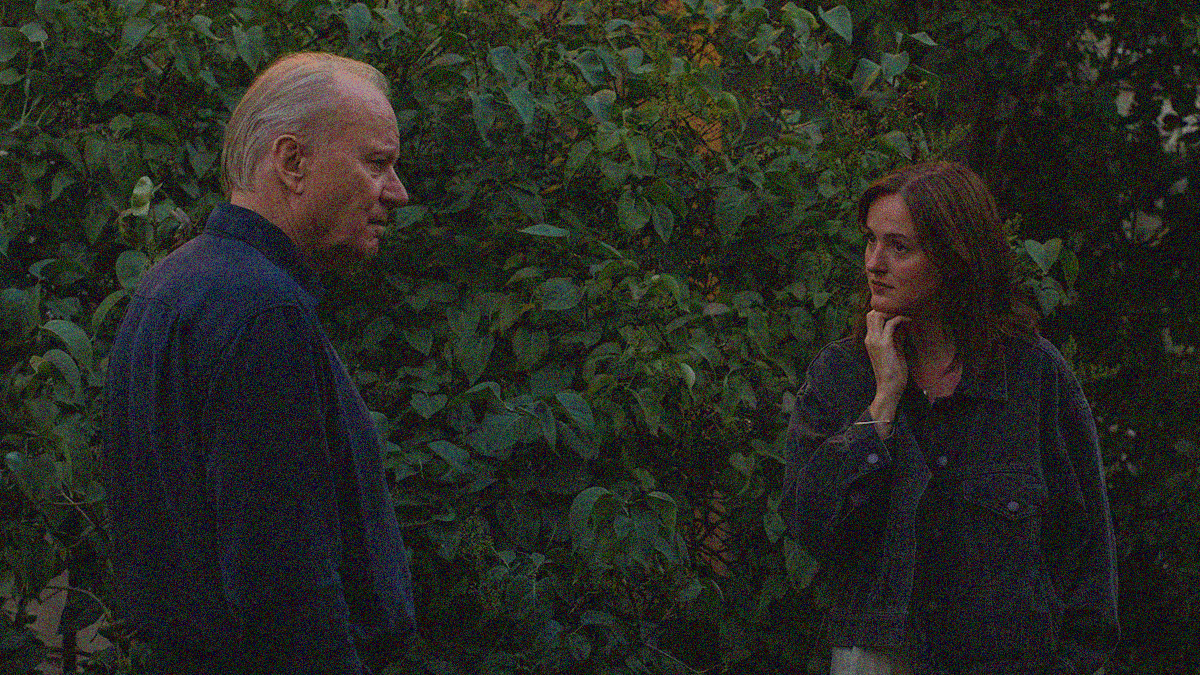

Sentimental Value

I was very worried towards the end of Sentimental Value. Gustav's (Stellan Skarsgård) latest, highly personal film started falling apart in ways that made its continuation seemingly impossible to drive home the point that it wasn't his age or that of those he wanted to collaborate with that was derailing his vision. It was him. His choices. His neglect. I loved the message behind this realization and reveled in the fact Gustav might actually learn he's too late to be redeemed when director Joachim Trier and co-writer Eskil Vogt tease the opposite.

The transformative power of art does heal wounds and repair relationships. It helps people figure out the cause of their pain and better process a way forward. See Chloé Zhao's Hamnet for another example of exactly that. But it's tough to accept that truth when it's presented via a character who hasn't earned it. Yes, Gustav's choice to be an artist first and father last (not even second) affected him as much as his daughters, but the distance he put between them isn't his to erase. Not after so many years. Not after they built their lives without him.

Thankfully, Trier and Vogt don't fall prey to that impulse. Not only would it have felt disingenuous in the moment, it also would have been contrary to the whole considering the script's three-headed story mainly focuses on Gustav's eldest Nora (Renate Reinsve). To have him or her sister Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) somehow cajole her into believing he'd changed despite her struggle to exist outside the shadow of his absence would have undercut her despair. They needed it to be a springboard towards closure rather than healing.

I think they pulled it off. The ending is perhaps a bit rushed considering the room they gave everything else leading up to it, but the remodeling work of the Borg family's home perfectly expresses the remodeling work Nora and Agnes must undergo to both accept their father's place in their lives and find the strength necessary to ensure he realizes that acceptance is on their terms rather than his. That's the real evolution that's undertaken here. What used to be about wanting their dad has now become about him needing them.

Agnes calling her father's screenplay "overwritten but impactful" is funny since I'd use the same description for Sentimental Value. The film often lingers on moments of epiphany—generally the result of an outsider (Elle Fanning's actress Rachel Kemp) giving her objective read on what's too personal to the others—as if they should shock to us as much as them despite Trier and Vogt doing well to ensure the reverse. We get what's happening from the start. The question is whether Gustav and Nora will be vulnerable enough to talk about it.

In great cinematic fashion, however, that "talk" manifests in a much less literal way. It comes from Nora and Agnes talking about something alluded to early on but never confirmed until later. It comes from a silent look of respect by Nora and Gustav rather than the previous yearning to be loved. This family has suffered for generations, and the resulting anguish lingers in their bones (and the house's) regardless of their ability to acknowledge as much. It's rare that a film with this subject matter recognizes the cleansing nature of a fresh start.

Hence the title—found in a line of dialogue spoken by Agnes when organizing the objects left behind in their childhood home now that their mother has died (and where their father hopes to shoot his new film). She talks about everything having sentimental value and how Nora should want to keep something when it's probably healthier to not. Why trap yourself with the emotions and memories of a time that hurt as much as her childhood? Because it's not a trap for Agnes. Their circumstances were the same, but their experiences weren't.

Reinsve and Lilleaas are constantly revealing this truth through their characters and performances. Nora's perpetual state of anxiety causing her to self-sabotage. Agnes' perpetual state of worrying in order to protect those she loves. I know we need to spend as much time with Gustav (Skarsgård is equally heartbreaking and narcissistic) as we do because it's his flash of inspiration that ignites the potential for his daughters to let go of his hold upon them, but the film is never better than when those two women are on-screen together.

The film deserves the critical acclaim, but I do feel like it's a bit too perfect and obvious when compared to Trier's other work. It's still legitimately great and that final scene between Reinsve and Lilleaas is worth the price of admission alone, but it kept me at an arm's length for a good portion. The infinite abrupt cuts to black didn't help by forever jarring me out of the moment, but the hilarious choice for Gustav to give his eight-year-old grandson Irreversible and The Piano Teacher as birthday gifts proves an even trade.

8/10

Opening Buffalo-area theaters 12/12/25 -

• Akhanda 2 - Thaandavam at Regal Elmwood, Galleria

• Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas (25th Anniversary) at Dipson Flix, Capitol; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Dust Bunny at Regal Transit, Quaker

Thoughts are above.

• Ella McCay at Dipson Amherst, Flix, Capitol; AMC Maple Ridge, Market Arcade; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Mowgli at Regal Elmwood

• Not Without Hope at Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Rolling Stones - At the Max at Regal Transit (weekend only)

• Sentimental Value at North Park Theatre

Thoughts are above.

• Silent Night, Deadly Night at Dipson Capitol; Regal Elmwood, Transit, Galleria, Quaker

• Vaa Vaathiyaar at Regal Elmwood

Streaming from 12/12/25 -

• Dímelo bajito (Prime) - 12/12

• F1 (AppleTV+) - 12/12

Quick thoughts at jaredmobarak.com.

• Influencers (Shudder) - 12/12

• Spinal Tap II: The End Continues (HBO Max) - 12/12

• The Mastermind (MUBI) - 12/12

"Reichardt writes the theft as a humorous series of missteps and inconveniences. O’Connor nails the hangdog expression of finding himself thrust into taking a hands-on approach to what he believed would be very hands-off." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• Wake Up Dead Man (Netflix) - 12/12

• Eye for an Eye (Starz) - 12/15

• Megadoc (Criterion Channel) - 12/16

• Murder in Monaco (Netflix) - 12/17

• 10DANCE (Netflix) - 12/18

• Counting Crows: Have You Seen Me Lately? (HBO Max) - 12/18

Now on VOD/Digital HD -

• The Carpenter's Son (12/9)

• Christy (12/9)

"Thankfully, the energy supplied by the acting is high enough to push through and appreciate the lessons and the woman behind the bludgeoning we’re receiving on behalf of the plot." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• Chainsaw Man - The Movie: Reze Arc (12/9)

• Die My Love (12/9)

"I love that the film positions Grace as the model of sanity rather than the person who needs fixing. Because parenthood is crazy and sacrificing your identity for love isn’t tenable." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• Dogma (first time on digital) (12/9)

My thoughts from 2014 at jaredmobarak.com.

• Israel Palestine on Swedish TV 1958-1989 (12/9)

• Keeper (12/9)

• Köln 75 (12/9)

"Fluk infuses an energy that makes veracity an afterthought to entertainment. Köln 75 is instead about vibes, jazz, and the woman who made The Köln Concert iconic despite the guy who happened to be playing the music on-stage." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• Little Amélie or the Character of Rain (12/9)

"The film’s animation style suits this truth too with its impressionistic color fields creating dimensionality rather than relying upon outlines. It lets the real and surreal overlap so the drama is always filtered through this child’s eyes." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• A Savage Art (12/9)

• Stop the Insanity: Finding Susan Powter (12/9)

• Corey Feldman vs. the World (12/11)

• Lone Samurai (12/12)

• The Mastermind (12/12)

"Reichardt writes the theft as a humorous series of missteps and inconveniences. O’Connor nails the hangdog expression of finding himself thrust into taking a hands-on approach to what he believed would be very hands-off." – Full thoughts at HHYS.

• One More Shot (12/12)

• Thieves Highway (12/12)

• Turbulence (12/12)

Pieces from the Ordinary People (1980) press kit.